It was a beautiful evening in June 1983 when I arrived in Purchase, New York. An hour from the city, the forest enveloped the big estates. The quiet was never disturbed because the houses were deep among the trees.

The Knopf residence was not impressive – a three-story house with dormer windows, dark like Tudor houses are – but it was the Alfred Knopf arboretum (a botanical tree garden) that enchanted me. In June, the wisterias, jasmine, the pink and red azaleas – all climbers – surrounded the front porch and door. They were lush and fragrant, so much so that I remember feeling dizzy.

I was glad to see dear Mr. Knopf. Some people would call him a man of dour mood, but to us – the working staff – he was always kind. He appreciated his cook, Grace Portonova, of Italian descent; his chauffeur, Arturo from Peru; his butler, Hans, from Vienna; Annie, the black full-time maid; his two Italian gardeners; and little Michele from France. We all had heard so many times about his grandmother walking from the Ural mountains, some 800 miles east of Moscow, all the way to Hamburg, Germany with her two brothers. She boarded a ship to New York, then married a distant Jewish cousin who was a lawyer in Manhattan. Alfred Knopf was born in that borough, not in New York.

That summer, Mrs. Helen Knopf went to visit her family in Oregon. I was to try to keep him at peace during the duration of her vacation. She was his second wife. He had published a book about Native Americans of Oregon written by her in 1943. He married her in 1967. His first wife and partner in publishing died in 1966.

If I may quote Alfred Knopf, he would tell his friends, “My main thesis has always been loyalty, whether it is dealing with authors or with plumbers.” In a New York Times interview on the occasion of his 90th birthday, Mr. Knopf said, “We used the grandson of the plumber to do repairs in this house that his grandfather worked on when we built it more than half a century ago.”

Mrs. Helen Knopf and I knew that the upkeep of the house was Helen’s department entirely, but to the journalist he gave the impression that he participated in everything! How many times I heard Helen sigh, “Poor Alfred can’t even tie his shoes.”

“Don’t worry, Helen, I don’t have to; Hans will.”

He was one of the last men of his century to be fully taken care of. His son, Alfred A. Knopf, Jr. came every Sunday from Westport. He would scold his father for his lifestyle. Theirs was a sad relationship. Alfred Jr. had been sent to military school at the age of 10; neither parent had time for him.

Helen Knopf and the staff were all devoted to Mr. Knopf. Best of all, we loved him.

So, I arrived on a Saturday evening and ate dinner with him. He told me that Toni Morrison had come to eat lunch with him and kept him company all afternoon. What a woman was this big black lady – professor, author and fabulous mother to her daughters! I can still see her coming through the kitchen door, hugging Annie and giving her sweets for her children. She would run upstairs calling, “Alfred, it’s me, Toni.”

Mr. Knopf had a liking for blacks and the Italians. “You see, Michele, not long ago, we were discriminated against. I remember going down to Florida for a vacation. All the hotels had signs, “No blacks. No Jews.” Some of us with blue eyes and light complexions could rent a room. We stuffed the toilets with paper. The Anglo-Saxons would not let us join their clubs so we built fancier ones!”

By 12 o’clock, Mr. Knopf went upstairs in his elevator. Hans was waiting for him. I went up to the third floor, read an hour, and slept until eight in the morning. I woke in the champagne-colored bedroom, listening to the big trees rustling against the slate roof. The sun was up. It was going to be a fine morning, good enough to have breakfast on the terrace. Mr. Knopf was up at six; he was a bit slow now. After all, he was 90.

After a fast shower, I put on a white skirt and pink blouse and tied a pink French shaded ribbon in my hair. Downstairs I went. Mr. Knopf was drinking black brulot coffee (an ancient method of brewing French coffee). That coffee was too strong for his heart, but he would chuckle it off.

“Helen, I have survived four of my heart specialists, including the infamous Dr. Tarnover – killed by his aged mistress.” She had shot him in his bed on a stormy night.

That morning, we ate our three-minute eggs and toast with English ginger-orange marmalade. I drank tea. I was forgiven because Blanche Knopf (the first wife) drank tea too. Mr. Knopf dressed for breakfast in a salmon shirt dotted with white, blue trousers and a jaunty straw boater donned for the outdoors.

I had studied the Sunday schedule the previous evening. I read to him what he liked from the New Republic and part of the New York Times. He did not mind my accent. All of his life, he had been surrounded by foreigners. I brought down a sweater and his cane. He just smiled at me with those very intelligent blue eyes. We went for a walk to enjoy his beloved trees, many in full bloom.

At 11 a.m., Alexis Lichine made his grand entrance dressed impeccably, as always. That day he wore a gray striped suit with a medium pink shirt, pearl cufflinks, a red tie and a red Russian double-eagle on his coat lapel. He was a wine authority, had his own winery in Burgundy, France. I learned a lot from those two men. They had the same passions – books and photographs and wine. (By the way, the best picture of Eleanor Roosevelt was taken by Alfred in 1940.) I descended many times into the small but exquisite cellar below. Behind an oak door that was eight inches thick rested the evidence of Alfred’s passion. In racks and bins were quantities of Chateau Lafitte-Rothschild 1945 and 1959. For Alexis Lichine I decanted a bottle of Chateau Cheval Blanc 1925.

We greeted Alexis in a comfortably furnished glass-enclosed sun porch lined – as were all the other rooms in his house – with bookcases. They drank wine. I excused myself and went upstairs to change into a little black dress that I accented with a bright scarf and a pretty pin.

Mrs. Knopf called. Hans took the call. He looked like a distinguished and silvery diplomat dressed in his butler’s black. Mrs. Knopf wanted to talk to me first, so I took the call in the hall on the second floor.

“I had a good flight. My three girls are happy to have me.” Her only son would not talk to her since she married Alfred, a Jew.) “I am going to have three weeks of rest; thanks you dear girl.”

“No problem. Mr. Knopf is happy with his friends.”

“Now. Michele, don’t forget that Wednesday Alexander and Irina Solzhenitsyn are coming for lunch. Order the Napoleon cake from the pastry shop in White Plains. You will make the borscht yourself.”

“Yes, Mrs. Knopf. Not to worry. And I will not forget to give fancy flowers to Irina and the two sets of iridescent marbles for their sons.”

“Now I will talk to dear Alfred.”

Hans went down to hand the telephone to Mr. Knopf. Alexis and I went into the main hall and talked about his winery in Burgundy. “It looks like it will be a good year if we don’t get too much rain in early September.”

During World War II, his family had been forced to escape to England. The Nazis had confiscated his estate, and all his beautiful bottles of his best wine went to Germany. Burgundy, after Paris, is the richest county in France. Alexis insisted I tell Mr. Knopf my grandmother’s story about the wolves that ran free in Burgundy, so I did.

Wild animals learn to eat the food that is available, so we had to guard the grapes. According to the peasants, during the times of famine over the centuries, the rocky wine-growing regions of France, where soil was unsuited for other sorts of agriculture, were frequent prey to and a prime attraction for hungry wolves that survived by eating the grapes. The people noticed something strange. The grapes had an “exhilarating effect” on the wolves. The peasants suspected the stomachs of the wolves were so constructed that the fermentation of the fruit juice proceeded rapidly after the animals had eaten the grapes. During the year of 1942, a drunken pack was seen running in a village in Burgundy. They came through the center of that little town; the wolves were all intoxicated. That was what caused them to come into the village in the first place, and it was also what saved the townsfolk. The wolves were too drunk to remember that they were wolves. They howled and drooled before collapsing in a stupor. The villagers, hunting knives in hand, stepped cautiously out of their doors. When the wolves did not move, they killed them all. That was the last wolf scare in Burgundy. According to rumors, the wolves had come all the way from Poland.

“Why not,” commented Mr. Knopf, “My grandmother walked all the way from Russia.”

Alexis added, “For me and my family, the last wolves left in 1944. Germany compensated us for our losses.”

By then, the three of us were famished. Arturo brought the Burgundy-colored Mercedes by the front door. We were to lunch at the Cremaillere in the country. Halfway there, Mr. Knopf, who always sat in the front, ordered Arturo to stop. “Stop right now. Michele, look at that big tree. In June 1940, Blanche collapsed under it. France had been invaded. Blanche had a fierce and abiding love for France and all things French.” We thanked him for sharing that memory. Mr. Knopf seemed wrapped in some private shroud of his own – weaving gloomy and taciturn. Yes, he could be a man of dour mood.

The restaurant was in a coniferous forest. It was a rural place with a roaring fire in an open hearth where the restaurateur grilled spitted chickens laced with marjoram leaves, as well as veal steaks. A Beaujolais of the previous autumn, very light and clear, lifted Mr. Knopf’s spirit.

“I give it a four!” roared Alexis – the best on his scale.

While eating, we observed the gorgeous, colorful birds outside – cedar waxwing, painted bunting, red crossbill – the wanderers of the pine forest. During desert, Alexis compared the birds’ songs to the great operatic performers.

Back in Purchase, we said our au revior to Alexis. Mr. Knopf answered some of his mail until half-past-five. I went up to my suite and called my family in France and in New Mexico. I called the fancy grocery store that delivered all the best food we needed for the week. They came in through the kitchen door, put it away in the refridgerator, freezer and neatly lined pantry. They left the bill on the kitchen table. I would give it to Eleanor Carlucci, his private secretary who resided in the city.

By six, Mr. Knopf was dressed in a gray suit with a blue shirt that matched his eyes. Away we went to Heineman’s down the way. He was famous in publicity on Madison Avenue. He had written a slogan for a French perfume. “Promise her anything but give her Arpege.”

Their house was huge with the grandest kitchen ever. Mrs. Heineman rented it most of the week to a television outfit that filmed soap operas in it.

“It helps us pay taxes on the place,” said her man to Alfred.

The dinner was a little on the heavy side, so Mr. Knopf asked me, “Do you mind watching Beverly Sills in an opera at home with me?”

“Not at all, Mr. Knopf.”

So we stayed up until 1 a.m. We drank slowly a full bottle of Taitinger Champagne, just to help us sleep. For me it was an evening of pleasures and reminiscences. He told me how much he liked Joseph Conrad. “He was an elegant, dynamic man. His books made us plenty of money.” Miss Willa Cather was probably his favorite author. “She was to me the girl from Nebraska.”

Blanche took care of the fancy foreign writers. He still had an eye for the ladies. He looked forward to the visit of Miss Liv Ullman, an actress from Norway. She liked to sleep in purple sheets.

I reminded myself that I had to get up at 6 a.m. to bake a fresh chausson aux pommes – baked apples in a slipper – for breakfast. Mr. Knopf kissed my hand and wished me a good night, “ma petite.”

He died a year later in August 1984. He was born in 1892.

I was to spend 10 summers in Oregon with Helen Knopf. She was a brilliant, courageous, loving person.

Michele was born in Alsace Lorraine, France on the German border, and was a small child when Germany invaded their province in June 1940. Her little sister was born then and her mother had to hide in the basement to give birth alone. Michele said, “You know we [France] have had three wars with Germany.”

She lived there until she was 20 years old, then moved to the USA, living here from 1957 to 1960. She was married in France in 1956 to Kenneth Wunderlick, a man from Kansas of European heritage, and from 1960 to1972, she again lived in Europe – in France, Greece and Germany – while her husband was in the military. With a dual citizenship, French and American, she has lived in the USA since 1972. Between 1980 and 1984, she lived both in New York and New Mexico, but by 1984, their home became Roswell.

For many years Michele lived off and on with the Knopfs; she went to stay with them for extended periods of time, including entire summers, whenever they called for her to join them.

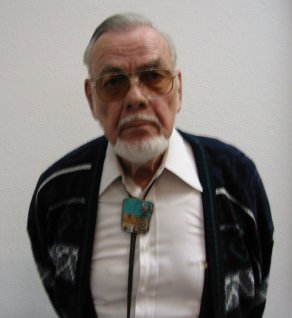

She lives in Roswell with her husband, Kenneth, and is a member of the Joy Writers group.

French is Michele’s native tongue, but in addition to English, she also speaks Greek and German. She said she practices her Greek every week when she talks by phone to relatives in Greece.

By Victor J. Reeves

I guess just about everyone has heard that old expression, “Sitting on a powder-keg,” and most already know it means “Caught in an extremely dangerous position.”

For this application, I will explain. (First, I had to learn that a keg can be used for other things besides beer or nails.) Many generations ago, when that expression was coined, farmers, loggers, road-builders, miners and many other developers had legitimate use for explosives. The simplest form, and the easiest to use with (relative) safety was black powder. It was not uncommon for anyone to have one or more kegs of powder sitting around. It was treated almost casually – too casually. Quite a few workmen, and even some children, had missing feet, arms or eyes to prove it. Needless to say, on a keg of powder was not a good place to sit.

Construction jobs used lots of powder, although it was usually the far more powerful, and better-controlled form, dynamite. It was stored and guarded by experienced “powder monkeys,” men who took pride in their profession and were widely respected. But once in a while, a worker who was not schooled in handling such touchy stuff would be assigned to handle it anyway, for expediency’s sake. Today’s story contains a little bit of that.

In 1946, I was working on a pipeline job, which I have mentioned in other writings. I was breaking in to the regular crew; I had been only a night watchman, and was in transition and still wearing a cast and limited to light duty.

If you have ever been the “new kid on the job,” or in the class or any group or clique, you know that you will probably be exposed to a lot of hazing or “raw-hiding.” This was no exception. I was several times daily told some cock-and-bull story that, depending on how I reacted, could get me into serious trouble, or at least make me the butt of their “hoorawing.”

One afternoon, about an hour before quitting time, Red, one of the old-timers – which meant anyone who had been there a day longer than me – hollered at me. “Hey, Reeves, you about done there? The big boss has a job for you and me.”

I said, “Yeah, I’m almost done (with one of their useless jobs; how would I ever know when I was done?). Be right there.”

Red said, “Jim wants me to take that ol’ powder-house down to the east end of the ditch, where they’ll need it first thing in the morning. He said for you to help me.”

I was glad to have a ride to the east end because I had to catch the truck there to go back to Carlsbad. I knew this was probably an elaborate scheme to get me into an embarrassing position, but I just had to play it cool – and wait my chance.

The house was about the size of a small one-car garage, welded together out of steel plate so that it was totally weatherproof. It was mounted on skids made of four-inch pipe.

Red backed the winch-truck up to one end of it, and I ran the cable from his winch over the six-inch roller on the back of the truck, under the end cross-member and back to the rear of the powder-house, and hitched it there. Red began to take up slack and the front-end of the house soon started to lift up. When it came up to the roller, all it could do was roll right on until it was approaching the “headache” bar. Red stopped the winch, and told me to attach two chains to the front of the house, pulling backward as the house crept forward. I stopped Red once, adjusted the lengths of chain and anchored them to the winch-truck. I signaled him to inch it up, and the two chains tightened just as the cable did. That house was standing at a 45-degree angle, with its skids only inches from the ground, and just as solid on the truck as if it had been welded to it.

Red said, “How did you know how to do that?”

I shrugged and said, “Oh, just lucky, I guess.” Actually, I had probably more experience with winch-trucks than he had.

Well, the wind was blown out of his sails, but it didn’t take him long to recover.

Starting to roll and to cuss at the same time, he took off down the non-road that had been scraped out of the hillside only a few days before. He drove like the devil was after him, which is the standard speed on all pipeline jobs. Cussing and mumbling about the rough ride, the constant wham-banging of the rear end of the powder-house hitting and dragging on the “road,” and the dam-fool who had hauled that house up to the west end anyway. Red never shut up.

He said, “This is the last time I mess with this thing. The only reason Jim put us on it was because we’re the two newest men he’s got. We’re expendable! I hope you said your prayers. You’re a family man, too, ain’t you?”

I nodded but I wondered, What does that have to do with anything?

“Well, I wouldn’t hesitate,” said Red. “If Jim tries to put me on this keg of powder again, I ain’t taking it. He can fire me if he wants to; there’s other jobs. An’ if I was you, I wouldn’t do it no more, neither.”

Boy, I thought, they’re really spreading it thick. It’s a good thing I know they’re just pulling my leg. Nobody in his right mind would be hauling dangerous cargo over any such chuck-hole and bolder patch as this. It’s only a big production for me. They wouldn’t have had to do it up quite this brown, though.

The scariest thing about that fool’s ride was the way the front end kept coming off the ground and you had no control. But like he said before we started, “We’re both pretty good-sized and can lean forward and it will usually go down for a few seconds.

Finally, the east end of the ditch came in sight and Red began to slow down. He was watching for a signal so he would know where to park our cargo. When a guy waved him into a spot, Red swung around and pulled on through the area where they were indicating (because he couldn’t back up) and stopped. He slacked up on the winch, told me to unhook that and the two chains, and stand back. “WAY BACK!”

Would you believe this? He simply drove out from under that monster, which fell with a resounding clang like Big Ben sounding off. Or maybe World War II.

I only had about 10 minutes to get over to the truck for my ride to Carlsbad, but Red said he wanted to see if everything was okay in the house. He had to get a key from the straw-boss. All of this was making me more and more impatient.

When the door swung open, a great WHOOSH of dust billowed out, so thick we couldn’t see into the house. But it soon cleared away and we could inspect our load.

There, row upon row, top to bottom in that house, were stacks and stacks of DYNAMITE; at least 100 cases of it.

I thought I was going to throw up.

But I didn’t.

I had passed. I was in. But they still got my goat.

Oh, yes; your guess is as good as mine. Were the cases empty? I never found out. I really didn’t want to know!

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine