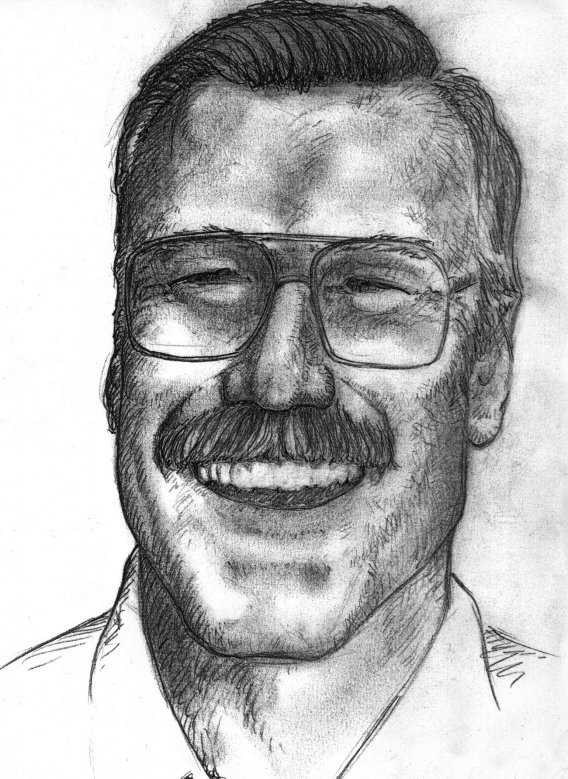

Known as a bear of a man with the heart of a lamb, Roswell Fire Chief Steven Louis Jones was greatly admired by his peers and beloved by the community and state he served and helped to protect.

He was an humble man, unconcerned with himself, but a fiercely protective, loyal and able leader of his firefighters and fellow emergency personnel.

His larger-than-life size and physique made him seem like Superman, powerful enough to catch and deflect a speeding bullet. It didn’t seem possible that anything, not even a bullet, could stop him, but it did, in the early morning hours of March 16. He died 10 days later.

At his service, many hundreds of firefighters, law enforcement officers and emergency personnel came from near and far to honor him. Fire trucks of ever size, type and color filled downtown Roswell’s streets and parking lots for many blocks surrounding the church where his services were held, and the funeral procession, seemingly unending, extended with lights flashing from the middle of town all the way to the cemetery.

It was my privilege to interview Jones on several occasions. The last time I saw him, within six weeks of his death, he was moving furniture and cleaning an office at Station One, which had undergone renovations. To stay within their lean budget, the chief and his firefighters were always doing as much as possible themselves.

When he was promoted to Fire Chief in early April of last year, I interviewed him. From his desk, he looked up at me from between his fingers, saying “This is embarrassing.” He did not want to talk about himself, but he was very comfortable speaking of Roswell’s firefighters and how important they and all emergency personnel are to their respective communities. I continually pulled him back to himself, a subject he preferred to avoid. Much of my information about Jones’ RFD advancement was taken from a copy of his resume that he gave me.

While I sat in his office after his promotion to Chief, a florist made a delivery to him. He looked at the card and smiled. “From my lovely wife, Carol,” he said.

Whenever I interviewed him, he commented on “my beautiful wife, Carol,” and assured that I mentioned her in my notes. Carol Jones is a firefighter in Fort Worth, Texas. Last April, she had been named Firefighter of the Year by that department for her actions during a tornado, and he talked about that. Chief Jones was very proud of his wife.

Jones’ son, Marty, is a Chaves County Sheriff’s Deputy, and his son, Cody, works at Albertson’s in Roswell. His daughter, Christie, lives in Arkansas. All three of his children are married. His parents and two of his three brothers reside in Roswell.

Jones said he was born in Oklahoma, but his family moved to the Roswell area when he was about five years old. He grew up on a ranch 25 miles east of Roswell.

“For its size, it should have had three or four ranch hands, but the work was done by Dad, mostly. My three brothers and I helped out when we could.” Jones credited his own strong work ethics to his dad and his years of living and working on the ranch. “You work without supervision, you have to be honest and do your job,” he said. His elementary education was at “the old LFD” school, he attended Berrendo Middle School, and graduated from Roswell High School in 1974. Because of ranch life, he was on the bus by 6 a.m. and off at 5 p.m. each school day. He attended Texas’ Sul Ross State University. For a while, he returned to ranching. He was a ranch foreman in Oklahoma and on ranches near Roswell.

He was hired as an RFD firefighter in August, 1982. He took his initial recruitment schooling, which then was an intensive and informative three weeks of training. Now, he said, that initial training is an eight-week program.

That was only the beginning of Jones’ training and classes he took, many of which were elective. He showed an unusual amount of interest in and commitment to his job. Classes included emergency medical technician training. Within his first two years with the RFD, he became an EMT basic instructor and coordinator.

March 1983, he was promoted to driver, a step towards becoming an RFD officer, and he began riding rescue. In July 1984, he applied to attend state fire training academy but instead, he was asked to be a training instructor in building construction and forceable entry. The next year, he was again asked to instruct.

April 1986, Jones was promoted to Lieutenant. He reworked the drivers tests to make them more realistic to actual situations firefighters face. He also reworked the tests for firefighter applicants, making them more comprehensive and reflecting the full depth of knowledge required of the apparatus and equipment.

He worked as roving lieutenant and filled in as battalion chief. He said a battalion chief, the same as a shift commander, is responsible for all of the Roswell fire stations during his duty hours, as well as for the 21 pieces of apparatus and 25 shift personnel. After Jones transferred to Station One, he filled in for battalion chief, became acting battalion fire chief, and was promoted to battalion chief August 1991.

When I interviewed him April 12, 2001, he said the number of apparatus and personnel were the same as they had been 10 years earlier. Yet, he said, the number of calls to which they respond have more than doubled.

He said the number of fires they respond to were considerably reduced because of preventative measures firefighters take and teach. Medical and trauma calls account for the increase of the number of calls, about 80% to 85%, to which they now respond.

In 1984, the RFD began to respond to all medical calls within Roswell and then expanded their response area into the county. Besides their designated rescue wagons, all of their trucks began to be equipped, and have trained personnel onboard, to respond to emergency medical and trauma calls.

Because of their strategically placed stations around Roswell and the RIAC, they have the fastest response time of any emergency units. A few days after the incident that ultimately took the Chief’s life, City Councilor Judy Stubbs said Jones had commented that he hoped the city’s embattled ambulance service would be able to come under the jurisdiction of the RFD.

Since my interview of Jones a year ago when he became chief, two new fire stations have been dedicated, the remodeling of all other stations is in process, and the RFD has purchased six additional apparatus (which, to the unenlightened, are units or trucks). It is standard procedure that each fire truck is custom-built to specifications. The manufacture of the RFD’s six new ones is in process.

Through several prior chiefs’ administrations, the RFD has needed additional firefighters. Jones asked the City to appropriate funds to hire six more, stressing that firefighters are at risk when their crews are understaffed. After years of being chronically understaffed, thanks to the chief’s efforts, the City recently allocated funds to hire the six additional firefighters the department needed.

Last year, Jones and the RFD brought before the City of Roswell and the County of Chaves a proposal for a grant for a burn building training center for firefighters, a facility that could also be utilized by fire departments from all over the surrounding area, as well as law enforcement officers. RFD Lt. Shane Adams drew the professionally detailed blueprint. Both the county and the city have allocated land for the center, and the RFD, comparing the assets at both locations, will select one of those. Funds have now been allocated to provide a water system to the site that is chosen. Those are the first steps towards bringing the center, Jones’ dream, to reality.

Roswell Fire Department personnel credit Jones with many improvements and advancements in the short period of time, just under one year, that he was their chief. He was eligible to retire in August but it is doubtful retirement was in his plans.

Residents have asked why the city’s fire chief was at the scene that dark night, in the early morning hours of March 16. Some law enforcement personnel said he randomly showed up at fires, reflective of the type of good and responsible chief that he was. Some firefighters said he heard on the scanner that there was an explosion along with a fire, and their chief responded out of concern for his firefighters.

Quickly at the scene, Chief Jones saw injured people and did not hesitate to try to render them aid.

No one would have expected a firefighter, much less the department’s chief, to be shot in the line of duty. “Killed by a building caving in on our heads, yes, we can expect that,” said a firefighter collecting donations the next weekend for all March 16 victims’ families. “But not by a bullet.”

When I had interviewed Chief Jones after “nine-one-one” (the national emergency of September 11), he reminded me that many firefighters die in the U.S. every year; it is a dangerous livelihood. The large number of firefighters who died in Manhattan at “Ground Zero” would further increase the number of fatalities for the year 2001, he said.

The “nine-one-one” national emergency and tragedy in New York belatedly brought to the nation’s conscience recognition to and appreciation of firefighters. Since Sept. 11, the image of a man with soot-smudged face, wearing a brimmed helmet, yellow slicker and high-topped boots, evokes a hero. But “sung” or not, firemen have always been heroes.

When I had interviewed him on September 11, 2001, Chief Louis Jones had said, “We never know what to expect when we respond to emergencies, but responding to emergencies without thought for ourselves is what firefighters do.”

Steve Lovato was a member of American Medical Response’s emergency crew dispatched to a reported fire and explosion in south Roswell in the early morning hours of March 16.

Lovato was one of the good guys who regularly respond, without hesitation, without fully knowing the situation to which they are called, where someone might be ill, injured or otherwise be in crisis.

It was a structure fire. A badly burned person had run out of the flaming dwelling and crossed the street to a neighbor’s house. EMT Lovato crossed the street to render aid to the burn victim and to other victims he saw there lying on the ground. Lovato was shot and died instantly.

Steven Lovato, 30, had a 10-year old son. His wife, son and parents live in Roswell.

Five were shot that night by the burn victim, including himself. Only a three-year-old child survives.

The March 16 tragedy was followed by a tremendous outpouring of shock, grief and mourning. Those who mourned were not only ones who knew and loved Steve Lovato and the other victims. Countless other people who did not personally know any of them deeply cared and wept.

March 16 became Roswell’s own nine-one-one. Those nationally known numbers had once only been known as those used to dial an emergency dispatcher to send help. Then the numbers began to also signify frightening incidents to which various emergency personnel responded. After a fateful day in September — 9-11 — they also began to refer to a specific national tragedy when, along with thousands of citizens, hundreds of emergency personnel died in the selfish act of saving the lives of others.

Locally, dialing 9-1-1 connects the caller with the Roswell Police dispatcher, who — depending upon the emergency described — dispatches law enforcement, fire and ambulance emergency personnel to the scene. In the early hours of March 16, people from all three departments responded.

No one expects a paramedic to be killed, especially not by a bullet, while dispensing medical aid to injured and fallen victims, and especially not by one he is aiding.

Within hours that same day, the AMR office began to fill with sympathy cards, floral bouquets and stuffed animals. Teams from the American Medical Response of Las Cruces and Alamogordo arrived to provide additional resources to the Roswell station during the crisis of losing one of their own.

Following the tragedy, the Roswell Fire Department, the American Medical Response, medical personnel of ENMMC who work closely with the paramedics, law enforcement officers and the City of Roswell gathered close, offering each other support and comfort. The community at large — far beyond Roswell’s city limits — did as well.

At Steven Lovato’s service, the church could not contain everyone, including those in various emergency service uniforms — paramedics, ambulance drivers, firefighters and law enforcement officers — who came to show their respects to him, his family and his coworkers. Hundreds of people attended his service, and almost as many ambulances and other emergency vehicles from near and far made slow procession along with private vehicles through the city streets in route to the cemetery while a medic helicopter flew overhead.

According to Cliff Halls, New Mexico Operations Manager, Lovato had been an accomplished Emergency Medical Technician in Roswell since 1998, when he received his initial EMT training in Las Cruces. In the press release, Halls also said Lovato had received numerous honors for his accomplishments and professionalism. He was a company safety officer, a driving instructor and received AMR’s highest award for service to others. Halls said Lovato also was recently selected as a company mentor to help teach and develop other EMTs.

Several people, including his father, Lawrence Lovato, quoted Steve as often saying how much he loved going to work and serving his community.

Lovato’s paramedic partner said at his funeral, “He was my hero, not because of the way he died, but because of the way he lived.”

The Roswell Web Magazine salutes Steve Lovato and the family he left behind, as well as all emergency personnel and law enforcement officers who selfishly serve their communities bringing safety, aid and comfort to those in need.

Greater love has no man but to willingly lay down his own life helping others. Our son, Steve, died on 3/16/02 doing just that. That is how he was raised, that is how he lived, and that is how he died. He would have done the same for all of you, dear ones.

We the parents (Lawrence & Rosie), the wife (Josephine), the son (Alex), and family of Steve Lovato thank, from our innermost beings, every member of our community. From the most prominent to the most ordinary person who honored our son.

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine