While water is a valuable resource and not an industry or commodity, it is the lifeblood of all industries and economic stability of entire communities and regions.

Communities and industries of the Pecos Valley are critically dependant upon water — in New Mexico, more precious than gold. Because of an ongoing drought situation throughout the Southwest, water, or the lack of it and how to deal with the serious problem, has been of utmost importance. The following piece written by Bernice D’Abadie is based upon her talk to the Roswell Women’s Club on April 9.

D’Abadie comes from a Roswell pioneer family and is an expert on this area’s water history.

The 100-year feud between Roswell and Carlsbad over water in the Pecos River has been temporarily settled! Now, who doesn’t believe in miracles?

Two kinds of water exist in this Pecos Valley — surface water and underground water. They are interconnected to some extent. In some places, ground water runs into the Pecos River.

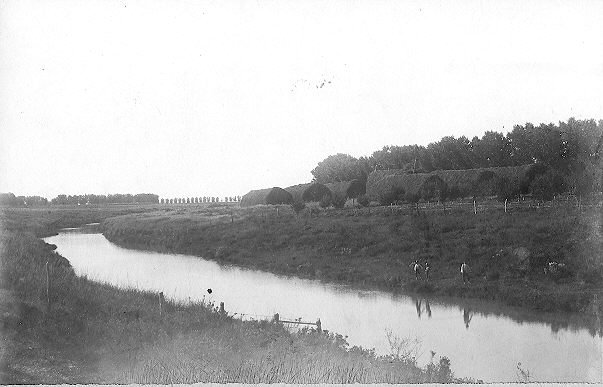

Our story begins in 1889. James J. Hagerman and Charles B. Eddy had a grand vision of developing the Pecos Valley with the abundant surface water from the Pecos River and its tributaries. They planned to irrigate thousands of acres and make the Pecos Valley a mecca of prosperous towns, farms and ranches. They acquired the Hagerman Canal (Northern Canal) east of Roswell that extended to Lake Arthur (about 25 miles south of Roswell); dug the Southern Canal as well as two lesser canals in Carlsbad; built a railroad into Carlsbad from Pecos, Texas, extending it to Roswell; and constructed the Avalon and McMillian dams on the Pecos River.

On August 5th, 1893, disaster struck. A huge flood came down the Pecos River and destroyed Avalon Dam. Hagerman and Eddy began to quarrel over management of the disastrous situation. It became more heated when Hagerman wrote to Eddy saying, “If you will quit lying about me, I’ll quit telling the truth about you.”

Neither changed his thinking, and Eddy was forced out of the irrigation company. I think that was the beginning of the quarrel about water between Roswell and Carlsbad.

Hagerman used his own money to rebuild Avalon Dam, clean up the canals and ditches, and repair miles of railroad tracks that were washed away. It cost $150,000.

Hagerman continued to expand his empire. He extended the railroad from Roswell to Amarillo, Texas. Another large project he tackled was the Hondo Reservoir Project. By damming the Hondo River nine miles southwest of Roswell, he and the town fathers planned to irrigate 100,000 acres of fertile prairie.

Hagerman never finished the Hondo Reservoir. He let it go to the U.S. Government for $20,000. The Hondo Reservoir was finished by the Reclamation Service in 1907 and it turned out to be a giant sieve. The water poured in and the poured out the bottom to who knew where. During its five years, the reservoir only irrigated 1,000 acres. That was our first reservoir — it was a graveyard to the dream of irrigating with surface water. Hagerman got out just in time.

In September 1904, another huge flood came down the Pecos River and destroyed Avalon Dam a second time. Hagerman had moved his interests to the Roswell area and there was no one who wanted to rebuild Avalon. The entire Carlsbad Project was sold to the U.S. Government for $150,000. It is now called the Carlsbad Irrigation District, or CID for short.

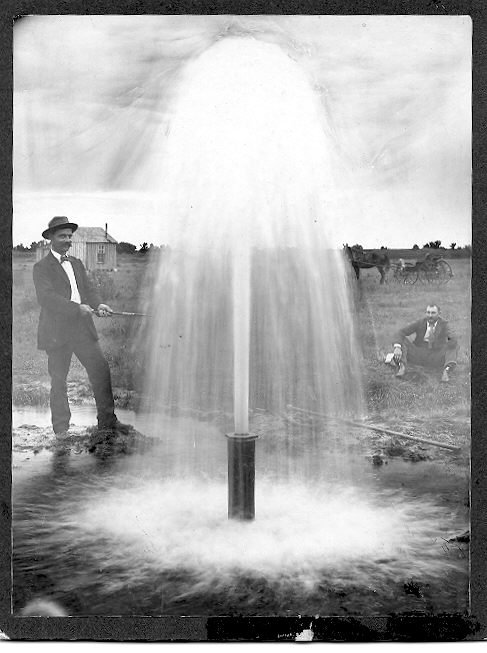

Roswell had an ace up its sleeve. The Roswell Artesian Basin had been discovered and wells poured forth excellent underground water. Over the years, we have irrigated over 130,000 acres of productive land with our groundwater. But there were troubles along the way. By the 1930s, the artesian pressure was gone and wells had to be pumped. There were no laws regulating underground water. Anyone who wanted to drill a well could do so and use all the water he wanted. If the well was in bad shape and leaked, no one did much about it. Some flowing wells were abandoned to run day and night for no useful purpose. Some wells were plugged by jamming a telephone pole down the casing and pouring some cement on top. All this leaked water into the shallow basin which fed the Pecos River. A survey in 1927 found the base flow of the Pecos River below Roswell was very good. Kay Havenor, a Roswell hydrologist, claims much of that water came from leaking wells.

When the flow diminished, the Carlsbad Irrigation District complained and accused Roswell of over-pumping the artesian basin and putting more acres of land into cultivation. They felt robbed.

Dr. Austin Crille — you may remember him –was the man responsible for reducing the excess flow. He talked and talked and acted to get groundwater laws passed. His son, Herman Crille, and Harold Hurd, Peter Hurd’s father, both lawyers, wrote the underground water act. The laws were adopted by the New Mexico Legislature and went into effect in 1931. The Pecos Valley Artesian Conservancy District was also set up at that time. It began plugging abandoned and leaky wells. This saved the Roswell Artesian Basin the first time.

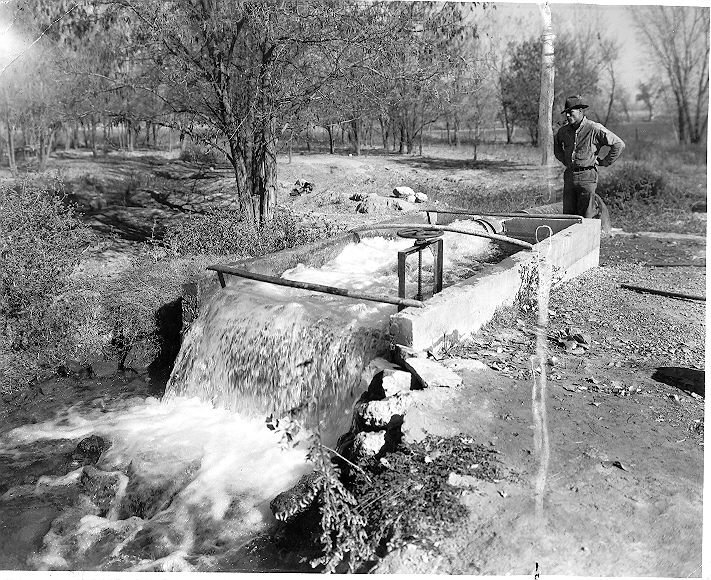

We had periods of drought in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. The level of water in the Roswell Artesian Basin dropped more than 120 feet and salt water began to pour into the basin. To save the basin, the never-ending State v. L.T. Lewis water adjudication case was brought into the Chaves County District Court to determine how much water a well owner could use each year. In 1966, a meter was attached to each well to measure the water used. Fred Henninghausen, the first water master in Roswell, used his quiet fairness with people to get the meters attached and he didn’t get shot at, even though some independent thinking farmers didn’t want water meters on their wells.

After 25 years, the artesian basin returned to a decent stable level. The Pecos Valley Artesian Conservancy District bought 7,000 acres or 21,000 acre-feet of water rights which it holds to keep the water level in the basin steady. Even with metering and retiring water rights, Carlsbad complained that not enough water came down the Pecos River, and Roswell was to blame. In 1976, Carlsbad Irrigation District gave notice that it would ask for a priority call. Roswell and Carlsbad have fought tooth and nail over than because wells in the Roswell area could be shut down if their priority dates were not older than 1928.

Trouble of much larger proportions fell upon all of us — Roswell, Carlsbad and the State of New Mexico. In 1988, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against us in a lawsuit brought by the State of Texas. Much earlier, we had agreed to share Pecos River water with Texas about 50-50 in an agreement called the Pecos River Compact. The amount of water owed was determined by river conditions as they existed in 1947. Texas claimed we had not delivered enough water and the Supreme Court ordered that we had to pay Texas $14 million for the shortfall that we hadn’t delivered to them since we signed the compact in 1949. The worst part was an order that if we fell short of delivering the amount of water due Texas in the future, we could not pay the debt with money; we had to pay the debt with water within a six-month period.

We had been in a crunch for the last two years, and have just barely stayed out of trouble. We are now looking at a long and severe drought.

The State of New Mexico said, “We cannot have the Sword of Damocles hanging over our heads year after year when it doesn’t rain. We must do something to get water to Texas t hat we can count on.”

New Mexico found some money to buy water rights, formed a committee to find a long-range solution and threatened not to pay anyone a cent until Carlsbad and Roswell stopped their feud. The situation was so desperate that Carlsbad and Roswell began to talk. The compromise they reached was the biggest surprise in our water history.

Basically, Carlsbad will cancel the priority call. In return, New Mexico will buy water rights in the Roswell Artesian Basin, and if Brantley Lake gets too low, well water will be pumped into the lake to give Carlsbad Irrigation District water for irrigation. Because water is needed to be sent down the Pecos River to Texas, New Mexico will also buy surface water rights in the Carlsbad Irrigation District and groundwater rights north of Roswell to Ft. Sumner, as well as more water rights in the Roswell Artesian Basin to meet a Texas shortfall. The maximum amount of water that can be taken out of the Roswell Artesian Basin was set at 20,000 acre-feet a year on average, a figure which won’t dry up the basin. The water experts think we can maintain the artesian basin as the Reservoir of Last Resort.

The compromise wasn’t perfect. It limits the agricultural economy of both Carlsbad and Roswell, but we may become friendly enough to successfully fight Texas and the federal government over the control of our water if we stick together. We might even be able to challenge the 1947 Condition which has worked such a hardship on our part of the state.

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine