An agreement was made in 1829 between the two republics – the United States and Mexico – that each would provide, along their own portions of the Santa Fe Trail route, troops for protection to the travelers on the Trail. It was that which first brought U.S. General Stephen Watts Kearney to New Mexico, and which caused the United States to begin to covet that land known as New Mexico. U.S. Topographical Engineer, James William Abert, Trader Josiah Gregg and several soldiers with the Army of the West kept journals as they traversed the Trail during those eventful times.

When they marched over Bonney’s land at La Junta, James Bonney marched – briefly and unmemorably to all but a few who cared – into recorded history.

Those various early-day journalists, historians and descendents of James Bonney said he was born in England or that he was a blue-eyed Irishman from the British Isles. He was described as handsome, with red hair and beard. That he had blue eyes has never been disputed. Those blue eyes, which must have been a dominant gene, have passed down for generations.

James immigrated to the United States, some stories say a brother came with him, and he settled in Missouri – where and about when the Santa Fe Trail began.

For a while, it was said, he ran a successful freighting business over the Trail from Missouri to Santa Fe and back again. About 1825, he began a settlement at what was then called La Junta – the junction – because of the fertile valley made by the crossing of two rivers, the Mora and the Sapello.

He settled in northern New Mexico and began another family. Bonney carefully chose the site for his trading post. It was Mora grant land, located at the lower plaza, given to him by his new father-in-law, Miguel Mascarenas. The place he wanted, and which Miguel deeded to him, was beside the Santa Fe Trail. In fact, it was near where two of the Trail’s branches – the Mountain Branch and the Jornada or Cimarron Cutoff with the Ocate Crossing – joined and became one before it went on to Santa Fe. It was also beside the trail that went west, up over the mountain to the high valley of lo de Moro where a settlement of grantees – one of the earliest white settlements in New Mexico – was already established on the upper plaza.

The summer of 1846, U.S. Brigadier General Stephen Watts Kearney and his Army of the West passed through New Mexico and, without firing a shot, successfully claimed it for the United States from Mexico. When the battalions led by Kearney – one under the command of Alexander W. Doniphan, Colonel First Regiment Missouri Volunteers – marched over the Santa Fe Trail that had begun 25 years earlier, they passed through the “civilized valley” of La Junta. The soldiers considered it civilized because it had plentiful water, fine grass, flocks of sheep, droves of horses, and large herds of cattle. James Bonney had a settlement there, and the dugout dwelling, log cabin, trading post, livestock, garden and animal pens those early journalists wrote of were his.

Just a few years earlier, Bonney had hired Mexican laborers to dig an irrigation ditch from the junction of the two rivers to the higher ground where he built his settlement and trading post. That ditch, still functioning in the new millennium, is called the Bonney Ditch.

“The first settlement we had seen in 775 miles,” wrote Lieutenant Emery, a journalist with the Army of the West. He also wrote, “Mr. Boney (sic) … has been some time in this country, and is the owner of a large number of horses and cattle which he manages to keep in defiance of wolves, Indians and Mexicans. He is a perfect specimen of a generous, openhearted adventurer, and in appearance what, I have pictured to myself, Daniel Boone of Kentucky must have been in his day. He drove a herd of cattle into camp and picked out the largest and fattest, which he presented to the Army.”

Another early-day journalist who met him recorded that Bonney had red hair and beard and was an Englishman.

The battalions led by Kearney were guests of James Bonney on the night of August 13, 1846. His wet and bedraggled guests on the second night were those of the artillery battalion commanded by Doniphan, slowed by their wagons and cannons and the inclement weather. This history is found in several early records and journals.

Lore that passed down verbally for generations from Bibiana Martin’s family and from New Mexico descendents of Bonney have also said that those two groups of American soldiers spent those two nights camped beside the river on Bonney land and for their evening meals, James had fed them his choicest beef.

1846 was a memorable year for the very young Bibiana. Her son, Ramon, by James was born and soon after his birth came armies of American soldiers, the first she had ever seen, who were brief guests of her family. Less than two months later, James Bonney was killed in early October, not far from his home.

Indians had stolen some of his horses; the next morning, while the signs were still fresh for tracking, James took an Indian servant for translation, and a bag of freshly made tortillas for barter, and went in pursuit of his horses.

His arrow-studded body was later found beside Dog Creek, beyond Valmora. It is said that he was buried in what later became the Tiptonville cemetery. There are still some who believe they can identify his unmarked grave.

No American forts had yet been built along the Santa Fe Trail, because the Territory had only just become property of the United States, but soon there would be many. In 1851, the first Fort Union was built near what had been James Bonney’s trading post. That fort was, perhaps, built upon Bonney land. At any rate, Bonney’s grown children told Fort Union they owed them rent.

In New Mexico are many descendents of James Bonney. Most of them come from Cleofas, Santiago (James Bonney, Jr.) and Rafaela – his three children by Juana Maria Mascarenas. Juana was the daughter of Miguel Mascarenas, the 42nd grantee of the Mora Land Grant and that liaison was recognized as a marriage in early New Mexico court documents.

Some New Mexico descendents also came from Ramon, the son of James and Maria Bibiana Martin, the daughter of Apolonia and Bernardo Martin, the 40th grantee of the Mora Land Grant. The one between James and the very young Bibiana was his second child-producing relationship in New Mexico, but his third known family.

James had an earlier relationship or marriage in Missouri that produced children. Historian, Herman Weisner, connected a blue-eyed Englishman named James Bonney to a family in Missouri. Into that family, said my friend and published historian, was born a child named Catherine who might have later become the mother of Billy the Kid Bonney. Weisner found several coincidences or links to believe that was a possibility. Herman died in January 2003 without fully proving his theory.

In the middle of the year 2001, I traveled back more than 150 years in one hour of one day. What transported me was being told that I stood upon the site where James Bonney had built his dugout dwelling, store and trading post along the Santa Fe Trail in the early 1800s. Who transported me was 74-year-old Joe Lopez who has startlingly blue eyes. He said he got them from his great-great-grandfather, James Bonney. Joe owns some of that land that Bonney had owned so long ago. That included the site where we stood that day.

Years after James Bonney’s death, his Mascarenas descendents legally fought for and regained ownership to his lands from Samuel B. Watrous, Tipton and other settlers of the area who had taken possession of them after Bonney died.

The settlement, known as La Junta 150 years ago in northeastern New Mexico, was renamed Watrous. Also in the area of Watrous had been two other settlements. The better known one, still often found on maps, was called Tiptonville after an early area settler.

After James Bonney’s adult children by Juana regained his lands – Rafaela’s husband, Trinidad Lopez, founded the other settlement. Soldiers at Ft. Union recommended to Trinidad – who had himself once been a lieutenant, Company A, First Infantry stationed at Ft. Union – to establish a community to protect himself and his family from Indian attacks. The adage of “safety in numbers” was then even more poignant. Trinidad named the settlement Bonneyville.

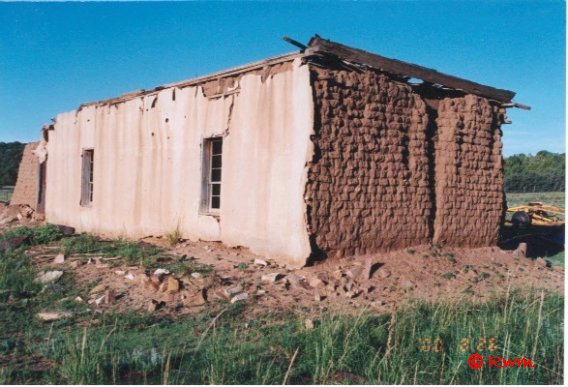

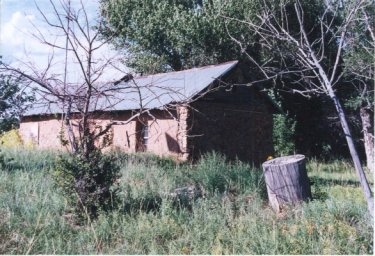

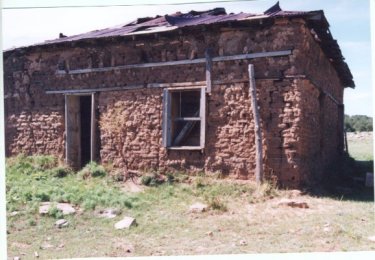

Cleofas, Santiago and Rafaela and their families built their adobe homes there, as did many others. The three adobe Bonney abodes still stand, but only one or two non-Bonney abodes remain. Still, if you look closely and know what you are looking at, you can see foundations and indentations, stones and adobe, the earthly remains of Bonneyville, as well as a Jesuit church and cloister founded by Cleofas.

Although I am not descended from James Bonney, he has always fascinated me because Bibiana Martin was my great-great-grandmother. She later had other children in addition to Ramon, one of whom was my great-grandmother.

there was a boy called Billy in the Territory of New Mexico.

Now Billy wasn’t his name back at the beginning of his life;

they say that it was Henry and he was born to one then not a wife.

His mama’s name was Catherine, and he had a brother named Joe.

His mama’s last name was McCarty, so too was his and Joe’s.

Most historians say Henry McCarty was born without a dad

in New York to an Irish lassie and the way they lived was sad.

Our Henry had arrived there on his birthing day

in an Irish slum in 1859, so some historians say.

Still, little is known about him, back in his early years

except knowing how to feed him was his mama’s greatest fear.

They lived a while in Kansas, made a stopover in Denver too;

why they landed in New Mexico, historians have no clue.

What was it drove them onward? Why did they end up here?

Were they searching for a better life, or was it plain despair?

Some say their lives got better before arriving here

’cause Catherine took a partner to share her load with her.

At any rate, they came here, to live in this wild place,

Catherine, Joe, Henry — and Will, a guy historians trace

to Kansas on the plains, a place called Wichita.

Even then, young Henry called William Pa.

So, long before they got here, they’d ambled other places,

frustrating historians by leaving few traces.

Census, courts and archives, even churches cast

few if any clues upon our mysterious Billy’s past.

One thing they know for certain (at least they think they do) —

the Santa Fe Book of Marriages holds their first recorded clue.

The widow, Catherine McCarty, in Santa Fe, New Mexico,

stood with Henry and Josie (what they called her boy Joe) —

as she said her wedding vows, the boys stood up with them

at First Presbyterian with her and William Henry Antrim.

That was the first known record establishing when he —

our Bonney lad — was in New Mexico: that was in 1873.

Like his mom, Henry McCarty right then changed his name

to Antrim. “William or Will like my new pa, if it’s all the same.”

Confusing historians, he was Henry McCarty just the same,

but William Henry Antrim right then became his name.

In Santa Fe the Antrims’ days of wandering still weren’t done;

they traveled to Silver City to bask in its arid sun.

It was there the young William Antrim, called Will,

took yet another name. “Just call me The Kid or Bill.”

Then his beloved mother died of consumption or T.B.

It broke the heart of Billy; a boy he’d no longer be,

for there the young lad, Billy, began his criminality.

On a lark he stole some clothes from a Chinaman’s laundry.

It was only for the fun of it, but the sheriff did not laugh.

The Kid was thrown in jail but his lock-up did not last.

The Kid determined a little space with just a cot and pail

was not to be the end of this, our cunning Billy’s tale.

He conned the sheriff’s deputy, and knew well how to shimmy

so he made quick his escape right up that red brick chimney.

That proved to him and all the rest his wiles and slippery ways,

and that was just the beginning of his desperado days.

(Now what could you expect, since Billy’s home life wasn’t sound?

And his step-dad didn’t care much to have the boy around?)

He was a homely kid, buck-teeth and prominent ears,

so he relied upon his ways of charm and lack of boyish fears

to win him loyal friendships, cause girls to think him cute.

Still, his winning way was because … boy, could he shoot!

So … who was our Henry McCarty, William H. Bonney, “The Kid?”

Where did he come from, who was his ma, why did he do what he did?

Of his latter years (alas, so few), we know his story well

for many, including Pat Garrett, his stories loved to tell.

His antics, shoot-outs, hot pursuits are documented well

in books, in movies and in songs, stretched out so they would sell.

And sell they did, even in England, for folks there love a tale —

of strife, romance and intrigue as they quaff their brew and ale.

***

The origins and genealogy of Billy “The Kid” Bonney and his early life remain a mystery. So too is the mystery of why he, in the latter portion of his short life, adopted the name Bonney. Most published historians think that: a.) He began life in New York as Henry McCarty; b.) He changed his name to William Henry Antrim to match his stepfather’s after his mother’s marriage in Santa Fe in 1873; and c.) He adopted the name William H. or Billy Bonney in the last years of his life. Historians don’t know from where he acquired or why he adopted the Bonney name. Serious historians admit that they are uncertain of his origins, but think he might have been born in a New York City Irish slum in 1859. Both the place and the date of his birth could be incorrect.

“All of our visitors are special, but we think some are really out of this world!”

Rwm

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine