Editor’s note: My mother, when she was young, knew Sol and some of his family in Roy, as well as in Springer later, and she taught some of his great-grandchildren. I’ve known several of Sol’s descendents in Springer and Roy, and considered Irma Bibo Floersheim, widow of Sol’s son, Ben, my friend. However, I had not heard of Sol’s “Billy Tale” until recently when his great-grandson, Richard Floersheim, sent me the book Guts and Ruts as a gift. He has also since sent me excerpts of some of his grandfather Carl’s memoirs and, upon my request, copies of family photos.

Sol’s son, Carl, and other family members described him thus: “He was five feet tall and 110 pounds but packed full of dynamite, fearless, and his hobby was licking big men. He was unusually strong, very agile, a veritable tiger and when he hit, a man went down.”

Sol’s son, Carl, and other family members described him thus: “He was five feet tall and 110 pounds but packed full of dynamite, fearless, and his hobby was licking big men. He was unusually strong, very agile, a veritable tiger and when he hit, a man went down.”

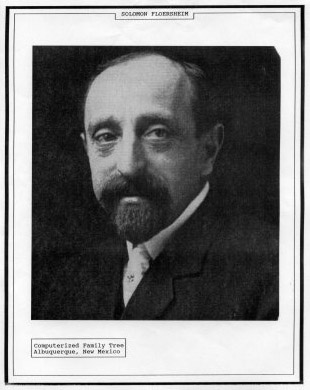

The story of the biggest little man in New Mexico was written as a memoir by his son, Carl Floersheim, Sr., in 1953. Using excerpts from those memoirs, portions of Solomon Floersheim’s story have been published in various places, including: Southwest Jewish History: The Fearless Sheepherder on the New Mexico Frontier; in a 1998 article by Sherry Robinson in the Wild West magazine: Another Version: How Garrett found the Kid; and also in Guts and Ruts, The Jewish Pioneer on the Trail in the American Southwest by Floyd S. Fierman, published by KTAV Publishing House, NY. And, by permission of the Floersheim family, told yet again here.

Solomon Floersheim was born in Hamburg, Germany in 1856, came to America at age 22, landing in New York near the end of 1878. There, he found a job working in a matzoh factory but soon found that he could not exist on $5-a-week pay. He began to drift towards the western frontier to seek his fortune … which he did later find, but he had some wild adventures before reaching that stage of his life.

After leaving New York, he was sidelined in Trinidad, Colorado in early 1879 because he ran out of money. That was the year the railroad track entered New Mexico from the north, but it played only an indirect role in Sol’s life and fortune. In Trinidad, Sol worked as a clerk for the pioneer family business, the Rosenwald Brothers, until he was hospitalized with typhoid fever. The Rosenwalds brought him fresh lemons and other specialty foods, but when his health improved and he returned to work, he learned they had charged him for all of those healthy treats, which he had mistakenly thought to be a generous gesture. That made him mad. He left town in the night, eventually landing in Las Vegas, New Mexico towards the end of that year.

His first job in Las Vegas was as a salesman, delivering liquor to mobile saloons that followed railroad workers. He began to carry a pistol after seeing a man shot to death.

Carl Floersheim wrote, “My father started to work for Mr. Charles Ilfeld, a real pioneer of those days, sometime in 1880. He worked for him about seven years as clerk and as collector in the outlying districts that were adjacent to Las Vegas, which was then a very important trading point. Collections from ranchers consisted mainly of receiving wool and sheep twice each year–wool in June, sheep in October. It was on one of those collecting trips that my father had occasion to encounter the Southwest’s famous outlaw, Billy the Kid. It seems that on July 12, 1881, my father’s destination was a sheep ranch about 15 miles southwest of Fort Sumner, New Mexico, which was the home area of Billy the Kid.” Because of the dangers of traveling alone and the likelihood of the rancher speaking only Spanish, Sol had brought another man with him.

According to his story as told to his family and later recorded by his son, Carl, that night a weary Sol and companion sought a resting place in or near Fort Sumner. The 23-year-old man and his helper stopped at a small building to make inquiries. Sol knocked on the door and was invited to enter. The men found themselves in a saloon with just one customer, another young man. Sol asked him for directions to the sheep ranch and where he could find a place to eat and sleep.

“My father was told of two places, and turned to go out when the young man asked him to take a drink of whiskey. My father told him he did not care for any. The young man drew a pistol and pointed it at my father and said, ‘You drink,’ and he did.

“The young man then inquired where he was from, his name, what he was doing and what his possessions were. While they were talking, he asked my father to take another drink. Of course, until then my father did not know that he was facing Billy the Kid [someone about whom he had already heard and read].

“Evidently he must have been in good humor when he met my father.”

“My father had on his person a very fine Colt Winchester .45 pistol and he started kidding the outlaw and even offered to trade guns with him. Billy preferred his own pistol that had killed at that time 21* men. My father even had the nerve to ask Billy to come and see him when he came to Las Vegas, but the true fact was that he never wanted to see him again.

“My father did not remain in Fort Sumner that night. He was afraid Billy might change his mind and kill him and his companion so he traveled all night and about 5 a.m. next morning, they arrived at a ranch house that, to my father’s pleased surprise, was occupied by the famous Sheriff Pat Garrett and family. Garrett was also a good friend of my father and mother. Pat had my father stay at his home a few hours for rest after my father had explained to him what brought him to his ranch at such an early hour. After a good breakfast and a few hours’ rest, Garrett said to my father, ‘Sol, let us go back to Fort Sumner and get Billy.’ My father told him, ‘I saw all I wanted of that fellow. If you want him, you go get him.'”

In this case, it would be no cliché to say, “and the rest is history.” Historians know that on the night of July 13, 1881, Pat Garrett shot and killed Billy the Kid Bonney in Fort Sumner in the bedroom of Pete Maxwell, son of Lucien B. Maxwell. (The senior Maxwell had previously possessed the nation’s largest individually owned piece of land, the Maxwell Land Grant in northern New Mexico.)

When Sol returned from his collection errand at the sheep ranch, heading home to Las Vegas, he again passed through Fort Sumner. There he was surprised to find area residents holding a wake over Billy the Kid and talking about his shooting by Sheriff Pat Garrett.

Some time after this, Sol was clerking at a store in Springer. The store owner had just paid him $27 when a bandit robbed him of all of it. Sol went after the robber, crossing the street to find him drinking in a bar.

“My father sneaked up behind him, swung the cowboy around and said, ‘Now it is my turn. Get your hands up and don’t you dare make a move or I will kill you.’ My father took the man’s gun and while his hands were up, rifled the man’s pockets, took all the money he could find and told him to leave town that very minute and not come back for at least four days. On returning to the store, he found that he had made a good profit as they [he and his boss] counted out $10 more than what was stolen from him.

“Some time later, my father told Mr. Ilfeld that he was quitting to go into business for himself. Mr. Ilfeld ridiculed him, told him he would not be able to make a living for himself. When my father left Mr. Ilfeld, he started a small store in a hamlet some miles north of Las Vegas and in that store he also had a small bar.

“It seems there was a blacksmith in this town who liked his whiskey and at times imbibed a little too freely. One day, the blacksmith came for a drink, then another and when he came for the third one, my father turned him down. That infuriated the 200-odd-pound six-foot blacksmith so he came back with a loaded rifle and pointed it at my father and said, ‘You give me all the whiskey I want, or I will kill you.’ My father asked him what kind he wanted and he said blackberry brandy. My father grabbed the bottle by the neck and smashed the bottle in the blacksmith’s face and then proceeded to use his fists until he had the man begging for mercy. He then took the blacksmith to his home, turned him over to the man’s wife.

“About 25 years later, the man and his family came back through Springer and he called on my father. The blacksmith told my father, ‘What happened in your bar was the grandest thing that happened to me. You stopped my desire for liquor. You made a Christian out of me, you saved me for my family and I am pretty well-fixed now, have $50,000 in the bank.’

“To give you an idea of my father’s stamina and fearlessness, at age 70, he gave a young Spanish fellow, about 30 years old, a sound thrashing even though out-weighed by fully fifty pounds. He came into my father’s store in Roy, New Mexico and said, ‘Here is a relief order, you dirty little Jew and I don’t want you to rob me.’ My father threw off his coat and lit into this fellow, gave him such a hard licking that they had to call the doctor afterward to sew him up.

“At the age of 75, he had an encounter with a district judge in the lower part of New Mexico. My father was talking to some prospective seller of wool in the lobby of a Roswell, New Mexico hotel when this so-called judge walked through the lobby and greeted my father. The judge came back afterward and told the man to whom my father was talking, ‘Why are you wasting your time with this little Jew?’ My father looked at the judge and said to him, ‘I believe they call you Judge down here. I have another name that fits you better.’ The judge said, ‘What do you mean?’ My father said, ‘You big overgrown SOB, you know what I mean. Let me tell you something. I am proud of my religion but I am damned sight prouder that I never killed anyone in cold blood [which apparently the judge was known to have done].

According to his family, Sol also developed an understanding of medicine and doctoring. His son, Carl, said his father helped deliver 300 babies, and performed “all kinds of minor surgery, amputations and helped doctors in Caesarian operations.”

He supported his faith, temple and charities in his communities, but also helped churches of other faiths in his and other communities. He and Catholic priests and nuns were friends. Jewish historian, Floyd S. Fierman, credited Solomon Floersheim with what he called Sol’s finest characteristic: He had, by providing decent wages and housing, fairly treated Hispanic sheepherders in his employ in ways unusual for that era.

Solomon Floersheim became a highly successful businessman. Among other enterprises, he founded mercantile stores that sold dry-goods as well as groceries in Springer, managed and later owned by his son, Carl, and later by his grandsons Carl Jr. and Myron; and in Roy, managed and later owned by his son, Mickey. He also founded the huge Jaritas Ranch in northeastern New Mexico where at one time he ran 100,000 head of sheep. The Jaritas was later managed and then owned by his son, Benjamin, a respected cattleman. After Ben’s death, it was owned by his son, Donald.

Sol Floersheim with his three sons: (left) Benjamin, (center) Milton “Mickey” and (right) Carl (Sr.) Floersheim. Sol also had a daughter, Viola, married to Sidney Rosenwald, who was later part-owner of some of Sol’s enterprises.

In addition to mercantiles and a renowned ranch, Solomon Floershiem founded a dynasty of respected businessmen. Sol died January 31, 1946 at age 90.

His son, Carl Sr., who originally recorded his father’s history in a journal, portions of which were later used in various publications including this one, was born March 8, 1886, in Las Vegas New Mexico and died July 7, 1976 in Atlanta, Georgia.

[*rwm Editor’s note: That number, 21 killings to match the years of Billy’s life, had been a prevailing myth for years. A more likely number of killings fairly credited to Billy would be four or five.]

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine