RWMMost people know that New Mexico officially became a territory of the United States in 1850, and a state in 1912. However, we must keep in mind that this magazine is published on the Internet and reaches people far away from here this country. Also, as our state magazine attests to every month, there are still some in our own country who do not know where to find New Mexico, who don’t realize New Mexico is very much a part of the continental U.S.A. A portion of the following article deals with U.S. citizens, residents of New Mexico, who were in a dreadful accident in Mexico, where they were treated very badly by Mexican Nationals. Roswell Web Magazine wants to be assured that all readers know the difference between the two — New Mexico and Mexico — when they read this article.

MARY FRANCES LAUMBACH

RWM

Mary Frances Laumbach won’t let anything totally derail her from achieving her goals — not even dreadful personal experiences, crippling physical pain and heartbreak that would wreck almost anyone else. At the youthful age of 34, Frances has experienced more trauma than most people experience in their entire lives.

Among her personal attributes are her amazing inner strength and resiliency and her determination that nothing keeps her from reaching her goals. She was physically and emotionally wrecked a while, but not forever.

One of her goals had been to earn her Master’s degree in guidance and counseling. Although she was briefly knocked off-track from that, she officially received her Master’s degree a few weeks ago, on May 4. Now, her goal is to get her doctorate.

Another goal is to help kids. That one has no defining perimeters, no beginning and no end. Working with youth and helping them feel good about themselves, achieve their own goals and lead productive lives is what she will always do. That is a large part of who she is. Working with youth and young adults — especially those disadvantaged or at-risk — is Frances’ primary function. She — who has had plenty of her own woes — listens attentively to theirs and gives them the inner strength and tools with which to help themselves.

Mary Frances Laumbach wears two hats: military — as captain currently assigned as S4 Logistics Officer in the U.S. Army National Guard, and civilian — as a student counselor.

Military:

Mary Frances Laumbach graduated from Springer High School in 1986, and went to NM Highlands University on an athletic scholarship — volleyball and basketball. She joined the Army National Guard in May 1988. She immediately went to basic training and then to Advanced Individual Training (AIT). She contracted with Highland’s Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) and July 1990, she received her Army officer commission, along with her bachelor degree in clinical psychology, at HU. She went on active duty, special work, for two years, assigned to Directorate of Plans and Training and recruiting for Officer Candidate School (OCS) across the state of New Mexico. She was assigned as a full-time TAC officer, training National Guardsmen at the WET (Weekend Training) Site near Bottomless Lakes east of Roswell. When the WET Site was relocated to Santa Fe, she transferred to Roswell’s First Battalion, 200 Air Defense Artillery. After that transferal, she was assigned as acting Headquarters Battery Commander at the first annual training. Since then, she had been assigned as 320th Ordnance Detachment Commander, Communications Office, S1 Personnel Officer, as Headquarters Battery Commander, and then, after her accident, as Logistics officer. During the recent annual training, she was again assigned as acting Headquarters Battery Commander.

After her disabling auto accident, when everyone believed she would never walk again, she gave up her command position, but eventually returned to being active with National Guard. She was recently offered a command post in Rio Rancho, but reluctantly turned it down because she will soon move from New Mexico to southern Colorado. Although she loves Roswell, her job and deeply appreciates the support of her family, friends and colleagues through good times and very bad ones, these past two years have been difficult. “I need to be closer to my family,” she said.

Student Counselor:

Professionally, Frances has worked with youth and students — at the juvenile correction center, in grade school, middle school, and with teenage cadets — for 10 years. She stresses to them the Character Counts of Chaves County’s six pillars of character: respect, trustworthiness, responsibility, fairness, caring and citizenship. These positive traits are woven into everything she teaches. In addition, she works to build students’ self-esteem, and teaches them basic life skills and self-reliance. She teaches life-coping skills, anger management and relaxation techniques, conflict resolution or mediation, prejudice and discrimination prevention, drug and gang prevention. To older students, she also teaches time management, financial responsibility and employability skills, how to dream positively and then all of the practical steps required to achieve those dreams. She arranged school-wide activities, many of which included guest presenters.

She began to work in her chosen field in 1992 when she was hired as counselor at Roswell’s Nancy Lopez Elementary where she worked for seven years. “I’ve had many challenging cases in the past 10 years as a student counselor,” she said. “I began without any experience. I grew up in the little community of Springer where I saw no abuse, neglect or gangs.”

When she began at Nancy Lopez, there was no prior counseling program, no built-in format or curriculum to inherit. She designed and created an extensive and comprehensive counseling program that included monthly classroom presentations and school-wide needs assessments involving staff, parents, students and members of the community.

She said her methods have always been reality-based, and she illustrates consequences of bad behavior and choices. “Bang Bang You’re Dead” is a fast-paced, difficult yet rewarding student play that she has directed for several years.

As a good Character incentive, she initiated “Catch a student doing good.” The names of students, observed by teachers and staff “doing good” were put into drawings for big prizes, including bicycles — that, in turn, required fund-raising events.

During Red Ribbon Drug Free Day, more than 400 elementary students, “armed” with red balloons, went on a Drug-Free Walk of 2.8 miles with the Roswell Police’s School Resource Officer, Bert Flores. For another event, students brought cardboard boxes on which they wrote all the things they wanted to symbolically destroy — drugs, abuse, anger, gangs — which they burned in a bonfire. Another event culminated in job shadowing professionals. First, the children’s aptitudes were inventoried, and then, based upon results, each was given a career placement for a day. Some “shadowed” Municipal Judge Hector Pineda in court and were given the opportunity to participate in court judgments. Others spent the day elsewhere, including at the Roswell Fire Department, with attorneys, a veterinarian, and Aladdin Cosmetology.

Laumbach implemented parenting classes. Parent support groups showed moms and dads ways to have better parent-child relationships and how to boost their children’s self-esteem.

“Unlike an electrician who does the same thing each day, every day for a counselor is a new, different experience,” she said. When she observed evidence of neglect or abuse, she made a referral to Social Services. When she did, parents often directed their anger towards her.

She was offered a counseling position at higher pay at Mesa Middle School. It was during spring break, towards the end of her first year at Mesa, that her life-shattering accident in Mexico occurred on March 24, 2000, interrupting her counseling career and National Guard advancement. Frances’s daughter was killed, and she, her other child and young friend were critically injured. Following hospitalization and multiple surgeries, she went into a period of convalescent isolation, for physical and emotional healing.

The next fall, she returned to Roswell and her counseling job at Mesa Middle School. Because of her accident and its lingering physical effects, she gave up her National Guard command position, but she again become actively involved with National Guard.

After almost two years at Mesa, last year Laumbach received another counseling job offer, no doubt because of her strong Army National Guard role, success as a student counselor, and Master’s degree in that field. This time, it was as counselor for New Mexico Youth ChalleNGe Academy, at a considerable increase in pay. Each prior job was important to her, but each new one was a professional advancement.

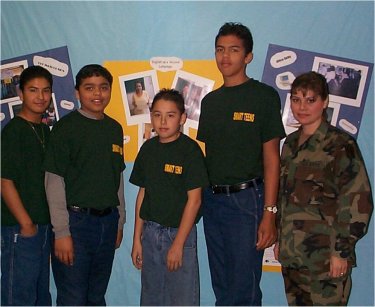

NMYCA began May 2001 at Roswell. It is a 22-week course for at-risk youth — boys and girls between the ages of 16 and 18 who dropped out of school. There are several others in the U.S. but the one at the DeBremmond Training Center at Roswell’s Industrial Air Center is the only one of its kind in New Mexico. The program, run by the National Guard (the reason for the capitalized NG in the name), is similar to military boot camp. Cadets require supervision 24/7. Cadets, who voluntarily choose this program, are taught strict military-type discipline and wear military garb. NMYCA teaches academics to prepare cadets for their GED exam, and also self-esteem and life-skills. That’s where Laumbach comes in.

Following the program, each cadet is given three choices: employment, further education or military service. Capt. Laumbach stresses the importance of active military duty or advanced education. “Without one or both of those, employment pay will likely afford you little more than your basic needs,” she tells cadets.

She employs all of the programs and techniques that she used at Nancy Lopez and Mesa, including the importance of good character traits, plus many others. One of those is career collages that depict their futures, followed with their written bios. Each cadet is encouraged to positively see his future life, by — with magazines, scissors, glue and poster-board — making a collage depicting all of its aspects. A collage might have a picture of a nice home, a luxury car, a family and a professionally dressed person (symbolizing the cadet 10 years from now). The cadet then writes his future biography — his chosen achievements and everything, step by step, that he must do to achieve them.

Laumbach is proud that four NMYCA cadets she worked with have graduated from Army or Navy basic training. Cadets come to Roswell for this program from all over New Mexico, and many keep in touch with her when they return home or take the next steps into their futures.

Frances Laumbach had been divorced from Nick Coca, Miranda’s father, of Las Vegas, since Miranda was a small child. Frances and Miguel Vasquez, along with Miranda and Marina, Miguel’s daughter, lived together in Roswell.

After everyone was in the car and they were ready to pull out of the driveway for a trip, Miranda said she had to run back into the house to do something she forgot to do. She insisted, and her family waited for her to do whatever she thought she had to do. Much later, they discovered what that was. Inexplicably, Miranda took her special ring off her finger and left it in the house. (Her mother now wears it constantly.) And she changed the family’s telephone answer machine recording, which had been unchanged for four years. “Hello, we can’t come to the phone right now … we’re gone on a trip,” she recorded that night, and that is what her voice still says to anyone calling the house.

March 24, 2000, Frances was traveling in the country of Mexico (south of New Mexico’s state border) with her two daughters, Miranda, 10, and Marina, 4, and Miranda’s good friend, Justine Ledesma, 11. With them also were Miguel and his 13-year old brother. Miguel was driving. Dental repairs for Frances at lower cost than in the U.S. was the purpose of the trip to Cuahutemoc, Mexico, where Miquel once lived. Ultimately, the cost of the trip was beyond anyone’s imagination.

They had begun their trip the evening before and traveled through the night. The passengers were sleeping; Miguel said he must have dozed off about 7:30 a.m. the next morning, causing the single-auto accident, 40 miles north of Chihuahua, Mexico. The car rolled several times.

The children were thrown from the vehicle. In spite of her own terrible injuries, Frances got out of the totaled car and walked to where the children lay crumpled on the roadside. She saw Miranda had a bad gash in the side of her head.

Marina had punctured lungs, broken clavicle and severe head injuries. Justine had a broken clavicle. Frances had multiple broken vertebrae in her neck and back, and a shattered wrist. Only Miguel and his brother were relatively uninjured.

Two college students from El Paso, Texas, visiting in Mexico, witnessed the accident. They began driving Frances and Miranda — in the back seat of their small car — toward Chihuahua for medical help until they were intercepted by an ambulance that took them, in separate ambulances, the rest of the way to Chihuahua. When they were put into the ambulances was the last time France saw Miranda, and she was still breathing. Occupants of a Bronco soon also at the accident scene began transporting the rest of the accident victims, until they too were met by ambulances that took them the rest of the way to the CIMA Hospital in Chihuahua.

There, the bones in Frances’ hand were set (but badly done, requiring reconstruction in a U.S. hospital). X-rays were taken of her back and neck clearly showing the broken vertebrae, but they were ignored and CIMA personnel carelessly moved her about. CIMA operated on Justine (which was totally unnecessary) and inserted a pin, narrowly missing her heart and causing paralysis. (Justine remained paralyzed until the pin was removed in a U.S. hospital.) Marina was not breathing and CIMA put her on a life-support system. Frances learned Miranda died.

She desperately tried to call her family, but for hours, CIMA personnel refused to let her use a telephone. At last, she reached her 14 year old niece, Vanessa, who was the first to receive the dreadful news and relay it to Frances’ parents, Leo and Helen Laumbach, in Springer. First, they had to go to the Colfax County seat in Raton to obtain birth certificates. Leo and Helen arrived in Chihuahua the next day, as did Justine’s parents.

The responsibility of identifying Miranda’s body fell upon Leo and Helen. They definitely identified her, although she was at a homicidal facility and the autopsy was completed. They noticed a deep gash in the side of her head. They were told Miranda’s body would be taken to a mortuary. They rushed to buy clothing for Miranda and then went to the mortuary — named Funerales de Miranda — which left them breathless. The mortuary took a great deal of information from them but, no matter how hard the grandparents tried to see her, the hospital refused to let them see Miranda. “Oh no, you don’t want to see her with the terrible damage to her face,” they were told. Reconstruction of her face would take many hours, they were told. What facial damage? thought Frances’ parents; they had seen none, only the gash in the side of her head. They never saw Miranda again after they had identified her.

Mexican authorities threatened Miguel, the driver of the vehicle, with a charge of vehicular homicide and lifetime Mexican imprisonment. A lawyer hired by his family warned him to leave quickly. He managed to leave the hospital and return to the U.S. on his own. Although Mexico is his home country, he cannot return without fear of being picked up on an arrest warrant.

All of the Americans — the patients as well as their families who went to Chihuahua to help them — were treated badly by CIMA Hospital personnel. Obtaining the release and return to the U.S.A. of the critically injured patients and Miranda’s body were almost insurmountable tasks, and could have become an international incident.

CIMA Hospital was American-built with American dollars, but run by Mexican Nationals. They would not accept Frances’ New Mexico teachers’ insurance coverage, Blue Cross-Blue Shield, that is internationally accepted. The hospital also would not accept payment of the medical bills by credit card. The only thing they deemed acceptable was cash. At first, “the price on their heads” was $4,000, which happened to be the amount of cash Frances had with her to pay for her dental work. But the price crept upwards. The hospital would not release anyone until all of the hospital bills, ever increasing, were paid in full.

The New Mexico Army National Guard tried to work for their release behind the scenes, and a Met Life jet, chartered by Blue Cross-Blue Shield, was sent to Chihuahua to fly the patients to the University of New Mexico Hospital in Albuquerque. Still the hospital would not release them, even while the jet sat on the Mexican airport runway. In effect, the critically injured patients were held hostage for the growing amount of money, in cash, demanded by the hospital. Frances’ father, Leo, offered himself as collateral if they would let his critically injured daughter, granddaughter and her young friend go. Both the hospital and the airport benefited by the delays. Besides at the hospital, costs climbed at the airport while the jet sat on the runway at a cost of $1,000 an hour. Ultimately, the Chihuahua airport charged the jet a fee of around $11,000.

At last, when the family was able to produce $11,000 cash applicable to the hospital bills, the most critically injured patient, Marina, was allowed to leave. Her life depended upon it, but CIMA would not allow the life-support system to go with her, not even a few hours. Marina’s grandmother, Helen, traveled with her by taxi and it was a long, harrowing ride from the hospital to the distant airport and the medically equipped U.S. jet. The stress of the journey was further increased by waiting at a railroad crossing for a long train to pass by. Helen prayed the whole way. Marina had stopped breathing by the time they arrived at the jet and she was put back onto life support.

“She was brought back from death to life,” said Frances. “She is truly a miracle child.” The jet got her to Albuquerque in one hour.

CIMA continued to hold Justine and Frances for the balance of the money — ultimately a total of $19,600 cash. Later scrutiny of the medical bills showed that some of what was itemized was not pertinent to them. “Someone else’s bills were tacked on,” said Frances. Leo and the Ledesmas, Justine’s mom and dad, were held under security at the hospital. The three had to stay together in one small hospital room and bathroom. Leo later said they could not even go to the bathroom without an attending guard present, and all phone calls were monitored.

Throughout this ordeal, which must have seemed like forever for the seriously injured patients and their families, cash was hastily gathered back in New Mexico, U.S.A. The communities of Roy, Springer, Las Vegas and Roswell, and other sympathetic and outraged groups and individuals, scrambled to gather enough donated cash to pay for Frances’, Marina’s, Justine’s, and later Leo’s and the Ledesmas’, release from Mexico.

Finally, after receiving $11,000 cash, CIMA agreed to release Frances and Justine, keeping Leo and Justine’s parents hostage for the balance. Like Marina, they were flown by jet to the UNM hospital where they were immediately admitted to the trauma unit. When Frances and Justine arrived at the hospital, Frances was later told by staff and others, the facility was swamped by many concerned people and news media, as if she were a celebrity. “We’ve never had a patient receive this much attention and support,” she was told. The news of their bad treatment in Mexico and their plight had been broadcast across the state and far beyond.

Frances’ mother and father arranged for transport of Miranda’s body to Las Vegas, NM for service and burial. After CIMA received the full amount demanded, Leo and Justine’s parents were able to return to New Mexico in time for Miranda’s funeral.

(photo taken 3 days before her death)

A man named Nestor who lived in Chihuahua had once attended school in Springer and knew Helen. He heard of her family’s dilemma and went to the hospital to try to help and he stayed with them. It was he who drove Leo and Justine’s parents back to the U.S. when they were finally freed.

Despite her fragile condition, Frances traveled from Albuquerque to Las Vegas to attend her daughter’s service. Col. Jimmy Gomez made arrangements with TV Channel 13 to fly Frances in their helicopter, but the weather was too stormy. Instead, SFC. Kathleen Gonzales from 111th Air Defense Artillery Brigade drove her in her van the approximate 110 miles from Albuquerque to Las Vegas. Frances traveled with a wheelchair, in neck and back brace, and arm in a protective sling with her right hand having been surgically reconstructed the night before. Along with many others, a large contingent of New Mexico Army National Guard attended the service.

In the church, Sgt. Major Ronnie Kilgore pushed Frances in her wheelchair to Miranda’s casket so she could view her daughter. The child lying there, with a badly injured face, was an older girl. The child sent from Mexico for burial in Las Vegas was not Miranda. After her first terrible cry of shock, Frances said nothing about it. What could she do? It was a helpless situation, and she was afraid people would think she was crazy. During the burial, the wind drove freezing wet snow horizontally through people’s clothing. Her family stood exposed to the elements holding coats and blankets behind Frances’ back trying to protect her from the storm. Immediately after the burial, Frances was returned and readmitted to the UNM Hospital, where she underwent additional surgeries. Frances wore a neck-brace until May 8, 2000 when she had neck surgery and a metal plate was inserted.

Frances and Marina were eventually released from the hospital and taken to Springer to be with their family for a long physical and emotional convalescence. Frances spent 80 days in self-imposed isolation at her parents’ home, deeply disturbed by the tragedy and related events.

Finally, Frances had a dream in which she was told that she had many unfinished things yet to accomplish. She had begun working towards a Master’s degree and had been working with troubled children; she had completed neither goal. She got out of bed and returned to her life.

That was almost two years ago and she has been up and running ever since. She continues as a youth counselor — at Mesa Middle School the first year after her accident, the next year with Youth Challenge. She was again acting Headquarters Battery Commander at the National Guard annual training in early May and, also in May, she acquired her Master’s degree.

Frances was recently — February 23, 2002 — in another accident. She and her family were in her sister’s Suburban. With her were: her daughter, Marina; her child’s friend, Justine; her mother, Helen; her sister, Raylene; and Raylene’s four children. They were traveling on I-25, between Pueblo and Trinidad, Colorado. Frances was driving. Clearly visible ahead was an automobile accident, with emergency vehicles already at the scene. A Colorado State Police officer stood in the highway slowing or stopping traffic. As Frances approached, she slowed the vehicle. She heard someone shout, “Get out of the way!” and just as she began to veer to the right and saw the officer dive for the bar-ditch, their car was struck in the rear by a speeding vehicle.

It was deja-vu for nearly everyone in the car. Mary Frances was injured by whiplash before her neck and back had recovered from her first accident. Everyone in the vehicle received whiplash and ligament damage and continue to receive medical treatment. This accident renewed the trauma of the first one, especially for Marina, Mary Frances and Justine. This time, the accident victims did not have to wait for transport to medical care because ambulances were already at the scene.

“If that car hadn’t hit us, it would have killed that officer,” said Frances. “I’m glad no one died.”

Frances had serious side-effects from this second accident. She missed three weeks before returning to work, but she still suffers. She takes painkillers and uses a TENS device at night to electronically block some of her pain so she can sleep.

One of her coping techniques is to be constantly busy and surround herself with young people. She said helping kids is one of the ways she takes her mind off herself.

It will be Roswell’s and New Mexico’s loss when Capt. Mary Frances Laumbach moves to Trinidad, Colorado in August, but none who love her doubt her need to be closer to her family. Her sister, Raylene, lives in Trinidad, and her parents will be only 60 miles away.

Mary Frances Laumbach said she will be eternally grateful to her parents and all of her family, friends, colleagues, and even strangers she will never meet, who were supportive with their love, prayers, time and financial assistance when they desperately needed it.

“Without them I would not be here,” she said.

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine