VARIOUS VERSIONS OF PAT GARRETT’S DEMISE

Don Bullis of Rio Rancho, New Mexico is author of several fiction and non-fiction books, and a columnist for two newspapers. He also electronically publishes the New Mexico Historical Notebook. He wrote and published the following pieces and articles in several NM Historical Notebook issues–in March and April 2006. They are republished here with his permission. (Because they were separately published, Bullis begins each article with a brief introduction to the case, giving the official version of Garrett’s murder.)

These pieces pertain to the murder of Sheriff Patrick Floyd Garrett in 1908 near Las Cruces. Bullis provides, and annotates, the different versions of that shooting published in various sources. Sheriff Pat Garrett is best known for shooting Billy the Kid Bonney in Fort Sumner in 1881.

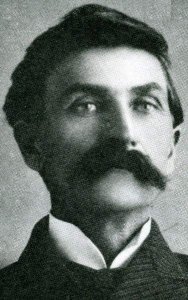

A petty criminal named Carl Adamson (1856-1919) was present when former Lincoln and Dona Ana County Sheriff Patrick Floyd Garrett was murdered on February 29, 1908 near Las Cruces. Adamson had previously served prison time for smuggling Chinese people into the United States from Mexico. There were, and perhaps are, people who believe that he was in fact Garrett’s killer. He was related to Jim Miller, who some also suspected of killing Garrett. Jesse Wayne Brazel confessed to the killing but was acquitted upon a plea of self-defense, but one writer asserts that Brazel and Adamson both shot the old lawman. Adamson was never charged, and as the only [known] eyewitness to the crime, was not even called upon to testify at Brazel’s murder trial. Adamson died at Roswell of a fever.

^^^^^^^

WHO SHOT SHERIFF PAT GARRETT??

Part I: A Hard Life

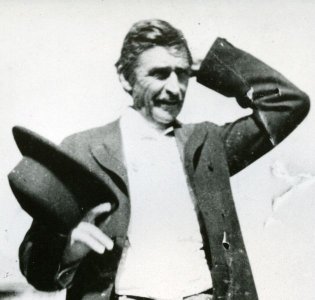

Former Sheriff Pat Garrett was shot to death on February 29, 1908. By then, more than a quarter century had passed since he shot and killed William H. Bonney (Billy the Kid) at Fort Sumner, New Mexico (July 14, 1881). The intervening years had not been particularly good to Garrett.

In the first place, Governor Lew Wallace, who had left New Mexico at the end of May, 1881, declined to authorize the payment of the $500 reward offered for the capture or killing of Billy the Kid. Garrett was obliged to attend the territorial legislative session in February 1882 and plead his case by lobbying on his own behalf. His style seems to have been buying drinks for territorial solons, and he succeeded in influencing them favorably. The reward was paid, but observers generally agreed that Garrett’s lobbying effort made the $500 a break-even proposition.

Garrett decided not to seek reelection to the office of Lincoln County Sheriff in 1882 after serving a single two-year term. Instead, he stood for Territorial Council, which was similar to the modern-day State Senate. He lost in a tough race.

He also produced a book called The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid.* Garrett didn’t actually write the book–his good friend Marshall Ashmun Upson did–but he hoped it would make him some money. It didn’t. And to make matters worse, the historical accuracy of the book’s content was seriously questioned. One critic said, “The whole book can be picked to pieces from beginning to end.”

By 1884, the former sheriff was operating a ranch along Eagle Creek, not far from Roswell. He may have had a margin of success at ranching, but it was a sedentary life compared to his earlier adventures, and he was soon drawn to West Texas where he organized the so-called LS Rangers. The ostensible purpose of the “Rangers”** was to put a stop to cattle rustling on the LS, and other cattle ranges. It soon became clear that big ranchers expected Garrett and his men to kill rustlers, rather than arrest them. Garrett declined to continue under those terms and the LS Rangers were disbanded in early 1885.

Back at the Eagle Creek ranch, Garrett demonstrated his acuity of intellect when he envisioned a vast irrigation system that could water the Pecos River valley and turn the area into a lush farming district. He participated in several companies organized to dig ditches and divert the waters of the Pecos. In the end, though, Garrett was forced out by his partners and his entire investment of cash and time was lost.***

In 1890, Garrett ran for sheriff of the newly created Chaves County, and was defeated by John W. Poe, the same man who had accompanied him when he killed The Kid, and the same man who succeeded him as sheriff of Lincoln County. An unhappy Pat Garrett packed up and moved to Uvalde, Texas in the spring of 1891.

Life in Uvalde didn’t suit Garrett. He seems to have done fairly well at horse breeding and racing, but he became restless and soon began looking for greener pastures. Dona Ana County, New Mexico, provided just such a location. On February 24, 1896, he returned to New Mexico specifically to investigate the disappearances of Col. Albert Jennings Fountain and his son, Henry. Both had vanished near the White Sands on February 1, 1896. In May 1896, Garrett was appointed Sheriff of Dona Ana County.

Still, Sheriff Garrett’s luck did not improve much. The main suspects in the Fountain case were Oliver Lee, Jim Gililland and Bill McNew, He arrested McNew without incident. Lee and Gililland were a different story. The sheriff and his posse trailed them to Wildy Well, a spot near the present-day Oro Grande, south of Alamogordo, and a major gun battle erupted when he attempted to arrest them. When the gun-smoke and dust cleared, one of the posse-men was wounded and dying and Garrett and the remaining lawmen were forced into an ignominious retreat. The outlaws remained free. Lee and Gililland were subsequently arrested–not by Garrett–tried and acquitted.

Garrett remained Dona Ana County Sheriff until 1900, during which time he or one of his deputies killed Billy Reed while effecting an arrest at the W. W. Cox Ranch. He was nearing 50 years of age and looking for some other line of work. The Federal Government beckoned.

In December 1901, President Teddy Roosevelt–over loud protests by some disgruntled Republicans–appointed the former sheriff as Collector of Customs for the Port of El Paso for a two-year term. He received a second appointment in 1903. There are many reports that during this time in his life, Garrett became something of a curmudgeon and spent a great deal of time drinking, gambling and philandering. His activities did not go unnoticed in El Paso, Las Cruces or Washington DC.

In 1905, Garrett and his friend, Tom Powers, an El Paso saloonkeeper and gambler, attended the Rough Riders reunion at San Antonio, Texas. Powers hoped for an introduction to President Roosevelt. Garrett obliged, introducing Powers to the President as a cattleman, and the three men were photographed together. Garrett feared that if he introduced Powers as a gambler, it would reflect badly on his own reputation. When the President learned the truth of the matter, he was not even slightly amused. In spite of Garrett’s best efforts at damage control, he learned on December 13, 1905 that he would not be reappointed as customs collector.

Over the years, Garrett had acquired two small but well-watered ranches in the Organ Mountains, 25 miles east of Las Cruces. They were about the only assets he had, and he didn’t own them free and clear. He tried prospecting and mining on his property, but that never accomplished more than meeting expenses. He continued his drinking, gambling and womanizing ways, and his disposition became even more cantankerous. He was at odds with neighboring rancher W.W. Cox over some cattle, and Cox was not happy about the Reed killing. Garrett’s debts mounted and his debtors began dunning him and pursuing their claims in court.

In 1907, Garrett’s son, Poe, leased one of the ranches to Wayne Brazel–a Cox cowboy–for grazing purposes. Payment was to be ten heifer calves and one mare colt per year. Little did Poe Garrett, or his father, know that Brazel intended to graze goats on his property.

Garrett was in the process of trying to undo the arrangement his son had made when, on February 29, 1908, he began a ride into Las Cruces from his ranch. He rode in a buckboard with a man named Carl Adamson. They were joined along the way by Wayne Brazel on horseback. At a point near Alameda Arroyo, four miles east of Las Cruces, as he stood urinating, someone shot Pat Garrett. One bullet entered the back of his head and exited through the right eyebrow and the second bullet, fired after he was down, entered the stomach and ranged upward to the shoulder. Carl Adamson said the old lawman moaned once, stretched out, and died.

* The complete title of the book was, The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, The Noted Desperado of the Southwest, Whose Deeds of Daring and Blood made his Name a Terror in New Mexico, Arizona and Northern Mexico, a Faithful and Interesting Narrative. Its author was identified thus: “Pat F. Garrett, Sheriff of Lincoln Co. NM, by Whom he was Finally Hunted Down and Captured by Killing Him.”

** The LS Rangers should not be confused with the Texas Rangers. Garrett had no affiliation with the Texas Rangers.

*** The entire company, The Pecos Valley Irrigation and Improvement Company, failed by the year of Garrett’s death: 1908.

NEXT WEEK: WHO DID IT?

^^^^^^^^

DID YOU KNOW …

In this space last week I mentioned that Carl Adamson was present when former Sheriff Pat Garrett was murdered near Las Cruces on February 29, 1908. Western Historian John Tanner dropped a line about him. While I had said that Adamson had a prior arrest record for smuggling Chinese people into the United States, John reports that he was arrested in June 1908, after the murder, for “conspiracy to smuggle Chinese into the United States.” He was convicted and sentenced to 18 months in prison. This is an interesting point in light of the fact that another historian of my acquaintance holds that the real reason Garrett was killed was to gain possession of the old lawman’s ranch for the purpose of using it as a staging area for Chinese people smuggled into the U.S. from Mexico. (Other suggested motives for Garrett’s murder offered over the years have included revenge, water rights, a land dispute, and just to shut him up.) For those of you who like to see historical figures in your mind’s eye, Adamson was described in prison documents as a 40-year-old American, 5-feet-8-inches in height and weighing 185 pounds. After his release from prison, Adamson went to work for a Chaves County sheep rancher named A.D. Garrett. There is no indication that A.D. Garrett was in any way related to Pat, but the name is ironic. Thanks to John for taking the time to write. He and his wife, Karen Holliday Tanner, are the authors of Doc Holiday: A Family Portrait, probably the most definitive biography of the gunman/dentist; and Last of the Old-Time Outlaws: The George West Musgrave Story, an equally engaging narrative about one of New Mexico’s last Old West shootists and train robbers.

WHO KILLED SHERIFF PAT GARRETT??

Part II: Death in the Desert

Sheriff Pat Garrett’s unhappy life came to an end on February 29, 1908. He was shot in the back and died at 58 years of age.

(Ed. Note: Bullis’s paragraph wherein he reiterates the official version of events of Garrett’s death is omitted here.)

Adamson’s story was that he stood with his back to Garrett and Brazel when the shots were fired. He turned almost immediately, he said, to see Brazel holding a smoking six-gun. He rushed to Garrett’s side only to discover that the former lawman was dead. He covered the body with a robe and left it where it fell. Adamson and Brazel rode on into Las Cruces where Brazel surrendered himself to Dona Ana county Deputy Sheriff Felipe Lucero. Brazel claimed self-defense from the beginning.

The gears of the New Mexico Territorial criminal justice system began turning. On March 3, Brazel formally entered a plea of not guilty to a charge of murder. Dr. W. C. Fields testified that Garrett had no glove on his left hand and was obviously urinating when he was shot in the back of the head (Garrett was right-handed). The second shot was fired after the victim was already on the ground. Fields described the killing as cold-blooded murder. Bond was set at $10,000. Rancher W. W. Cox posted it later the same day and Barzel was freed. Brazel was indicted for murder on April 13, but he was not tried for more than a year, on April 19, 1909.

As one historian has said, “The case was prosecuted with appalling indifference and incompetence.” Adamson was not called upon to testify and Brazel swore that Garrett threatened him with a shotgun and that he only fired in self-defense. He denied that Garrett had been shot in the back. The jury began considering the matter at about 5:30 p.m. and returned with a verdict of not guilty about 15 minutes later.

There were, and are, nearly as many theories about what happened that day in 1908 as there are observers. Many at the time simply could not believe that a mild-mannered young man like Brazel–he was 31 years old, same age Garrett was when he killed Billy the Kid–would kill anyone, so they looked elsewhere. The most popular theory was that a hired killer named Jim Miller actually fired the fatal shots.

A meeting was allegedly held at the St. Regis Hotel in El Paso in 1907. Oliver Lee, Bill McNew, Carl Adamson, Wayne Brazel, W. W. Cox, Jim Miller and several others attended it. This scenario holds that each man in attendance hated Pat Garrett for one reason or another, but W. W. Cox is said to have arranged and chaired the gathering and to have volunteered to pay for the killing. Cox not only despised Garrett for killing Billy Reed (aka Norman Newman)* on his ranch, but he also wanted access to the water on Garrett’s ranch. Oliver Lee, it is said, conceived of the idea of using Wayne Brazel to lease the Garrett property for grazing, then running in a herd of goats. He knew Garrett would react badly, and that would force a confrontation that might lead to a shooting which could be called self-defense. Jim Miller, who was Carl Adamson’s brother-in-law, was engaged to do the deed, for a fee of $1,500.

Miller, the story goes, hid behind a low hill in a prearranged spot, and when Adamson stopped the buckboard, Miller simply shot Garrett and promptly returned to Fort Worth. According to this legend, the plan worked perfectly, and famed New Mexico lawman Fred Fornoff** did find empty Winchester cartridges on a low hill near the scene of the killing. (Why a professional killer like Miller would leave the rifle cartridges behind is an historical enigma.)

There were other theories. The Garrett family believed that Carl Adamson actually pulled the trigger. some report that both Adamson and Brazel shot Garrett. Another tale was that W. W. Cox ambushed Garrett, and Brazel took the blame out of loyalty to the rancher.

It is axiomatic in criminal investigations that things are usually as they seem to be, and that is probably the case in the killing of Pat Garrett.

Historian Leon Metz says this:

“That Brazel’s plea of self-defense was not consistent with the facts does not mean that he was lying about killing Garrett; it simply meant that he was lying about how he did it. Garrett’s death was clearly a case of murder, perhaps not premeditated, but murder nonetheless. Brazel feared the old man-hunter and possibly had a reason to worry about his [own] safety if the goat problem could not be settled amicably. The two men had argued bitterly, and when Garrett turned his back, Brazel took the safe way out and shot him. There were no conspiracies, no large amounts of money changing hands, no top-guns taking up positions in the sand hills. It was simply a case of hate and fear erupting into murder along a lonely New Mexico back road.”

Pete Ross, an Albuquerque prosecutor and historian, disputes the motives [given] for Garrett’s murder.

* Billy Reed was the alias of Norman Newman who was wanted for murder in Oklahoma, and was hiding out on the W. W. Cox ranch. In October, 1899, Garrett and deputy sheriff José Espalin went there to effect an arrest, and Espalin shot and killed Reed when the suspect resisted. Historian Metz says that Cox was not particularly annoyed by this affair, and in fact loaned Garrett money a couple of years later.

** Fred Fornoff (1859-1935) served as Albuquerque chief of police, Bernalillo County deputy sheriff, deputy U.S. Marshal, captain of the Mounted Police, and as a Santa Fe Railroad investigator. According to some sources, he believed that Jim Miller did the killing, but admitted that he could not prove it. Historian Chuck Hornung disputes this. His version of events will appear in a future edition.

Addendum:

Wayne Brazel married and acquired a small ranch west of Lordsburg a few years after the Garrett killing. In 1913, his wife died and he sold out and disappeared. Some say he died in Bolivia, perhaps killed by members of the Butch Cassidy Gang.

Jim Miller killed 20 to 40 men–depending on the source–during his lifetime. A year after the Garrett affair, he shot and killed, from ambush, a man named Gus Bobbitt near Ada, Oklahoma and was arrested for the crime. On the day that Wayne Brazel was acquitted in Las Cruces, New Mexico, April 19, 1909, a lynch-mob took Jim Miller and his three cohorts out of jail and into the barn in Ada and hanged them one at a time. Legend held that Miller admitted killing Garrett just before he was strung-up. A member of the lynch-mob denied that Miller said anything of the sort.

Sources:

Garrett, Pat F. The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid. University of Oklahoma Press 1954

McLoughlin, Denis. Wild and Wooly: An Encyclopedia of the Old West Barnes & Noble, 1975

Metz, Leon C. Pat Garrett: The Story of a Western Lawman University of Oklahoma Press, 1973 (This is the most definitive source on the life and death of Pat Garrett)

O’Neal, Bill. Encyclopedia of Western Gunfighters University of Oklahoma Press 1979

Richards, Colin. Sheriff Pat Garrett’s Last Days. Sunstone Press, Santa Fe 1986

Smith, Robert Barr. “Killer in Deacon’s Clothing,” Wild West, August 1992

Thrapp, Dan L. Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography University of Nebraska Press 1988

Next Week: The Pete Ross Version of the Garrett Murder Conspiracy

^^^^^^^^^

PAT GARRETT’S MURDER: THE PETE ROSS VERSION

The late Pete Ross, a Bernalillo County, New Mexico Prosecuting Attorney wrote an article about the murder of famed Sheriff Pat Garrett. Published in the December 2001 issue of Wild West Magazine, the item offers another chapter, and another prospective, to the infamous crime.

[Ed. note: In the interest of expediency and space, the first two brief introductory paragraphs giving the already covered official version of Garrett’s murder, have been deleted.]Adamson said his back was turned when the shots were fired, but that he turned almost immediately and observed Brazel holding a smoking gun. Adamson and Brazel left the body where it fell and rode on into Las Cruces. Brazel immediately turned himself in to deputy sheriff Felipe Lucero. He admitted to the killing but claimed self-defense.

Ross was certainly right when he said that it is unlikely that anyone will ever know for sure who killed Garrett. Many in 1908 did not believe that Brazel pulled the trigger and historians–amateur and professional alike–have argued the point in the years since. Brazel was, however, the object of prosecution for the crime and no one else was ever arrested in the matter even though many were rumored to have been blameworthy. Killin’ Jim Miller (Carl Adamson’s brother-in-law), W. W. Cox, Oliver Lee, A. B. Fall and others.

Territorial Attorney General James Madison Hervey made a plausible case for a murder charge at the preliminary hearing on March 3. Brazel was ordered held on that charge and bond was set at $10,000. Rancher W. W. Cox posted it and the suspect was freed.

Garrett was interred in the Odd Fellows Cemetery in Las Cruces on March 5. His pallbearers included Territorial Governor George Curry.

It is at this point that Ross adds a new dimension to the case. It has been long noted that the prosecution of Wayne Brazel was done with “…appalling indifference and incompetence,” but Ross goes a step beyond that. He endeavors to show why that was so, and who was responsible for it.

Governor Curry hurried to Las Cruces as soon as he learned of Garrett’s death from District Attorney Mark Thompson. Curry’s relationship with Garrett is worthy of note, especially in light of later events. The two men had been acquainted since the mid-1880s, and had apparently been friends for many of those years. Garrett even co-signed a bank loan for Curry at one point, and ended up paying it off when Curry defaulted during the Spanish American War. But their paths diverged by the turn of the century in 1901. Garrett was closely aligned with Republican President Theodore Roosevelt and Curry was a rising Democrat, closely associated with Albert Bacon Fall, W.W. Cox, Oliver Lee, Mark Thompson and others. There was no political capital in a friendship with Garrett, and besides, Garrett was dunning the Governor for repayment of the old bank loan.

It must be noted that Curry, Fall and others converted to Republican after the Spanish American War and military service under Roosevelt, but Garrett had a falling-out with the president, so there was still no political advantage in friendship with Garrett.

Ross does not believe that Curry had anything to do with the planning that went into the murder of Garrett. He does, however, imagine that the governor did the bidding of some of his friends to make sure that Brazel would be acquitted and that not enough evidence would exist to arrest or prosecute anyone else for the crime.

Here is what Curry did.

He called off investigation of the murder by Mounted Police Captain Fred Fornoff who early-on found evidence that implicated Jim Miller, according to Ross. Curry claimed, “The Territory does not have funds available for such an investigation.” This would be important if, as many believed, Jim Miller actually did the killing (for $1,500) while Brazel was paid to take the rap because the conspirators did not think he would be convicted.

Attorney General Hervey also did not believe that Brazel was guilty. Curry says, “[He] … declined to appear for the Territory, which had my approval.” Ross thinks that Curry, as the highest ranking official in the territory, had a bit more to do with it. This would be important because with Hervey out of the picture, prosecution fell to District Attorney Mark Thompson, and this is where the plot thickens.

Mark Thompson was the law partner of Albert B. Fall who was a close business associate of rancher W. W. Cox who actually employed Brazel as a cowhand. Fall had also employed the services of Oliver Lee as gun-hand. Fall, Cox and Lee were members of the alleged cabal that plotted the murder in the first place. So, Thompson would prosecute Brazel, and Fall, at the behest of Cox, would defend him.

The trial took place on April 19th, 1909. Thompson produced none of the available evidence that would have shown that Garrett was murdered, not shot in self-defense. He did not even call Adamson, the only witness, to the stand. He did not refute Brazel’s assertion that he’d acted in self-defense. The jury returned a verdict of not guilty in only 15 minutes. There was, according to one historian, “a barbecue to celebrate Wayne Brazel’s acquittal” that very evening at the W. W. Cox ranch. “[As] the liquor flowed…the…occasion turned into a celebration over the death of Pat Garrett.” Cox had already acquired Garrett’s ranch.

And why did all of this happen? Ross says that the conspirators were on the way up in their political careers (Curry would become a congressman, Fall a U.S. Senator, Lee a state legislator), and Garrett was a nuisance. Curry owed him money, Cox held a lien on Garrett’s ranch and wanted the water rights thereupon, and Lee was still angry that Garrett had targeted him for the Fountain murders 10 years before, and had, in fact, tried to kill him. Garrett’s murder settled all those accounts and perhaps many others.

On the other hand, why would such prominent men run the risks involved in conspiring to do murder? Garrett, at 58, was past his prime and had virtually no political clout left. He’d managed to alienate most of his friends and spent much of his time drinking, gambling and philandering. He held no public office and had no prospects of same.

Whichever position one takes, Ross provided readers with a valuable insight as to how government, politics and business worked in Territorial New Mexico.

Sources:

Henning, H.B. ed. George Curry, 1861-1947, An Autobiography UNM Press 1958

Metz, Leon. Pat Garrett, the Story of a Western Lawman University of Oklahoma Press 1973

Owen, Gordon R. The Two Alberts, Fountain and Fall Yucca Tree Press 1996

Richards, Colin Sheriff Pat Garrett’s Last Days Sunstone Press, Santa Fe 1986.

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine