It all started around 1850 when some cowboys found gold in the nearby Jicarilla Mountains. That set off an interest in placer mining that continues today. Thirty years after that initial find, three prospectors, one of whom was hiding from the law, found gold in the Baxter Mountain, and perfected a claim that became the North Homestake Mine. George Baxter, for whom the mountain was named, George Wilson and Jack Winters were the prospectors. George Wilson had escaped from the El Paso jail and felt the need to keep moving. So rather than settle down and mine, he sold out to Winters for $40, a pony and a bottle of whisky. The boom was on. A few hundred feet down the gulch, another claim was staked that became the Old Abe mine. Abe Whitman staked the claim but never worked it very hard. He eventually sold it to William Watson for $1. In 1890, Watson found one of the richest gold veins in the United States. The Old Abe mine claimed the deepest shaft in the world and had a drift of more than 7,600 feet. When the mine closed 25 years later, it has produced about $3,000,000 worth of gold.

The population of White Oaks grew to between 2,500 and 4,000 souls. In the 1880s and 1890s, it was the busiest town in the Territory. White Oaks boasted four newspapers, a general store, three churches, a planing mill, two hotels, a bank, and of course casinos and bars.

The Watt Hoyle residence, built in 1880, stands today on the west side of town, looking down on the few remaining buildings. Hoyle had the home built, for his fiancée, by Gumm Bros. for about $40,000. However, Hoyle never married and he left White Oaks around 1900. The house has been restored and is a residence today.

About 1890, the Hewitt Building was constructed to house the bank, a general store and lawyer’s offices upstairs. In the 1940s, the Lazy H6 Ranch bought the bank building and began moving it to the ranch headquarters. Over the next 20 years, the blocks from the bank building became part of a home.

The old school building, which was still operating for eight students in 1936, remains near the middle of town. It has been restored and is now a museum. Across the wash, it is east of the main part of town. The general store has been restored and is now an operating business.

By 1955, there were only eight families left in White Oaks. The post office closed and it looked bleak for the town. However, during the town’s heyday, it had 2,500 residents and it boasted some of the state’s most prominent citizens. New Mexico’s congressman, H. B. Fergusson, was one. He wrote the Fergusson Act, which gave millions of acres of federal lands to the state for its schools. Another was the first Governor under statehood, W. C. McDonald. Emerson Haugh, the author of “Hearts Desire,” used his fellow White Oaks townspeople for characters in his book. The first U.S. Marshall for New Mexico was Andrew Hudspeth, who later went to the New Mexico Supreme Court. By the time of his death, in 1948, he owned most of White Oaks. Susan McSween Barber moved there after surviving the Lincoln County War. White Oaks may have been Billy the Kid’s downfall. According to lore, a person sleeping in the hay in the livery stable there overheard Billy Bonney tell a friend that he was going to Ft. Sumner. That conversation was passed on by the witness to Deputy Sheriff John Poe and Sheriff Pat Garrett, who waited for Billy at Pete Maxwell’s house at Ft. Sumner; the rest of that story is recorded history.

New Mexico, a state full of memorable ghost towns, is experienced in the booms and busts of mining and oil and gas. People are always waiting for the next treasure find that will lead to a boom.

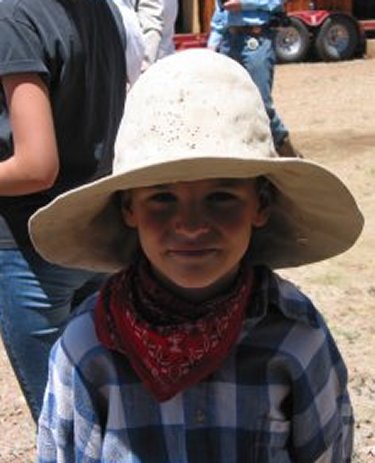

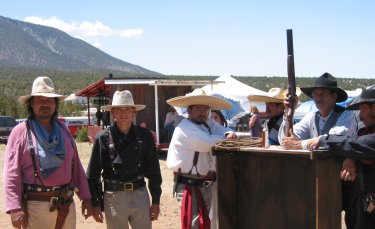

Our sojourn on Saturday, June 1, was to attend the White Oaks Miners’ Day, an annual occasion. The ghost town, with a small permanent population of mostly artists, was that day overrun with tourists, old-time miners, wild-west desperados and their fancy ladies. There were encampments, enactments — including an Old West Shoot-Out by the Paso del Norte Pistoleros, and Madam Varnish performed by resident Ruth Birdsong — and many things to do, observe and eat. White Oaks holds several scheduled events each year.

Returning from White Oaks back towards Carrizozo, the traveler is awed by the odd mountain formations that form the backdrop, as if made by an artist’s broad diagonal brush strokes. Those are the Vera Cruz Mountain to the left, and portions of the Sierra Blanca directly ahead and to the right as we drive towards Carrizozo. Soon after leaving Carrizozo, we — returning through the Sierra Blanca Mountains on our return to Roswell — began to climb into the mountains and in short time, found ourselves in the small high community of Capitan, birthplace of the original Smokey Bear, symbol of forest fire prevention.

During a 17,000 acre fire in the Capitan Mountains in 1950, a tiny badly singed Black Bear cub was rescued and flown to Washington DC to become the official live Smokey Bear. Ever since then, he — depicted as a cub or an adult bear in posters, billboards and other forms — has told generations of school children and adults: “Only YOU can prevent fire fires.”

With dangerous forest fires and wildfires raging all across New Mexico, southern Colorado and other states this tinderbox-dry summer, Capitan and its symbolic Smokey Bear are important reminders to not be careless with matches and cigarettes. So too is the Wildland Firefighters Museum in Capitan, that features equipment from the past, and a few pieces from the present. This museum represents all pertinent agencies: the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), the New Mexico Forest Service (State FS), Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). In the museum, the only one of its kind in the nation, are photos and informative displays of firefighters working on actual fires. Admission is free and education about wildfire prevention is the museum’s mission.

Capitan, in Lincoln County, at an elevation of 6,350 between the Capitan and Sacramento Mountains, has a current population of about 2,000. It has several annual activities. One of those is the Smokey Bear Stampede on July 4 that includes a fun run, parade, barbeque, western dance and rodeo. The third week in July of each year is the Ranchers Camp Meeting at nearby Nogal Lake. The first weekend in August, Capitan, along with nearby Old Lincoln Town, celebrates Old Lincoln Days, that includes a re-enactment of Billy the Kid’s Escape, a parade, a fiddlers’ contest, and many other portrayals and activities. The third week in December, Capitan, along with White Oaks, holds open house to visitors.

Returning home, we pass Old Lincoln Town and travel through the scenic Hondo Valley. To review prior published articles on these, click on Archives and go to Byways pages of previous issues.

Candelabras of the desert — Most of the yucca in southeast New Mexico did not bloom this summer because of the drought. Those just had dry pods, like those seen in the foreground above, left over from last year. As we traveled past open prairies, it was easy to see which areas had been grazed by cattle because the yuccas in those fields were left with dry branches sticking up above the yucca but no remaining pods, which cattle gobble up like candy.

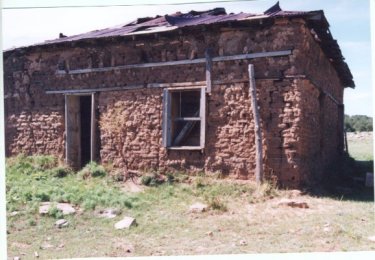

Pictured above is an old adobe Bonney abode, built in the 1800s, as it now looks at the beginning of the new millennium. It is on private property in northeastern New Mexico, and was the residence of the son of a blue-eyed Englishman named James Bonney. Could there be a family connection between James and Billy? Some say that is a possibility.

Where did he come from, who was his ma, why did he do what he did?

Of his latter years (alas, so few), we know his story well

for many, including Pat Garrett, his stories loved to tell.

His antics, shoot-outs, hot pursuits are documented well

in books, in movies and in songs, stretched out so they would sell.

And sell they did, even in England, for folks there love a tale —

of strife, romance and intrigue as they quaff their brew and ale.

***

… to be continued …

====================================

The origins and genealogy of Billy “The Kid” Bonney and his early life remain a mystery. So too is the mystery of why he, in the latter portion of his short life, adopted the name Bonney. Most published historians think that: a.) He began life in New York as Henry McCarty; b.) He changed his name to William Henry Antrim to match his stepfather’s after his mother’s marriage in Santa Fe in 1873; and c.) He adopted the name William H. or Billy Bonney only in the last years of his life. Historians don’t know from where he acquired or why he adopted the Bonney name. Most admit they are uncertain, but think he might have been born in a New York City Irish slum in 1859. Both the place and the date of his birth could well be incorrect.

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine