In the March issue, we took a daytrip together, beginning from Roswell, through the Hondo Valley and turned left at the fork, ending up in Ruidoso before returning home. If you wish to review it, click on Archives, Issue 2.

On this issue’s daytrip, we will turn right at the highway fork and head to Lincoln and Ft. Stanton.

The weather is comfortably warm; it is a great day for adventure. Grab your camera; I’ve got mine.

This is a good photo opportunity day because the sky is almost back to its clear blue and the wind is calm. Just days earlier, neither was the case. For much of a week, the sky — even in Roswell — was hazy with smoke because strong winds added to the dangerously dry timber conditions spreading a fire in the mountainous Mayhill area, destroying at least 20 structures there, including homes. Only a day or two before our trip, the fire was finally brought under control and put out.

We leave town heading west on Highway 70-380. As the new four-lane highway continues to progress westward, we pass some highway construction. Ahead of us we vaguely see the pale blue teepee-shaped Capitan Mountain. We see the mountain better on most days when the sky is clear without lingering smoke. Later today, we will see the Capitan much closer and from a different perspective; it will then not at all resemble a teepee.

The picturesque Hondo Valley is rich in history; it has seen both placid and turbulent times. It’s most turbulent days were during the Lincoln County Wars, when the residents’ loyalties were sharply divided between two factions. It is surprising to learn that, 125 years later, the loyalties of some residents of Lincoln and Chaves Counties are still divided. Those include descendents of some of those who played leading roles during the War. Some think the faction of Lawrence. G. Murphy and James Joseph “J.J.” Dolan was on the side of the law; others think the cause of John Henry Tunstall and Alexander McSween was the right one. More likely, both sides were wrong because principals of both were confrontational, greedy and stubborn and they practiced “mob law.” Those who legally dealt out the law of that time, in Lincoln and its surrounding area as well as in Santa Fe, were no better.

Even if I could, I will not attempt to here give an overview of that very complex conflict. Over the past 100-plus years, many articles and books have been written and are still being written about the War and Billy the Kid. It is a popular subject even with many far from southeastern New Mexico. If you want to know more about this interesting subject, many books are available (in print) for purchase or to check out of your local library. Some adhere closer to facts than others.

One (no longer in print) that did not stay close to fact, according to modern historians, is a book written by Sheriff Patrick Garrett, ghost-written by Asmun Upson: An Authentic Life of Billy the Kid. That was the first published book about Billy, and it began the international launch of his legend. If you’ve inherited this book or find it in a garage sale, especially a first edition, grab and hold onto it; it is a very valuable antiquarian item.

Some of my history books on the subject — that stay with the known facts and are enhanced with many photographs — include Merchants Guns and Money, the Story of Lincoln County and its Wars, by John P. Wilson, Billy the Kid, A Short and Violent Life, by Robert M. Utley, and two copies autographed to me by Englishman Frederick Nolan: The West of Billy the Kid and The Lincoln County War. Those written by Nolan are my favorite of the histories. Then there is another, written as a novel rather than a history book, by local author, Elizabeth Fackler: Billy the Kid, the Legend of El Chivato. I found that one the most enjoyable to read. All of these and others can be found in bookstores or libraries. I consider Fackler (Sinkovich) a friend, and have met Nolan (when he autographed my books at the SENM Historical Museum a few years ago) and know several people who call him friend.

Leaving Roswell, we climb out of the Pecos Valley and the terrain becomes more undulating. The further west we travel, the more distinct become what I call the rolling “hills of Peter Hurd.” Traveling throughout the Hondo Valley, travelers pass by what had been small Hispanic settlements established during the days of the Lincoln County Wars along the Rio Bonito, the Rio Ruidoso and the Rio Hondo. Besides the remaining small settlements, we pass several large ranches.

As we drop down into the Hondo Valley, the highway goes into a steep, winding descent. We pass Riverside, a wide spot on the highway with only two buildings — a cafe, and a small store or service station that are, more often than not, vacant. Today, the cafe is closed but the little store shows signs of activity.

Tinnie Mercantile, photo taken in late February before the trees turned green.

We again pass picturesque Tinnie Mercantile, a restaurant nestled among giant cottonwoods. For years, this large white rambling building with its red roofs and tower, has been a favorite subject of artists and photographers.

Across from Tinnie Mercantile is the old Tinnie cemetery. We stop to take pictures.

Just past Tinnie Mercantile and within the small roadside community of Tinnie is a road that turns right, north, and climbs into the hills to Arabela. On our photo-opportunity trip today, we take that road, Highway NM-368, and are glad we did.

Road to Arabela with Capitan mountain, that no longer resembles a single teepee, in the background.

We travel about 17 miles, climbing into the foothills of the southeast end of the Capitans, before the road dead-ends just beyond Arabela. This small rural community was originally called Los Palos (the Sticks), and had a post office from 1901 to 1928. Its last postmaster was a man named Pacheco. We take photos of a large lovely old home and the remains of the Arabela school house. (Note: A reader from California, whose family has lived in the Hondo area for generations, has advised the Roswell WebMag that the original name of Arabela was Las Palas (the Shovels) rather than Los Palos. We appreciate the correction, Ernesto.)

House at Arabela

At the dead-end, we turn around and return to Tinnie where the road meets Highway 70-380. Beside this Arabela turnoff is a small store and cafe that has a reputation for great barbeque smoked brisket sandwiches and ribs. It is lunch time and we are hungry. The cafe lives up to its reputation; after our enjoyable lunch, we continue our journey.

Old Lincoln Cemetery

Today at the highway Y at Hondo, where travelers must choose between going to Ruidoso or Lincoln, we chose the highway that turns right to Lincoln. On the outskirts of Lincoln, we stop to take photos at the old Lincoln cemetery. Entering Lincoln, at mile marker 98, we again stop, this time to photograph the historic Ellis Store, built in 1876, which is now a bed and breakfast on well-manicured grounds with an expanse of lawn edged with flowering hedges. The somewhat confusing historic roadside marker reads: “Ellis & Sons’ Store. About 1876, the Ellis’ fleeing commotion in Colfax Co. started a store in Lincoln. … Support McSween, later J W Laws made a TB sanitorium, an early effort to use Valley’s climate.”

Ellis Bed and Breakfast at Lincoln

The small town of Lincoln has been preserved and restored back to the way it was in the days of the Lincoln County Wars. Nestled between the mountainsides in a long narrow river valley, the town’s historic storefronts are neatly lined up on either side of the highway. We pass Casa de Patron and the Montano Store on our left, the Anderson-Freeman Visitors’ Center and Museum set back off the highway to our right. Also on our right is the “Torreon, a stone fortification erected by early Hispanic settlers used as a defensive structure to fight Apaches and used by Murphy-Dolan faction during the Lincoln County War.” Across from the Torreon is Iglesia de San Juan Bautista, the small Catholic church build in 1887. On our right is the Tunstall Museum, Dr. Wood’s House, an adobe ruin site, and the Wortley Hotel and Dining Room. Across the highway is the small Community Church, the old school house and the Murphy-Dolan Store that once served as the courthouse. It was from an upstairs room of that building that William H. “Billy the Kid” Bonney made his famous “final escape,” killing Bob Olinger.

The Old Lincoln County Courthouse, from where Billy the Kid Bonney made his last, and most famous, escape — which is reenacted every year in Lincoln.

I have fond memories of camping out with friends in the grassy meadow behind the Iglesia de San Juan Bautista during an Old Lincoln Days event several years ago. The tent encampment was a Cavalry soldiers’ re-enactment. That night, as I lay under the stars in the crisp and fragrant night air, the surrounding mountainsides magnified and echoed the sounds of whinnying horses and, from a neighboring encampment, the rat-a-tat-tat of drums and the mournful tunes of a fife. The ambience transported me back to the era of the nation’s Civil War, and the civil war in Lincoln County.

This year, the New Mexico Heritage Preservation Week is celebrated May 10 through May 19 in Lincoln and the surrounding area. According to their brochure, during those nine days in Lincoln will be “live music, chuckwagon cookin’ and cowboy storytellin’; arts & crafts demos; 19th century infantry camp; walking tours; talks about the Lincoln County War characters; BLM walking tours and lectures; Apache traditions, culture and stories; Hispanic forum & panel discussion; three cultures tour; carriage rides; Fiber Fest; and spinning & weaving demos at La Placita.” The brochure suggests that you “walk the same streets as ‘Billy’ with historian and author, Drew Gomber.” Most of the events are free but some have limited seating so reservations are encouraged by calling (505)-653-4025.

After we drive through Lincoln, stopping to explore and take photos, we continue to drive west for several miles. A few miles beyond Lincoln is, on our left or south, the road to Fort Stanton; we take it.

Humming around at the Fort Stanton Post Office

Fort Stanton also celebrates New Mexico Heritage Preservation Week, this year from May 10 through May 19. Their brochure says they will offer “good family festivities (including) live military re-enactors, storytellers, Apache dancers, Hispanic settlers, good food and good fun” Sunday, May 19 from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. (We returned to Fort Stanton on May 19 and they indeed had a wonderful celebration, with hundreds of people in attendance. For that one-day event, the entire Fort Stanton complex was open to the public.)

The portion of Fort Stanton normally open to the public is staffed by volunteers of Fort Stanton, Inc. in partnership with the Roswell field office of the Bureau of Land Management, the Lincoln County Historical Society, the Mescalero Apache Nation and the Ruidoso Valley Chamber of Commerce.

The Fort Stanton Museum, above, and the Post Office are the only buildings normally open to the public. The majority of Fort Stanton is being used as a drug rehabilitation center. Therefore, photo-taking opportunities are limited and then only under strict supervision.

A preserved portion of Fort Stanton, but usually off-limits to the general public.

Fort Stanton Inc. is a non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of this historically-valuable property for posterity. Their brochure reads: “Fort Stanton has led a long, interesting and diverse life. From its establishment during the Indian wars and involvement in the Civil War and the Lincoln County War, it served as a military stronghold. Although decommissioned near the end of the 19th century, it continued to function as a federal hospital, then as a state hospital. Today, Fort Stanton is about to change again. This time the cultural and historical heritage will be restored forever!”

Church at Fort Stanton, which is presently within that portion off limit to the public.

Their brochure also reads: “Fort Stanton (was) established May 1855 to control Apaches in the area. (It was) occupied by Confederate forces in August 1861. (It was) reoccupied by Kit Carson and five companies of New Mexico volunteers in October 1862. Fort Stanton brought stability to the area and encouraged settlement of Lincoln County. (It) was a major control factor during the Lincoln County War. (It) was home to Buffalo soldiers (who) helped control Apache bands led by Victorio and Geronimo in the 1880s.

“Fort Stanton is associated with several legendary figures, including Billy the Kid, who was incarcerated in the guardhouse; Territorial Governor Lew Wallace who is reputed to have written parts of his novel Ben Hur while relaxing in the quiet of the isolated post; and John J. ‘Black Jack’ Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces in WWI, who served two tours of duty at the fort in 1887 and 1889.”

The brochure goes on to tell visitors: “Fort Stanton was officially abandoned by the Army in 1896, turned into a Merchant Marine tuberculosis hospital by the Public Health Department in 1899; served (more than) 10,000 Merchant Marines with tuberculosis; was an internment camp for the crew of a German Luxury Liner that was scuttled off the coast of Cuba in 1939; Fort Stanton was transferred to the state of New Mexico in 1953; was entered into the State Register of Historic Places in 1973; and entered the State’s Most Endangered Buildings list in 1999.”

The U.S. Public Health Service Hospital Cemetery, established 1899, and Merchant Marine Cemetery at Fort Stanton. Here are also buried, separately on the far west end of the cemetery, four Germans from the crew of the German Luxury Liner that was scuttled off the coast of Cuba in 1939, and subsequently interned at Fort Stanton.

Fort Stanton Inc. strongly encourages, and seeks, support efforts from the public to preserve and restore this only surviving fort in New Mexico.

After our wonderful sojourn in Lincoln and at Fort Stanton, we head for home.

CONTINUING TO EXPLORE THE ORIGINS OF “BILLY THE KID” BONNEY

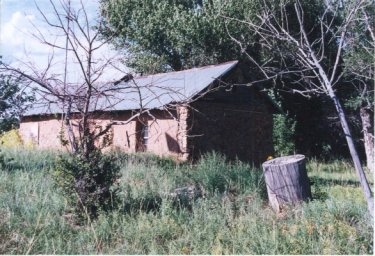

Pictured above is an old adobe Bonney abode, built in the 1800s, as it now looks at the beginning of the new millennium. It is on private property in northeastern New Mexico, and was the residence of the son of a blue-eyed Englishman named James Bonney. Could there be a family connection between James and Billy? Some say that is a possibility.

Continuation of A Bonney Ballad by Jan Girand

***

To cause more consternation, some time after that,

to his aliases added he another, and not a simple “Mac.”

As if he hadn’t then enough, he took a whole new name

this newest one was Bonney, and his life was changed again.

Have you heard of that one? From whom or where was it taken?

It had to come from somewhere; was his family line forsaken?

He was Irish, they’d said? And Bonnie Prince Charlie was Scot,

so that’s not it … hmm … and a “bonnie wee lad” he was not.

“It is just a name!” philosophers and poets will tell you.

The name is not the thing, they say, it is the deeds you do.

Well! It’s certainly true that Henry/William/Billy the Kid

McCarty/Antrim/Bonney did not outlive the deeds he did.

And daring-do deeds he did, they say in books, movies and songs.

His multiple lives and legends through mighty tall tales live on.

Twenty-one killings say they, one for each year of his life.

His life, especially if shorter, was certainly filled with strife,

but too many killings were credited him, extolling a violent life.

On the 1880 census, said Billy, the year before he died,

he was born in Missouri and his years were twenty-five.

But historian, Herman Weisner, said Billy was nineteen instead

when Sheriff Pat Garrett shot him, and there declared him dead

in Pete Maxwell’s Ft. Sumner adobe that July night of ’81.

Billy died in that darkened bedroom, a tragic end for Catherine’s son.

Twenty-one killings intended just wasn’t the way that it was —

four, maybe five all together; just one of those for sure was his.

And that was Ollinger in Lincoln who’d bulled the poor lad so

and made false accusations. Our Billy had to go

for if he hung around there long, a hanging would be his fate.

He had to make fast his getaway before it was too late.

When Billy made a run for it, armed Ollinger stood in his way

so Billy had to shoot him to make good his getaway.

So … who was our Henry McCarty, William H. Bonney, “The Kid?”

Where did he come from, who was his ma, why did he do what he did?

Of his latter years (alas, so few), we know his story well

for many, including Pat Garrett, his stories loved to tell.

His antics, shoot-outs, hot pursuits are documented well

in books, in movies and in songs, stretched out so they would sell.

And sell they did, even in England, for folks there love a tale —

of strife, romance and intrigue as they quaff their brew and ale.

***

… to be continued …

(To see earlier portions of this poem, click the Archives button and go to Byway pages of the previous issues.)

Pictured below is the Santiago Bonney Ditch as it appears today, more than 150 years after it was dug in southeast New Mexico, by James Bonney in 1845.

Santiago Bonney Ditch

The origins and genealogy of Billy “The Kid” Bonney and his early life remain a mystery. So too is the mystery of why he, in the latter portion of his short life, adopted the name Bonney. Most published historians think that: a.) He began life in New York as Henry McCarty; b.) He changed his name to William Henry Antrim to match his stepfather’s after his mother’s marriage in Santa Fe in 1873; and c.) He adopted the name William H. or Billy Bonney only in the last years of his life. Historians don’t know from where he acquired or why he adopted the Bonney name. Most admit they are uncertain, but think he might have been born in a New York City Irish slum in 1859. Both the place and the date of his birth could well be incorrect.

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine