The origins and genealogy of Billy “The Kid” Bonney and his early life remain a mystery. So too is the mystery of why he, in the latter portion of his short life, adopted the name Bonney. Most published historians believe that: a.) He began life in New York as Henry McCarty; b.) He changed his name to William Henry Antrim to match his stepfather’s after his mother’s marriage in Santa Fe in 1873; and c.) He adopted the name William H. or Billy Bonney only in the last few years of his life. Historians don’t seem to know from where he acquired or why he adopted the Bonney name. Most admit they are uncertain, but think he might have been born in a New York City Irish slum in 1859. Both the place and the date of his birth could be incorrect.

My mama was a wee child then, her memories were vague, you see.

Ramon Bonney, her great-half-uncle, was lonesome for company

so often he rode his donkey to her parents’ ranch for chats

and meals and recognition and a rub by their sociable cat.

He was nearly blind by then and hungered for more company

than that of his decrepit old mules and his faded memories.

***

He spoke only in Spanish, English was not his tongue

so his nephew’s wife, his hostess, tried to teach him some.

In exchange he taught her Spanish that she, a German, thought

was important in New Mexico where Spanish was used to talk.

***

My mama’s mama, Emma, smiled and cooked for him huge meals

so he’d go home replenished, his spirit and stomach filled.

Back then the children thought of him as just a silly old guy;

they were bored by his retold tales, scared of his cataract-scarred eyes.

They did not listen to his tales, thought they’d better ones of their own,

and they laughed when his mules hid from him behind scrawny pinons.

***

“Uncle Bonney” they called him, even my grandparents Emma and Dan.

An old man he was then, but he once was a virile young man

who had fathered many children. Still — he chose not a domestic life.

Husbandry wasn’t for him; he was the nomadic type.

He lit out for adventure and excitement is what he got

as he roamed the hills and canyons and mountain lions he shot.

He had a wagon caravan, and he took it far and wide

to St. Louie, Santa Fe, Denver, far beyond the Great Divide.

He peddled pots and pans then, bolts of calico, tatted lace

while he pushed great herds of cattle as he roamed about the place.

(To be continued in the next issue.)

Rwm

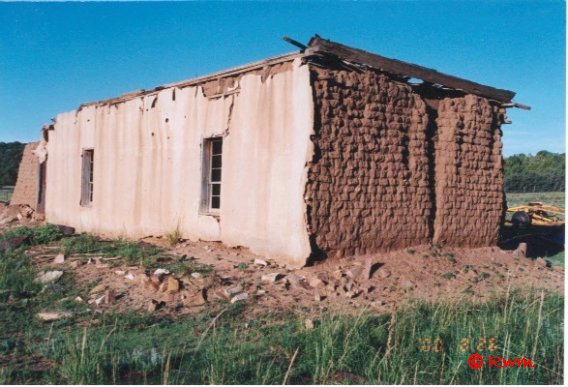

Ramon was a contemporary of Billy the Kid Bonney and he went to Las Vegas, NM to visit Billy when he learned he was incarcerated there, to see if they were related. Herman Weisner, a historian, whose practice it was to do his own research by interviewing old-timers and looking for original documents and court records, believed there was a possibility the two Bonneys, Ramon and Billy, were related. (Therefore, also the original occupant of the above pictured dwelling.)

Ramon was a contemporary of Billy the Kid Bonney and he went to Las Vegas, NM to visit Billy when he learned he was incarcerated there, to see if they were related. Herman Weisner, a historian, whose practice it was to do his own research by interviewing old-timers and looking for original documents and court records, believed there was a possibility the two Bonneys, Ramon and Billy, were related. (Therefore, also the original occupant of the above pictured dwelling.)

Pictured at left is an irrigation ditch, as it looks at the beginning of this millennium, that was built by James Bonney in northeastern New Mexico about 1845. It is still called the Bonney Ditch. James Bonney, an Englishman, was the father of Ramon Bonney as well as others from whom descended many New Mexico Bonneys.

THE HONDO VALLEY

You and I begin our daytrip heading west on Highway 70-380 out of Roswell on a good four-lane highway. The temperature is about 60 but drops somewhat by the time we reach the end of our journey, the mountain resort of Ruidoso. The turquoise sky has a few white wisps of clouds.

A song said, “On a clear day you can see forever.” Today is a clear day. Ahead of us is the pointed top of Capitan peaking above the horizon a bit to the right, its blue blending into the paler blue of the sky. Although seen from Roswell as one peak, Capitan is an oblong group of mountains, running from west to east, and its eastern-most end of it is what we see. It seems the largest but that is because it is the closest of the visible mountains. From the outskirts of Roswell on the plains, we can also see whether there is snow on Sierra Blanca, 70 miles away. That is the larger but more distant formation on the horizon almost directly in front of us. Today, in mid-February, Sierra Blanca lives up to its name, White Mountain.

The land is a softly undulating terrain as we begin climbing out of the Pecos Valley. To our right, at the Chaves-Lincoln County line some 30 miles beyond Roswell, is an abandoned Atlas Missile silo in which some enterprising entrepreneur greeted the New Millennium, along with a fireworks display, by sending messages and paid advertisements by laser beam into outer space.

In 1878, Lincoln County was much larger than it is today, then almost a quarter of what is now the state of New Mexico. It included Lea, Eddy, Chaves and portions of other counties, as well as Lincoln County. It was broken into smaller parts when the vast county’s east side became more populated and those residents complained that the county seat was too far away to travel to it.

The Hondo Valley, like Lincoln County and the town of Lincoln, was the setting for the turbulent times of the Lincoln County Wars. Those who chronicle the last years of Billy The Kid Bonney’s life write of the many areas and settlements along the valley’s Rio Bonito, the Rio Ruidoso and the Rio Hondo.

Rio Ruidoso, which originates in the Sierra Blanca, and Rio Bonito, which originates a distance to the north also in the Sierra Blanca mountain range, join together at a junction to become the Rio Hondo that continues east until it joins the Pecos River. Plazas — small settlements of mostly Hispanic people — began to spring up along those rivers by the late 1850s. In general, they were sometimes called las placitas de los rio bonitos — the places of the pretty rivers. The first recorded settlement was La Placita, later called Lincoln town, existing during New Mexico’s brief encounter with the Civil War.

Highway construction, with reduced speed limits, begins about 15 miles west of Roswell to extend the four-lane to Riverside. New Mexico representatives in the 2002 Legislature voted to double fines for speeding in construction areas, and speed limits are enforced here; we watch for signs.

About where the construction ends, the terrain begins to change into the larger rolling hills made famous by the art of Peter Hurd. These hills remind me of a giant’s uplifted knees loosely draped with a thread-bare chenille bedspread. Instead of counting sheep, the restless giant’s hands had plucked out the dark green chenille tufts from the beige spread until few tufts remained. The simile doesn’t quite work, because whoever heard of a giant with many knees? Still, the image sticks with me.

Here, the sparse evergreens (the dark green “chenille tufts”) are short and rounded pinons (pronounced PEEN yons), and juniper — which, in New Mexico, is often miss-called cedar.

The highway goes into a steep winding descent as we drop into the Hondo Valley. We pass by what had been the entrance to Robert O. Anderson’s Circle Diamond Ranch hidden behind trees and a high earthen berm. (For much more information about Robert O, see the article about him on Industry page.)

The highway passes through the long narrow valley with larger rolling hills that later become mountains on either side.

Riverside is little more than a wide place on the roadside with a cafe and gas station that, over the years, is often vacant. Today, an “Open” sign hangs in the cafe’s window.

The highway is now a winding two-lane that passes between rolling hills. Occasionally, it turns into three or four lanes to allow vehicles to pass slower traffic. On the left side, the valley sometimes widens to allow space for fruit orchards or irrigated fields plowed for planting, an occasional pond and a few cattle or horses grazing in grassy meadows. On our right, the hills come down to meet the highway without shoulder room. In places where the hills were cutaway for the highway to pass through, colorful layers of amarillo (yellow) and naranjo (the color of red-orange terracotta) strata are exposed.

The narrow winding highway is made for a driver’s enjoyment, yet rarely is a sports car seen. Tractor-trailers, motor-homes, SUVs, pickups and four-door sedans are the norm. During our valley drive, going and coming, we note license tags from Kansas, Arkansas, Ohio, California, Michigan, Arizona, Florida and Illinois. However, half of the vehicles are an equal mix from New Mexico and Texas.

Giant cottonwoods that must have been in the valley for centuries spread wide their winter-bared arms in the meadows, and tall slender poplars, with arms stretched straight up, march in soldier-like formation beside lanes and acequias (irrigation ditches).

We pass a few large ranches and small settlements that wind along beside the Rio Hondo. Hondo Valley is known for its apple orchards. Throughout the valley, we see roadside stands, both flimsy and substantial ones — for selling of many varieties of apples by the bushel, cherries and cherry cider, colorful chile ristras, honey, Portales peanuts, pumpkins and other produce. A few also sell things like pottery and hand-made quilts. Today, only the year-around substantial ones are open, for this is not the season for fresh orchard and farm produce. We don’t stop. In late summer and early fall, all the roadside stands will be active mom and pop enterprises. We will return then to buy varieties of the best crisp and juicy fresh-picked apples, better than any found in grocery stores.

On our left — elevation 4,976 the sign says — we see an old Pratt Truss bridge. Vehicle traffic no longer traverses it. A newer bridge was built alongside it to accommodate road travelers heading south. The bridge was built in 1902 over the Pecos River and was later moved here where it now spans the sun-spangled Rio Hondo. The sign beside it says the bridge is the longest and oldest of its kind in New Mexico. I have heard that the old bridge in the Hondo Valley is to be carefully taken apart piece by piece and moved to and reassembled outside the Farm and Ranch Heritage Museum in Las Cruces for historical preservation and display. I believe this is that bridge.

We pass the bridge, set back only a short distance and clearly visible on the south side of the highway about five miles before we reach Tinnie. The terrain is still mostly Peter Hurd’s rolling hills that look like they are loosely draped with those plucked chenille spreads. Once the hills begin, they and later also the mountains, almost always meet the highway on the right. On the left, throughout the long narrow valley, the land sometimes gives way into meadows, fields, orchards or settlements, before the hillsides or mountainsides on both sides again close in against the highway.

We almost drive past Tinnie, but stop and park in front of Tinnie Mercantile, nearly hidden by large cottonwoods. It is all we see of the settlement except for the small Tinnie cemetery, with its whitewashed crosses, across the highway. History recorded the name and place, a general store and post office, in 1882.

The Tinnie Mercantile was the first of a number of historic buildings entrepreneur oilman and rancher Robert O. Anderson began buying in 1959 to restore and in which to establish restaurants of fine cuisine and fill with antiques from all over the world. (For more information about Robert O. Anderson, his many restaurants and vast ranches in New Mexico, see the article featuring him on the Industry page.)

It is morning and the restaurant is not yet open; otherwise, we would go inside to eat. We do, however, stop and get out of the car with our camera to get some great photos of the large picturesque white building, with its red roofs and steeple and rambling glassed-in extended dining area, that is so popular with artists and photographers.

Just past Tinnie is a road that climbs straight north to take travelers to the small settlement of Arabella that sits below the east end of Capitan mountain. A bit further north of Arabella is the alleged Jim Ragsdale UFO crash site, a thought that seems incongruous for this historic setting.

Beside the highway, near the Arabella turnoff, is a quaint Protestant church, white with a green roof. We drive on a short distance to where Highway 70-380 comes to a Y. Near this highway Y, three rivers also join. Coming from the west, Rio Bonito and Rio Ruidoso join to become the Rio Hondo.

Highway 380 and Rio Bonito angle northwest to old Lincoln Town, Capitan and Carrizozo. Highway 70 heads southwest, alongside Rio Ruidoso, to Ruidoso, Alamogordo, Las Cruces and onward to El Paso, Texas. Today, we take the left fork of the junction, Highway 70.

Another time, when we can spend the entire day exploring and describing that area’s visual impact and rich history, we will take the right fork in the road, Highway 38, to visit nearby Lincoln Town, where the Lincoln County Wars originated and where Billy The Kid had his infamous shootout, and to Capitan, the mountain home of Smokey the Bear near the Lincoln National Forest.

The valley widens to the left to accommodate meadows and small settlements, including San Patricio. We turn off at mile marker 281 and take the steep road down into San Patricio. There is La Rinconada, the large adobe, with green roof, art gallery of Peter Hurd and Henriette Wyeth and their artistic family. The Wyeth family has produced, thus far, four generations of artists. Seven of them still reside in the Hondo Valley.

Peter Hurd was a cowboy from Roswell who loved to play polo. Local stories tell of how he, with charcoal, pastels and sketchpad, aimlessly wandered for days wherever his horse took him. One woman I know told how, when her mother was a young waitress at a Roswell truck-stop in the 1940s, a dusty cowboy smelling of horse sweat walked in and asked for breakfast. After he ate, he told the waitress he had no cash with him to pay for the meal. He gave her a sketch he made on the back of the menu as payment. She was poor and could not afford to pay for his meal out of her pocket, but she did. She did not know until much later who he was and the value of his sketch. By that time, it had been discarded.

Peter studied art for 10 years at Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania under the critical tutelage of the famous artist and classical book illustrator, N.C. Wyeth. Living with the multi- talented Wyeth family, he met and fell in love with his tutor’s eldest daughter, Henriette. They married in 1929 and, against the wishes of her Pennsylvania family, moved to Hurd’s beloved Hondo Valley in New Mexico where they lived and painted the remainder of their lives.

Henriette was as fine an artist as any of her famous family. She outlived Peter and continued to paint at the family home in the Hondo for many more years. I had the honor of meeting the gracious and fragile lady one day when she took tea in the gallery about a year prior to her death in 1997 at the age of 90. I was amazed to see her misshapen right hand, and to learn it had been that way since early childhood because of polio. With that hand, brush held between her first and second fingers, she created exquisite works of art, including portraits, beginning in her teen years.

In San Patricio beside the Hurd properties is Meigs’ Gallery, a rambling adobe compound known for years as Meigs’ Fort, which housed much of the art and antiques gathered by artist and collector John Meigs from all over the world. For me, a favorite part of the Meigs property is the hidden meadow with its overhanging canopy of gigantic cottonwoods. Meigs’ Gallery is now the Benedictine Spirituality Center.

We find other photographic opportunities in San Patricio, including three churches. One of these is the small white, with green roof and steeple, historic St. Patrick’s Catholic Church being restored by its parishioners. Its graveyard is directly in front of it.

We climb back up the steep hill and cautiously pull onto the highway, there’s little visibility here of oncoming traffic, to continue our daytrip. We pass more settlements. With our windows partially down, we enjoy the fragrant pinon and juniper wood-smoke rising from fireplace chimneys across the valley.

We pass several cruzitas beside the highway. These small white crosses, usually adorned with colorful wreaths, commemorate the places where loved ones died, usually in automobile accidents. They are common in New Mexico, especially in remote mountainous areas. Some such sites are old, and the memorials are continually cared for by subsequent generations of families.

These cruzitas are reminders of the many accidental deaths on this stretch of highway. Those accidents are the cause of an ongoing controversy. Many people, including politicians, want to change the highway, making all of it four-lane and straighter as it passes through the valley, to reduce the number of accidents. Valley property owners do not want their land and way of life altered.

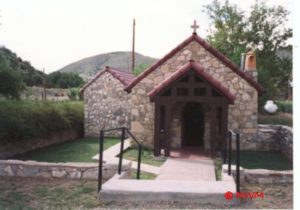

About half-way between San Patricio and Ruidoso Downs, is Glencoe. It is a small settlement established by the Coe family more than a century ago. Coe brothers Frank and George figured prominently in the history of Lincoln County Wars. On one side of the highway, we see the large red barn and apple orchard that had once belonged to the Coe family. On the other side of the highway, we see Glencoe’s little rock church that was established by the Coe family.

About half-way between San Patricio and Ruidoso Downs, is Glencoe. It is a small settlement established by the Coe family more than a century ago. Coe brothers Frank and George figured prominently in the history of Lincoln County Wars. On one side of the highway, we see the large red barn and apple orchard that had once belonged to the Coe family. On the other side of the highway, we see Glencoe’s little rock church that was established by the Coe family.

Before we reach the outskirts of Ruidoso Downs, we pass the vacant Fox Caves against the mountainside. There had once been dwellings within the cliffs. More recent enterprising souls added block buildings and corrals to capture tourist trade.

We begin to pass many roadside stands displaying large quantities of bears of all sizes carved from trunks of pines by talented chain-saw sculptors.

On our right, we pass the Billy the Kid gambling casino and the Hubbard Museum of the Horse. First time passersby are startled to see several beautiful, spirited horses, manes and tails flying, as they run across the small display park in front of the museum. These are actually marvelous life-like pieces of art in perpetually suspended animation.

We must come again when we can spend most of the day touring inside the Museum of the Horse, an adventure all by itself.

We pass the Ruidoso Downs Race Track that draws tens-of-thousands to New Mexico during the summer and early fall racing season. Then the valley highway traffic is dense and through-traffic at the outskirts of town sometimes comes to a standstill as crowds exit the race track. We are glad today is not a day of races.

We enter the village of Ruidoso situated mainly within the narrow valley between the two mountainsides. Where the now-four-lane highway traverses the length of the town, it becomes the community’s main street. A large portion of the village that draws tourists throughout the year is comprised of cabins, campsites, trailer parks, motels, restaurants and fast food places, outlets for hand-crafted furniture, art galleries, small shops with gifts and clothing, ski rental shops and stores that sell ski apparel.

Visitors park their vehicles and walk up and down the street to shop and sightsee and wander across the street with little regard for highway traffic. On this mild-weathered day, it seems strange to see people, in winter apparel and boots, carrying skis on their shoulders and hear the clink-clink of tire chains hitting the pavement as four-wheel SUVs pass by. But then, not so strange since Ski Apache is nearby and there is snow upon Sierra Blanca.

There are things that appeal to visitors here throughout the year. Instead of skiers, in summer the village caters to campers, fishermen, and horseback riders. Year around, shopping and gambling is in season at Ruidoso, as are tourists seeking glimpses of the old Wild West.

After buying a rustic bear with personality, we stop for a satisfying lunch before slowly heading back through the historic and picturesque Hondo Valley to Roswell.

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine