(Nisha Hoffman, author of the following article, is Public Relations officer of Fort Stanton, Inc. — a non-profit 501(c)3 corporation dedicated to the historical preservation and restoration of this only fully surviving fort in New Mexico. The corporation hopes the site will become a multicultural historical park accessible to everyone. This corporation depends upon donations and volunteers. If you are interested in doing either, or in knowing more about this historically valuable site, visit http://www.fortstanton.com/ RWM)

Listen to the echoes. The jingling of the harnesses, the chink of spurs, the rattling of sabers, the bugle. At Fort Stanton, the past is only a breath away. Standing in this valley under Sierra Blanca for 147 years, Fort Stanton has seen nearly continuous service.

Built in 1855 as one of a string of buffer forts to protect settlers from the Apache, Fort Stanton was named for a young dragoon captain. Captain Henry Stanton was posted to Fort Fillmore. A newlywed, he had waited anxiously for his bride to reach New Mexico. She arrived in time for the holidays. A month later Captain Stanton was killed in a skirmish with the Apache.

Detailed out of Fort Fillmore, Captain Stanton was to aid Captain Richard Ewell out of Fort Thorn in returning some 2,500 sheep that had been stolen by the Apache. The Apache had been harassing the men most of the day and while the main body of troops remained to set up camp, Capt. Stanton led twelve men into a deep ravine. The Apache were waiting. In the fire fight which followed, one of Stanton’s men was hit. Capt. Stanton stayed with Thomas Dwyer, the fallen soldier, to cover the retreat of his men and was himself killed along with John Hennings. The soldiers later returned, wrapped the bodies in blankets and buried them. In an effort to hide the graves, they built fires over them. It didn’t work. Four days later, when they came to retrieve the bodies, the graves had been exposed, the blankets taken and the animals had been at the bodies. Under the circumstances, the bodies were cremated and only the bones returned. One Private Bennett recorded in his diary:

“We rode into the fort. Mrs. Stanton, the Captain’s wife, stood in the door awaiting her husband. If a person had one drop of pity, her he could use it on. Poor woman! She asks for her husband. The answer is evaded. An hour passes. Her smiles have fled. Her merry laugh is turned to sighs, and tears stain her cheeks. Him, she loved, she never more shall behold.”

In April, 1855 Major James H. Carleton and Colonel Dixon Miles converged on a valley on the Rio Bonita and picked a site for a fort, giving it the temporary name of Stanton after the young Captain. In the end, the War Department agreed and kept the name.

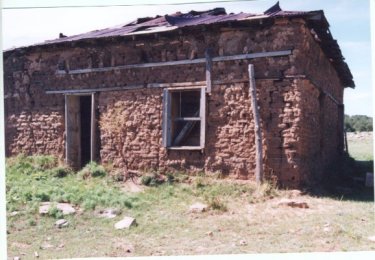

Dragoon Bennett appeared on the scene at Fort Stanton in August, 1855 and reported that construction was well under way. He reported on the completion of quarters for eight officers, one company of enlisted men, a guardhouse and commissary and quartermaster storerooms. Intended to be another adobe fort, someone decided to make use of the abundance of river rock, and a stone fort was built.

Lydia Lane, wife of Lt. William Lane, came to the fort in 1858 with her daughter Minnie. Lydia was to go on to a number of forts in New Mexico but always remembered Fort Stanton fondly as having the coziest of quarters of any fort where she was stationed.

With the coming of the Civil War, officers had been quietly drifting away from New Mexican forts to go back to Texas and rumors were running high. When word came that Fort Fillmore had been abandoned and the Confederates had taken Mesilla, Brevet Lt. Colonel Benjamin S. Roberts decided to abandon Fort Stanton. Rather than leave his artillery and stores to the Texans, he set fire to the fort. It didn’t work. One of those sudden rain squalls that sweep across the area put out the fire. Roofs were damaged but the Confederates walked into a well supplied fort.

Captain James Walker and his 2nd Regiment of Texas Mounted Rifles did not stay long at Fort Stanton. Not a large group to begin with, they were ill equipped to deal with the Mescalero who discovered in a short while that this was a different army. When sending out small groups of three and four, Walker was lucky if one returned. He left for the Mesilla Valley after only two months.

During this period, Fort Stanton was at the mercy of the locals and they stripped the fort of anything they could use in their homes, ranches, farms. By the time General Carleton sent Colonel Kit Carson to reactivate the fort, it had gone from the most comfortable of quarters to the most dilapidated. Carson’s orders were to make short work of the raiding Apache and he did not waste time rebuilding the fort. Putting a roof on the quartermaster’s stores was the main repair and the troops were left to winter in their Sibley tents. Carson’s campaign against the Mescalero was short and swift, resulting in their being placed on a reservation at the Bosque Redondo.

The next ten years brought some major changes to the fort other than its reconstruction. During those years, commanders at the fort would include Captain William Brady, Major Emil Fritz and Major Lawrence G. Murphy. George Peppin would be employed at the fort as a stonemason during this time also. These men would all reappear later on the same side in the Lincoln County War.

The famed Buffalo Soldier units would come to Fort Stanton. These soldiers would be instrumental in the fights against Victorio, Geroninmo and in the Tularosa Ditch Wars.

The years of 1877 and ’78 found Fort Stanton involved in a different kind of fight. The first of those was the El Paso Salt Wars. For years, Mexicans had been coming across the border to gather salt from the lake beds 150 miles east of El Paso. That was hotly contested by an American citizen who claimed ownership of the lakes. The end result was three Americans dead and Col. Hatch and the Ninth Cavalry being called in to stop the fighting.

The second fight was a good deal more severe and involved the Fort Stanton commander, Col. Nathan A. Dudley ignoring an order and becoming a posse comitatus for the Dolan faction in the Lincoln County War. Hostilities between the Murphy-Dolan men and the Regulators of Tunstall and McSween had escalated with the murder of John Tunstall in February 1878. Not long after, came the murder of Sheriff William Brady, a former commander at Fort Stanton. He was gunned down on the streets of Lincoln. Brady was replaced as Sheriff by George Peppin, the stonecutter employed at Fort Stanton.

Meanwhile, the citizens had been pressuring Col. Dudley to have the army take some action in this matter. He chose July 18, 1878 to show up on the streets of Lincoln with troops and a mountain howitzer; that arrival was instrumental in the outcome of the day’s proceedings. While he always maintained he was there for the protection of women and children, he did threaten the Montano store and the McSween home. Both contained women and children. He also used his troops to surround the McSween home and to escort the sheriff on his rounds. At a court of inquiry, he would later deny taking any sides in the dispute. The army, at its best in protecting one of its own, found insufficient evidence for the charges. The only outcome of any value was that Col. Dudley was transferred.

Following the Lincoln County War, the Indian situation became the prominent trial for the men of Fort Stanton. The Mescalero had been on the reservation now for some time and had developed large herds of cattle that fell prey to the consistent rustling practices in Lincoln County. The army was expect to track down those cattle, return them and punish the rustlers. Couple that with the illicit sale of liquor to the Indians, and the army had more than enough work to do. Then in 1880, Victorio started raiding again. A number of Mescaleros left the reservation to follow Victorio, and the army called out troops from as far away as Texas to aid the Fort Stanton Buffalo Soldiers in their pursuit. The Mescalero troubles drifted to closure with the death of Victorio at the hands of the Mexicans.

In August of 1887, Second Lieutenant John J. Pershing, not long out of West Point, was posted to the garrison at Fort Stanton. Pershing wasted no time getting started. Just one month after coming to the fort, he was involved in a campaign against a raiding party. His men pursued the Indians over 110 miles in more than 26 hours before capturing them.

This was the beginning of the end for Fort Stanton as a military fort. It would play a role in the economic and social life of Lincoln County for the next nine years, but would have little cause to be a military presence. The order to deactivate the fort came in October of 1895. On August 17, 1896, Lieutenant Black sent a report to the Adjutant General of the Army: “Sir I have the honor to report that the detachments at this post were withdrawn today and therefore no further returns will be rendered.”

In April, 1899 Fort Stanton was turned over to the United States Marine Hospitals. It would become a tuberculosis sanitarium for the Merchant Marine. But that is another story!

(Information for the above article is from: Fort Stanton and Its Community by John Ryan; Fort Stanton, New Mexico the Military Years by Lee Myers; I Married a Soldier by Lydia Spencer Lane; and The Lincoln County War by Frederick Nolan)

We hope Nisha Hoffman will continue to contribute to the Roswell Web Magazine historical articles about Fort Stanton’s various stages of life. A hoped-for follow-up is one covering the days of the Merchant Marine TB sanitarium. RWM

====================================

Fort Stanton has led a long, interesting, and diversified life. From its establishment during the Indian Wars and involvement in the Civil War and Lincoln County War, it served as a military stronghold. Although decommissioned near the end of the 19th century, it continued to function as a federal hospital, then as a state hospital.

* Fort Stanton was established May 1855 to control Apaches in the area.

* Fort Stanton was occupied by Confederate forces in August 1861.

* Fort Stanton was reoccupied by “Kit” Carson and five companies of New Mexico volunteers in October 1862.

* Fort Stanton brought stability to the area and encouraged settlement of Lincoln County.

* Fort Stanton was the dominant and ready market for local goods and services.

* Fort Stanton was a major control factor during the Lincoln County War.

* Fort Stanton was home to Buffalo Soldiers who helped control Apache bands led by Victorio and Geronimo in the 1880s.

* Fort Stanton is associated with several legendary figures, including: Billy the Kid, who was incarcerated in the guardhouse; Territorial Governor Lew Wallace, who is reputed to have written parts of his famous novel, BEN HUR while relaxing in the quiet of the isolated post; John J. Pershing, Commander of the American Expeditionary

* Forces in WWI, who served two tours of duty at the fort in 1887 and 1889.

* Fort Stanton was officially abandoned by the Army in 1896.

* Fort Stanton was turned into a Merchant Marine tuberculosis hospital by the Public Health Department in 1899.

* Fort Stanton was an internment camp for the crew of a German Luxury Liner that was scuttled off the coast of Cuba in 1939.

* Fort Stanton was transferred to the state of new Mexico in 1953.

* Fort Stanton entered the State Register of Historical Places in 1969.

* Fort Stanton entered the National Register of Historical Places in 1973.

* Fort Stanton entered the States Most Endangered Buildings list in 1999.

Fort Stanton is about to change again. This time, the cultural and historical heritage will be restored … forever!

The (envisioned) new Fort Stanton (will be) a multicultural historical park that offers a living history environment for the entire family, an equestrian camp for children, a camp-cottage hostel for the young and the young-at-heart, or a peaceful retreat for any organization. … (An) interpretive center offers educational exhibits for all ages featuring the Apache; the Spanish Conquest; the influence of the horse in the west; the military fort; the settlers and ranchers. Living history sites, such as the Apache encampment, Fort Bakery, the Smithy can all be visited on foot.

(At the envisioned “new” Fort Stanton, you can) take a hike or enjoy a wagon ride to see petroglyphs, ruins, caves and cemeteries. Explore on horseback the 26,000 acres of rolling mountain foothills filled with a beauty and serenity unmatched anywhere else in New Mexico, or maybe the world. Travel to and from Lincoln to see the history of the Lincoln County War. Get there on the only scheduled state line in the U.S.A. Enjoy a chuck wagon dinner and a camp sing-along at the end of a perfect day.

Fort Stanton is staffed by volunteers of Fort Stanton, Inc. in partnership with the Bureau of Land Management, Roswell Field Office; the Lincoln County Historical Society; the Mescalero Apache Nation; and the Ruidoso Valley Chamber of Commerce. WE CAN NOT DO THIS ALONE! WE NEED YOUR HELP. If you would like to support efforts to restore Fort Stanton, please send your contribution to Fort Stanton, Inc., P.O.Box 1, Fort Stanton, NM 88323 or visit our website: http://www.fortstanton.com/ You are invited to visit the Fort from Thursday through Monday 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

(Note: A large portion of Fort Stanton is presently off-limits to the public because it currently houses New Mexico drug-rehab residents. The Post Office and Museum are the only buildings now open to the public except for special occasions such as the recent Fort Stanton Live on Sunday, May 19th, which was part of the celebration of New Mexico Heritage Preservation Week. RWM)

“Born 1903-Died 1942. Looked up the elevator shaft to see if the car was on its way down. It was.”

In a Thurmont, Maryland cemetery: “Here lies an Athiest all dressed up and nowhere to go.”

On the grave of Ezekial Aikle in East Dalhousie Cemetery, Nova Scotia: “Here lies Ezekial Aikle, age 102. The Good Die Young.”

In a London, England cemetery: “Here lies Ann Mann who lived an old maid but died an old Mann. Dec. 8, 1767.”

In Ribbesford, England cemetery: “Ann Wallace: The children of Israel wanted bread, and the Lord sent them manna. Old clerk Wallace wanted a wife and the Devil sent him Anna.”

In a Ruidoso, New Mexico cemetery: “Here lies Johnny Yeast. Pardon me for not rising.”

In a Uniontown, Pennsylvania cemetery: “Here lies the body of Johnathan Blake, Stepped on the gas instead of the brake.”

In a Silver City, Nevada cemetery: “Here lies The Kid. We planted him raw. He was quick on the trigger but slow on the draw.”

A lawyer’s epitaph in England: “Sir John Strange. Here lies an honest lawyer and that is Strange.”

John Penny’s epitaph in the Wimborne, England cemetery: “Reader, if cash thou art in want of any, dig 6 feet down and thou wilt find a Penny.”

In a cemetery in Hartscombe, England: “On the 22nd of June, Jonathan Fiddle went out of tune.”

Anna Hopewell’s grave in Enosburg Falls, Vermont: “Here lies the body of our Anna — Done to death by a banana. It wasn’t the fruit that laid her low, but the skin of the thing that made her go.”

On a grave from the 1880s in Nantucket, Massachusetts: “Under the sod and under the trees, lies the body of Jonathan Pease. He is not here, there’s only a pod. Pease shelled out and went to God.”

In a cemetery in England: “Remember man, as you walk by, as you are now, so once was I. Remember this and follow me.” To which someone replied by writing on the tombstone: “To follow you I’ll not consent until I know which way you went.”

Sign in a Tombstone, Arizona cemetery: “Here lies Lester Moore, killed by a .44. No Les, no Moore.”

Candelabras of the desert — Most of the yucca in southeast New Mexico did not bloom this summer because of the drought. Those just had dry pods, like those seen in the foreground above, left over from last year. As we traveled past open prairies, it was easy to see which areas had been grazed by cattle because the yuccas in those fields were left with dry branches sticking up above the yucca but no remaining seed-filled pods, which cattle gobble up like candy.

Continuation of A Bonney Ballad by Jan Girand

So … who was our Henry McCarty, William H. Bonney, “The Kid?”

Where did he come from, who was his ma, why did he do what he did?

Of his latter years (alas, so few), we know his story well

for many, including Pat Garrett, his stories loved to tell.

His antics, shoot-outs, hot pursuits are documented well

in books, in movies and in songs, stretched out so they would sell.

And sell they did, even in England, for folks there love a tale —

of strife, romance and intrigue as they quaff their brew and ale.

***

… to be continued …

Pictured below is the Santiago Bonney Ditch as it appears today, more than 150 years after it was dug in southeast New Mexico, by James Bonney in 1845.

The origins and genealogy of Billy “The Kid” Bonney and his early life remain a mystery. So too is the mystery of why he, in the latter portion of his short life, adopted the name Bonney. Most published historians think that: a.) He began life in New York as Henry McCarty; b.) He changed his name to William Henry Antrim to match his stepfather’s after his mother’s marriage in Santa Fe in 1873; and c.) He adopted the name William H. or Billy Bonney only in the last years of his life. Historians don’t know from where he acquired or why he adopted the Bonney name. Most admit they are uncertain, but think he might have been born in a New York City Irish slum in 1859. Both the place and the date of his birth could well be incorrect.

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine