(Editor’s note: these two syndicated Jay Miller columns were published in many New Mexico community newspapers in November 2005. They are herewith republished in this webmag issue with Jay Miller’s permission.)

(Burial marker over the approximate area of the last resting place of Billy the Kid and his pals in Fort Sumner. Photo taken Sept. 2004 by roswellwebmagazine editor, Jan Girand)

BILLY RIDES AGAIN

by Jay Miller

Syndicated Columnist

SANTA FE–Here’s a quick look at the past year’s strange events in the afterlife of New Mexico’s most famous personality: Billy the Kid.

Following the September 2004 victory by the Village of Fort Sumner that secured the dismissal of the suit to dig up Billy, the action quieted for awhile.

November elections were in the offing and the Lincoln County sheriff’s office was due for a change. Sheriff Tom Sullivan couldn’t run again, so a new sheriff would take over. And Deputy Steve Sederwall, who also is mayor of Capitan, tried running for the county commission but lost.

Sheriff Gary Graves, in DeBaca County, the third sheriff investigating the Kid’s demise, was safely in the middle of a four-year term, but a year later, he was recalled by voters in the most bizarre election in New Mexico history.

Not only was it the first time a sheriff had been recalled, it was the first time an election was scheduled, stopped and then restarted. Graves’ Texas attorney, Bill Robbins, protested the election to the state’s Court of Appeals and got it stopped.

But on advice of the district attorney, the election was held as scheduled and though Robins sought an 11th-hour contempt charge against the county clerk and an injunction to interrupt the voting, the Appeals Court did not issue either. Graves was recalled by a vote of 576 to 150.

It also was discovered that Graves’ attorney, Bill Robins, is not licensed to practice in New Mexico. That raises the question of whether he followed the correct procedures to represent Graves in this case.

Robins also represented the three sheriffs in the Fort Sumner grave-digging case and was the one who spoke for dead Billy, requesting that he and his mother be exhumed.

No matter what happens, the Court of Appeals is sure to persist and the Billy the Kid case will continue to get more outlandish.

Meanwhile, new Lincoln County Sheriff Rick Virden has deputized both Sullivan and Sederwall, who are back on the case. Last May, they obtained permission from the state of Arizona to dig up the remains of Billy the Kid pretender, John Miller, from state-owned Arizona Pioneer Home Cemetery.

That exhumation remained a secret until last month, when an article by Julie Carter in the Ruidoso News revealed the dig had taken place on May 21 and disclosed that Miller had buck teeth and a bullet wound similar to the person Pat Garrett shot. The article featured a picture of Sederwall holding the skull–minus the buck teeth.

The reason for the delay in the release of the information remains a mystery. Miller’s bones are at a lab in Texas awaiting DNA comparisons with blood from a carpenter’s bench on which Billy’s body may have been placed.

Meanwhile, rumors circulate that more of Miller’s bones were removed from his grave than are necessary for an autopsy. Anyone interested in learning more of the John Miller story can read Whatever Happened to Billy the Kid, distributed by Sunstone Press, in Santa Fe.

Somewhat forgotten in all the strange twists of this story is that the three sheriffs agreed to submit a report to Gov. Richardson following their investigation. That report is to include a recommendation as to whether he should issue a pardon to Billy.

Gov. Lew Wallace had promised Billy a pardon in return for his testimony in a murder case during the Lincoln County War. Billy upheld his end but Wallace didn’t and would never answer Billy’s letters from jail.

Why didn’t Wallace answer? Why didn’t he uphold his end of the bargain? Many theories have been advanced over the years.

Most likely is that the political corruption that extended through the judicial and law enforcement arms of government were too much for an appointed territorial governor from the outside to overcome.

Also worth a look is the question of what good or harm a pardon might do at this point.

(Headstone of Catherine Antrim, mother of Billy Bonney, in Silver City, NM. Her first name is misspelled on her stone. Photo taken in 2005 by Jim Littleton of Silver City.)

CONTINUING BILLY THE KID SAGA

by Jay Miller

Syndicated Columnist

SANTA FE–Billy the Kid continues to haunt the courthouses and cemeteries of the southwest.

For over two years, Billy has been the subject of an official criminal investigation, court suits and grave-digging efforts, one of which was successful.

And amidst all this, accusations have flown back and forth, two communities have had to spend money they could ill afford, a principal character lost an election and another was recalled.

I have recently had a book published containing over 30 columns recounting the saga of what appeared to begin as an attempt to promote tourism in Billy the Kid country. It’s called Billy the Kid Rides Again: Digging for the Truth. In the following paragraphs, you’ll learn the reasons behind the title.

The tale begins with an investigation by three sheriffs from the area, along with Gov. Richardson, to find the facts about how Billy shot two Lincoln County deputy sheriffs to make his daring 1881 escape.

They also wanted to determine the truthfulness of claims that Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett shot someone else so that Billy could escape and lead a long life in Texas or Arizona.

And the investigation was to look into the pardon promised to Billy by then-Gov. Lew Wallace in return for his testimony in a murder case during the Lincoln County War. Gov. Richardson wanted to know whether he should issue that pardon.

That’s a pretty big field to cover, but the governor planned to appoint people to represent all parties, who would then conduct field hearings in Billy the Kid Country and attract international media attention.

So far, so good. But then DNA entered the picture and the sheriffs and governor wanted to dig up Billy in Fort Sumner and his mother in Silver City and compare their DNAs.

But the governor’s Office of the Medical Investigator pointed out that the precise locations of both graves was difficult to pinpoint.

Billy’s cemetery had been flooded by the Pecos, washing away grave markers, which were later replaced from memory. The cemetery in which Billy’s mother was buried was purchased and the bodies moved to a different location. And even if the bodies could be located, 120-year-old bones don’t yield useable DNA.

So, without the approval of the medical investigator, it was necessary for the sheriffs and governor to go to court to secure approval to dig up the bodies.

Silver City and Fort Sumner both owned the cemeteries in which the bodies were buried. And both communities had misgivings, not the least of which were concerns of descendents that the remains of their loved ones in nearby graves would be disturbed.

And when the sheriffs went to court, they made it part of an official criminal investigation. That’s when an earnest effort at promoting tourism turned into a Keystone Kops circus, complete with three rings.

In one ring was Billy’s escape from the Lincoln County Courthouse. In another was Pat Garrett’s shooting of Billy. And in the third ring was Gov. Wallace’s failure to pardon Billy.

It’s difficult to get a criminal case out of that. Who was the criminal? Billy the Kid was co-petitioner, asking that he and his mother be dug up. Pat Garrett is the champion of the Lincoln County Sheriff’s Department, whose picture appears on its shoulder patch.

When the going got tough, Richardson appointed Texas attorney Bill Robins to represent Billy. Never mind that the law doesn’t give governors the right to appoint lawyers for individuals. It also doesn’t allow dead men to speak in court. But Billy did.

It didn’t help, however. Neither court gave permission to dig. But forensic scientist, Dr. Henry Lee, of Court TV fame, volunteered to find DNA somewhere and the sheriffs easily managed to dig up Billy pretender John Miller in Arizona.

So get ready to hear many more revelations of questionable acts and misdeeds. It ain’t over yet, because Billy refuses to ride into the sunset.

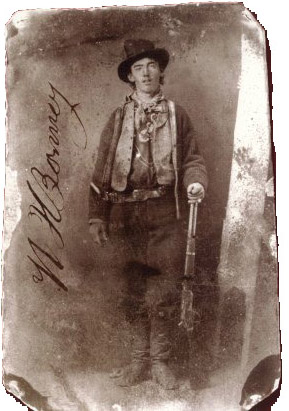

Photo copied from the original tintype for a postcard (with Billy’s signature superimposed on it). The original had, for several years, been on loan to the Lincoln County Heritage Trust from the Upham family, who owns it. Historians believe this 2-inch by 3-inch ferrotype was taken at Fort Sumner end of 1879 or early 1880, one of four identical copies. This Upham tintype, now in very poor condition, is the only remaining authenticated image of the boy called Billy the Kid Bonney.

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine