The horse racing industry and its many peripheral industries are off and running in New Mexico. The racehorse-related industries were given potent tonics with the introduction, passing and governor’s signing of pertinent bills in the New Mexico Legislature.

Four bills were passed in the 2001 New Mexico Legislature and signed by Gov. Gary Johnson. One allowed the New Mexico Horseman’s Association and the New Mexico Breeder’s Association to use 20% of the interest earned on the balances of any fund for purses that came from gaming to offset additional administrative costs caused by adoption of the gaming tax statute. Another bill loosened some of the rules of who could be licensed to work at New Mexico racetracks. A third bill allowed gaming machines to accept large currency bills, and a fourth allowed racetracks to increase the number of their in-house gaming machines. Racetracks cannot long survive without the additional revenues from supporting casinos and gaming machines.

In previous years, several State Legislative bills were also passed and signed by the governor to allow owners and breeders of horses bred in New Mexico to share generous purses for stakes and overnight races.

The New Mexico Horse Breeders Association distributes incentive award monies for the racing seasons ending at the conclusion of the New Mexico State Fair, per laws and regulation enacted by the State Legislature and the New Mexico State Racing Commission. A percentage of the straight pari-mutuel handle and a percentage of the exotic pari-mutuel race handle at all New Mexico race tracks is transmitted each week to the Association for distribution as incentive awards to winning New Mexico bred horse owners, breeders and stallion owners.

In 1992, the Legislature passed provisions for 50% of the breakage on pari-mutuels at New Mexico racetracks to be allocated to enhance race purses of certain races that included only horses registered as being bred in New Mexico. The Association receives breakage from race tracks and distributes the funds to enhance New Mexico bred stakes race purses at the tracks where the breakage was earned.

In April 1993, Legislation decreed that about 1/3 of the unclaimed pari-mutuel tickets from each race be used to enhance each track’s overnight purses for races restricted to horses bred in New Mexico.

Each of the state’s racetracks must pay a10% breeders award, that is 10% of the winning purse provided by the racetrack track, to the breeder of any winning horse bred in New Mexico. The New Mexico Breeders Association confirms the New Mexico bred status of each winning horse.

Breeders of New Mexico bred horses that win stakes races are awarded money by the racetrack; the New Mexico Breeders Association confirms those breeding records.

In February 1999, the New Mexico Gaming Commission adopted rules enacted by the State Legislature to allow 20% of the net take from gaming at the racetracks to go to race purses. The New Mexico Horsemen’s Association distributes more than 80% of that to the existing purse structure, and the balance is distributed to the New Mexico Horse Breeders Association Gaming Purse Fund. That fund is divided equally among the Incentive Award Fund, the New Mexico Stakes Fund and the Overnight Purse Fund. Two of those funds — Stakes and Overnight Purse — are distributed back to the racetrack from where they came.

Currently, there are five racetracks in New Mexico: Ruidoso Downs in Lincoln County, the Downs at Albuquerque, the State Fair Race Track in Albuquerque, Sunland Park in southeast New Mexico and SunRay Park and Casino at Farmington in the Four-Corners area. The SunRay racetrack, licensed and opened summer of 1999, was formerly the San Juan racetrack. In the past, there had been two other racetracks, now closed: Santa Fe Downs, and La Mesa Park at Raton in northeastern New Mexico.

Proposals have been recently submitted for new racetracks at Hobbs. One of those proposals is for Lea Downs Racetrack and Casino, with races proposed to begin in the fall of 2002. Another proposal is for Zia Park, by Zia Partners Bruce Rimbo and R.D. Hubbard who are associated with Ruidoso Downs. The Zia Park proposal plans for racing to begin at their projected $26 million Hobbs racetrack in the fall of 2003. Hearings before the New Mexico Racing Commission on proposed tracks have begun.

Because usually only 10 horses run in each race, and there are a limited number or races per day during racing season, there are more racehorses than opportunities to race them. Racehorse owners believe an additional New Mexico racetrack would enhance those opportunities.

Racing season varies at each of the racetracks. Some dates overlap, but there is horseracing at one or more of the New Mexico racetracks throughout the majority of the year. Quarter horses and thoroughbreds are the breeds running on New Mexico’s racetracks.

Breeding, mare care and foaling of the current generation of race horses occurred long before those horses were on the track. And while they race across New Mexico, the U.S. and far beyond, the next generation of potential race horses is being bred, born and nurtured.

The story of horse racing begins with the racehorse, which begins with the breeder, long before the birth of the horse. One might think that story began at the horse’s conception. However, before that, the physical characteristics, genealogies and racetrack histories of its potential forebears were scrutinized. The records of parents, and their ancestors, of the horse-to-be were carefully considered before it was conceived. Winning racehorses rarely happen by accident anymore. Horses are selectively bred to be winners.

The next step, that follows the breeder’s careful selection of the stallion, is also not left to chance. The breeder is directly involved in the physical coupling of the life-creating cells of the parents. In the case of quarter horses, the breeder artificially inseminates the mare, or dam, with the sperm of the chosen stallion, or sire. Because blooded racehorses are such valued assets, artificial insemination assures neither parent is injured in the excitable natural process of mating. Artificial insemination also assures vitally important documentation of the offspring’s bloodline, and control of its due date.

So … the story of the racehorse begins with its breeding, which is an industry of growing importance in New Mexico because of the added monetary value of horses bred in New Mexico, thanks to the enactment of pertinent state legislation.

The beginning of the horse’s story does not end with its selective breeding. After insemination, the breeder regularly examines and monitors the mare to assure her pregnancy has begun and is proceeding normally.

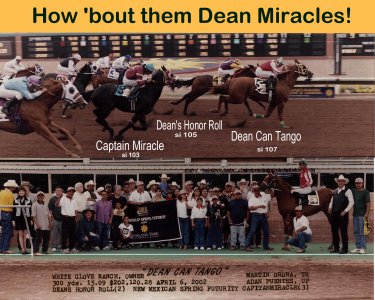

Located at Roswell is a renowned New Mexico horse breeder, equine veterinarian Leonard Blach, located at Buena Suerte Equine east of town. Horse owners primarily from New Mexico and West Texas, but also from much further locales, use his services. On his premises are several champion studs. Those include Dean Miracle, Danzatore, Devil Diamond and Straight Talker, who have sired many race track winners within and far beyond New Mexico, including in Europe. World Champion Dean Miracle was the sire of the first, second and third place winners of a recent race at Sunland Park, probably a first in racetrack history. Currently, Dean Miracle is the leading freshman sire in the nation. Track winnings from the offspring of one champion stallion can be in the millions. Because of artificial insemination, it is possible for each champion to sire hundreds of horses per year during his stud career.

Following breeding, another industry steps into the story of the horse: Mare Care.

HunterCreek Farms, east of Roswell, has year-around mare care and complete foaling facilities. This premier mare care facility is associated with Dr. Blach and the Buena Suerta Equine facility. Professional medical care is readily available to HunterCreek Farms, since Buena Suerte Equine and Dr. Blach are conveniently nearby.

As race horse breeder, Blach is the matchmaker and baby-maker. HunterCreek Farms is the maternity ward, delivery room and nursery. Susan Hunter is the midwife. She closely monitors and documents the progress of each mare and attends the birth of every colt.

HunterCreek Farms, on its 42 manicured acres, has nine very large turnout paddocks and 16 large indoor stalls. Like Buena Suerte, this facility is located near Roswell, in southeastern New Mexico, just 70 miles from Ruidoso, on the Tatum Highway, which is one of the main arteries between Texas and Ruidoso Downs. The fenced facility has an electronic gate for added security.

The two facilities, Buena Suerte Equine and HunterCreek Farms, work together. Buena Suerte developed the proper daily grain ration fed to the mares, and Susan and Kerry Hunter assure good quality hay is always available to them “free choice.” Whenever Susan, Kerry or their staff are not physically with the mares and their babies, the animals are under close surveillance. The barn stalls and paddocks are equipped with video surveillance cameras, monitored from the barn office or the main house. Owners of the boarded mares receive monthly reports on procedures, including veterinary care, and a website provides them easy access to their mares’ progress and photos. The website also gives absentee owners the opportunity to present their animals, along with their pedigrees, to potential buyers.

HunterCreek Farms’ mare care facility houses an average of 60 to 80 mares year around. Many of the owners are from West Texas. The first 2002 baby was born there January 22. By the time this issue is published on the Internet in mid-May, all 76 babies will probably have been born. Mares are bred so that their babies are born as close to January as possible, because their age is given, for the racing record, as being one year old the January following their births. If a baby is born late in the year, actually making him just a few months old the next January, that places him at a disadvantage when he is matched to others labeled as one-year-olds who actually are close to that age.

Mares do what comes naturally, they don’t need help having babies, some people say. The same can be said of people: women have had babies without assistance since human life began. However, human mortality rates were once extremely high, especially for babies and mothers, compared to those with proper medical supervision. In third world countries, where mothers don’t have that luxury, mortality rates remain high, and the number of serious side-effects add to the perils of birth. Obstetric fistula is just one of many of those side-effects. After days of painful labor, hundreds of thousands of women in third world countries are left with serious internal tears that breed infection and interfere with bodily functions.

Horses, like people, benefit considerably by having assistance available if something goes wrong. As the monetary value of selectively bred mares and their foals increase, owners cannot afford to leave them alone to do what comes naturally.

The average mortality rate for horse births is 10%. Susan and Kerry Hunter are happy that they have lost only two babies out of the large number of colts born at HunterCreek this year, which is a much better success ratio than average. Their babies are healthy and have had no serious injuries.

While riding with Susan and Kerry as they made their rounds to feed mares late one day, we were amazed to see how relaxed and socialized their boarders are, and how well acquainted the Hunters are with each mare and mare’s baby entrusted to their care.

“See that one over there?” said Susan, pointing to one of many beautiful mares standing in a large paddock. “That’s Granny Was a Good Old Girl. This is her miracle baby,” she said, ushering a spry, long-legged sorrel colt towards us.

She and Kerry then told us about the harrowing birth of Char Mamaw’s Miracle. The story, parts of it sounding like a fairy tale, really began when Susan’s beloved grandmother died and Susan hoped one of the many pregnant mares would have a baby on March 6 to commemorate her Mamaw’s birthday. Granny — whose owner had named her for her own grandmother — was expected to soon foal. Late on March 6, Granny began labor but had a serious complication, an obstetric fistula. The colt’s sharp hooves badly tore Granny’s rectal and vaginal walls. Part of the colt was shoved down one canal and part of it was pushed down the other. The majority of the colt’s body was hung up by what remained of the membranes that normally separated the two passages.

Untended, this critically urgent situation could have led to the long painful death of the mother, and the baby’s life would have never begun. With no time to summon Dr. Blach, Susan and Kerry did what they had to do to free and deliver the colt, which was stillborn. The mare’s birthing contractions had applied pressure on the colt, caught across the throat by the tissue dividing the two passage walls, and it was choked.

Normally, a newborn colt takes his first breath when he is half-way out of the mother.

Susan applied mouth-to-mouth resuscitation — actually it was Susan’s mouth blowing into one of the baby’s nostrils while she tightly closed its mouth and other nostril — as Kerry applied chest compressions. The colt began to breath on her own. The mare will undergo extensive surgery for repairs, but the filly seemed unaffected by her traumatic beginning. When we saw the two several weeks later, they looked like any other healthy mare and colt in the paddock.

When the owner of the colt, who already had a name chosen for her, heard the story of her birth and what Susan was calling her, she decided Mamaw’s Miracle was an appropriate name; Char Mamaw’s Miracle became her official name.

Dean Miracle is the sire of Mamaw’s Miracle.

After 11 months and 10 days of pregnancy, mares outwardly show little evidence that labor is about to begin. Waxing — a waxy discharge from the mare’s teats — and a subtle difference in the teats’ appearance, are the only clues Susan has to tell when to move that mare into the delivery stall for even closer monitoring. When labor begins, the mare becomes restless. Labor generally lasts one to six hours, the water breaks and a normal birth takes about 20 minutes.

Most births happen in the night, when the environment quiets down, under the cover of darkness. In the wild, horses are prey, and if they think conditions are not good, mares are able to delay birth for up to two days. Compared to many mammal babies that are totally helpless at birth, colts are fairly self-sufficient. Soon after birth, they are able to get on their feet, and even run if they must. When there is no stress, colts begin nursing within an hour or so of their births.

While we were at HunterCreek, Susan moved an expectant mother from a paddock into one of the barn stalls. That mare, Roan and Groan, was restless, almost panicked, because she could not see her friend. Susan returned Roan to the paddock, where her friend was within her sight, for a while until she quieted down. Horses are social animals and develop close attachments with each another. When giving birth and a few days afterwards, however, mares and their babies are safest when they are isolated from the inquisitiveness of other mares.

Susan Hunter has developed another business related to her mare care facility and the horse racing industry. Barns and sheds for horses and other types of livestock are usually made of metal, which won’t allow transmission of signals. Because of her need for a working monitor system for her entire mare care facility, Susan designed cameras and transmitters that work in buildings of various construction.

Susan’s systems fit her own needs so well that she began marketing them to others all over the U.S. She specializes, with her warrantied HunterCreek Video Systems, in various types of wireless (or wired if the customer prefers) barn cameras to monitor foaling, sick or injured horses. Some of the systems are designed for outdoor pens and runs; others are designed for horse trailers to monitor animals in transit. Susan also markets an infrared LED system that allows viewing in total darkness. The systems can be used in dairy barns and for other types of livestock, but are not limited to animals. They are applicable to other types of businesses and situations requiring video and audio monitoring, including home security. Except for the television or VCR, the systems are complete, with — depending upon the system ordered — wide-angle cameras, 350 degree scanners, antennas, receivers that can operate up to four cameras at once, remote control devices and wiring if required. Susan said electronic advancements have made these systems affordable.

Susan has been around horses her entire life. She grew up on a ranch in Big Spring, Texas, and a room in the HunterCreek barn is filled with the many ribbons and trophies she won in Howard County, Texas and many other places for her expert horsemanship. Besides her other talents, she is musical; she sings and plays the keyboard. She belonged to an entertainment musical ensemble that toured the country for many years. That was a great experience, she said, but it did not satisfy her love of working with horses. Before going into the mare care business, Susan and Kerry raised and bred show horses. They still own show horses, including a huge, approximately 1,400 pound, leopard Appaloosa stallion named Packn Heat. Years of traveling with the band and its fancy sound equipment gave her electronics experience. Her knowledge developed from that, she said, leading to the video systems she designs and builds that have become a sideline business.

Besides the video systems, Susan has designed breakaway weanling and suckling halters. Colts get accustomed to wearing halters, while the breakaway design keeps them from getting caught in possibly dangerous situations.

Kerry has a sideline business related to the racing industry, also. But not horse racing. Due to his life-long love of Porsches, he manufactures various types of Porsche racing headers. In addition to his two different types of “horsepower” businesses, Kerry is employed with Harvard Petroleum, a Roswell based independent oil and gas producer, which is another important industry that fuels New Mexico.

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine