Vic’s essays usually have morals embedded, and always show the goodness and nobility of his subjects as well as that of the author.

This set of essays took place more than 60 years ago. “I expect they were all over before 1940,” said Vic.

AUNT ELSIE

by Victor J. Reeves

My aunt, Elsie May Reeves, youngest of seven children, was born in Valley View, Texas in 1899. She was seven when the family moved to The Ranch in El Paso County. As I hear it, she was never much of a cowgirl, nor wanted to be. She preferred books and the arts to hard saddles and sweaty horses. When she helped at all on roundups and branding, it was as a sulky brat kid, which usually got her sent to the house, which was just what she wanted!

Elsie was the only one of the seven children who actually graduated from college, although each was given the option. Sorta. College, business college, trade school, or “get a job and git started on your life!” Grandpa’s attitude was that college was a waste of time and money — HIS time and money — for anyone, especially a girl.

Elsie made teaching her profession, and art her specialization. She taught in several schools in the El Paso system, ending her career as head of the Art Department at El Paso High School. She also took care of her mother — our Grandma — for the last 10 or so years of her life. She never married.

I’m sure you are familiar with the Old Mill in Ruidoso, the one with the big waterwheel. Over the years (more than a hundred of them), that old mill has been used in many ways. It has stood idle for years at a time, only to be renovated and put back to work. The summer of 1938 was a downtime for the mill, and Elsie decided she wanted to put a skating rink in it. She rented the building for the summer, and proceeded to do just that.

She was the proprietor, and I was her only employee. The pay was good: Board and Room, and Free Skating. It sure beat ranch work in the hot sun.

The building was a terrible place to try to skate. It was, and is, far too narrow for comfortable turns, and the floor was rough. But it was Ruidoso’s first attempt at giving the kids a place to skate. For the want of a better place, they came.

My sister and three of her cousins, all in the 10-to-14-year bracket, came up for a week at a time, one or two at a time, all summer. We all enjoyed the adventure immensely. Even the steady diet of canned mixed vegetables, Spam and peanut-butter was fine with us. After all, we got to sleep right up under the tin roof. In a thunderstorm, that’s a fun place to be.

Elsie was a good organizer, motivator and business person, but a skater she was not. We all wheedled and teased her daily and nearly ran her crazy, but no dice. One afternoon, when there was nobody there but us, we got her up on a pair of skates by insisting the floor was not very hard, and she probably wouldn’t get a splinter.

She made a few loops with me holding onto her, then she said she could do it alone. She did. About 10 feet. Then her feet went out from under her, and she sat down pretty hard. Everything was very quiet. She sat there, with her skirt spread out all around her, and just looked at us. She didn’t cry but she didn’t laugh either. We all started toward her to help her up and she screamed at us. “Get away from me! Don’t touch me! All of you get out of here. I’ll get up when I’m good and ready. Get these damn skates off my feet and then get lost, all of you!” So we did. And she did.

None of us ever said a word about her embarrassment. And I never will!

Another summer, Elsie wanted to go to California. She offered me the chance to go with her and help drive. I wasn’t hard to persuade, of course.

She had an old Studabaker Dictator. It was a fine car, (not that old in years) but obsolete. We planned to cross the Desert at night to avoid the worst of the heat. We left El Paso late on a Saturday afternoon, and drove without incident to some place in Arizona. It was about 2 a.m. and we were weary. We saw this brilliant neon sign on a tourist camp (the word “motel” hadn’t been invented yet). The sign said “refrigerated air;” neither of us had ever experienced that. Elsie said, “What the heck?” She was paying. What, me argue?

We slept like two logs, probably snoring like two buzz-saws, until about 10 a.m. Wow, Sunday morning, not very hot yet, and somewhere, not TOO many miles away, must surely be some breakfast. Yeah. Right.

I turned the ignition key. Oh yes, that Studabaker was the first car to have the starter hooked up through the switch! The sound that starter made was just one long “Rooooooooooooooooo” instead of “Roo roo roo roo Zoom!” as it should have sounded. Uh oh. I was only 15, but my Dad had taught me what THAT sound usually meant. Timing gear. Oh no… I took the distributor cap off, and asked Aunt Elsie to try the starter while I watched the rotor. It was not turning. Boys and girls, we were in one deep pile. Sunday morning, in the middle of Noplace, with a car they didn’t even make parts for anymore. Couldn’t be much worse …. could it?

Across the road there was a scruffy, flyspecked little gas station run by a dried-up prune of a man. Maybe he had a phone. If so, I would call my other aunt in El Paso. Somebody would have to drive 25 miles out to the ranch and tell my dad. If he could get a timing gear on Monday, put it on a bus addressed to Cactus Corners or whatever the name of that place was, then I could put it in on Tuesday. Dad had insisted I bring along quite a complete set of tools. Maybe we could be on our way with less than three days’ delay. Hope-a hope-a hope-a.

Just as I was about to drop the first quarter, the little man said, “What model is that Studabaker?”

I’m afraid I was slightly rude. No, smart-mouth kid that I was, I was VERY rude. I said, in the most disgusted voice I could muster, “It’s a ’34 Dictator. WHY?”

He calmly said, “Just hold on a minute.” After about 30 seconds of rooting around under his counter, he came up with a fiber gear. It was furry with dust, but obviously brand-new. He said, “I think this will fit.”

Speaking conservatively, I was flabbergasted! Actually, I was dumbfounded. With awe and some fear, I asked him how much it would cost. “Five dollars,” he said. FIVE DOLLARS! It would have cost us at least fifty to get it from El Paso, two days later! Elsie paid for the gear, thanked the man, and I ran across that road to get started on the job.

It took me a couple hours to take things off, out of the way and get down to the gear. About 10 minutes was enough to put the gear in (the sweet old man had checked my timing marks) and I got everything back together in record time.

We cranked her up, heard that wonderful “Roo roo roo Zoom!” and were loading up by 4 p.m.

We filled up with gas, thanked that nice man and WENT although we hadn’t even had breakfast.

I learned, as I continue to learn to this very day, not to judge a book by its cover, a business by its front door or a man by the number of wrinkles in his face.

Yet another time, another summer, that immortal (?) Studabaker and Elsie started out for California. By that time, two or three of the girl cousins were older, old enough to help drive, both Elsie and Stoody had experience, so off they went.

Driving at night, for the obvious reason, some were asleep and one was driving; we never did find out who, or what happened. Maybe a blowout, maybe heavy eyelids, who knows? Anyway, the driver lost control. The car darted across the road, over the lip of a very deep canyon — and stopped.

It had snagged on a gnarly old stump, jutting out of the side of the cliff, and the rear bumper hovered shakily just level with the pavement. After they realized they weren’t all dead, they began to turn their brains back on. Elsie cautioned them to not move suddenly, but one at a time to open the back doors and try to crawl back up over the rear end of the car and onto the road. They did.

Each one thought she would fall off, or the car would suddenly fall and let them all crash to the bottom. But none of that happened. Every one of them got back up safely, and they even opened the trunk and got out most of their luggage and possessions!

After a couple hours, a tow truck arrived, and the two men on board began to ponder how they were going to pull that heavy monster back up, vertically, and over the shoulder onto the road. Before they actually hooked onto it, the problem solved itself.

The car squealed, the stump popped, and down she went to the bottom. She’s probably still down there.

The ladies rode a bus the rest of the way, and while in California, Elsie bought her next — and last — car. It was a Pontiac, much younger than its new owner.

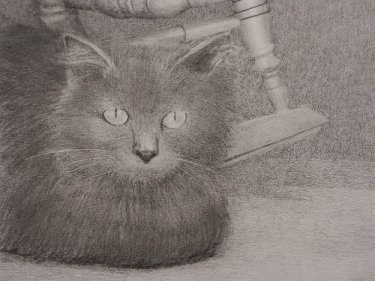

Portrait of “Victoria’s Cat”

Below is an essay submitted by a Roswell Web Magazine subscriber who resides in Danville, California

TABBY TREE JUMPER

Victoria A. Lorrekovich

Mournful meowing rushed through my kitchen window as I was having my morning tea. The screeching sent a chill up my spine so I went outside to investigate. I knew it couldn’t be any of our cats because they were all in-door-only cats. After much searching, I couldn’t find a feline although I could still hear the distraught mewing. I stepped back into the house and grabbed my binoculars. Peering through the magnified lenses, I could see a brown tabby in our pine tree, about 40 feet up. I panicked. It wasn’t a neighbor’s cat, but one of our own. I had no idea how Anya had escaped, nor why she climbed a pine tree so frightfully high.

I called her name. I rattled a food dish. I even offered her a halibut steak that was supposed to be part of Monday night’s dinner. She seemed paralyzed with fear. She had never climbed up a tree before, let alone down a tree. The hours crawled by agonizingly slowly.

My daughter, Ari, arrived home from school and was informed of her cat’s predicament. Because of the intense bond between Ari and Anya, I thought that Ari might be able to talk her down, but Anya’a anxiety refused to release her. After shedding tears of frustration, I broke down and called the fire department.

When I hung up, I assured both Ari and Anya that help was on the way. Soon, a bright red fire truck graced our court. I had never been so happy to see anyone in my life. However, the three firefighters who approached us acted as though they had someplace better to be. I explained the situation. The oldest of the three treated me like I was a hysterical housewife.

They surveyed the stately evergreen and told me that they couldn’t get their ladder close enough. They also made it clear that they weren’t going to climb the tree. “We don’t risk our lives for cats,” said the captain.

The rookie said, “Don’t worry Ma’am, we’ve never seen a cat skeleton in a tree before,” which elicited laughter from the other two.

I wanted to show them my children’s books depicting the sweet and brave firefighters who rescued children’s cats from trees. After they left, I was seriously thinking about not contributing a donation to the firefighters’ ball next year.

Poor Anya spent the night in the tree, with no food or water. The next morning, Ari’s bowl of cereal was soaked with milk as well as her teardrops. I promised her that by hook or by crook, Anya would be down before she got home from school. I told her that I’d climb the tree myself, if we couldn’t find anyone else to do it. My husband shot me a look that suggested this wasn’t a good idea.

I called six veterinarians in our area for advice. All told me to call the fire department. I then called Animal Services. Again, I was told to call the fire department. I guess we had all read the same children’s books. My husband and I brainstormed ideas…Who could climb our tree and emancipate our cat?

A tree service! I called at least twelve tree services before finding a man willing to rescue our run-away feline. It would cost $150.00. I told him I didn’t care how much it cost. My husband flinched.

Within thirty minutes of calling, a tall, lanky man with weather-beaten skin knocked on our door. Pete looked like an ad for the Marlboro man. He strapped on leg spikes and a leather belt and recounted his past rescue missions.

Pete explained that there were three categories of tree climbers: sitters, greeters, and runners. “The sitters stay put. They wait for their savior. The greeters make the climber’s job easier because they actually walk toward the rescuer. The runners are the worst because they bolt, usually higher up the tree.”

We’d get a discount if Anya was a greeter.

Pete shinnied up the tree like a monkey. Dangling from his belt were a rope and soft cloth bag that Anya would ride down in. As Pete reached our little fugitive, Anya climbed upward. “Oh man, she’s a runner,” Pete panted. Sweat dripped from his brow as he climbed higher. The pine was nearly 80 feet tall. As they neared the top, the tree began swaying dangerously back and forth. I wasn’t sure that the treetop could hold both a cat and a man six feet tall. My husband rubbed my back. His fingers were icy with foreboding. I loved Anya but I didn’t want to be responsible for risking a man’s life. Perhaps the firefighters had a point.

When Anya and Pete were as high as they could go, Pete tied himself to the tree. I was holding my breath.

“I’m reaching out to her now… Okay, I’ve got her,” Pete announced. Then a flash of fur hurled through the air. “Oh my God,” Pete shrieked, “She jumped.”

We saw tree branches breaking Anya’s fall at first, but then she fell the last 30 feet, clear of branches. She looked like a flying squirrel. She landed on her feet, dazed but alert. I carefully scooped her up and kissed her little black nose. Our poor cat-guy felt so bad, he told us we didn’t owe him a thing. We compromised on $75.00. Pete now had to add a new category to his list of kitty tree-climbers: jumpers.

We rushed Anya to the vet. She was bruised and suffered a hairline fracture of her collarbone, but otherwise was okay.

Ari was thrilled to find Anya resting on her bed when she got home from school. She wrote Pete a note of thanks. She then turned her attention to Anya, “Listen Miss, do you have any idea the worry you caused me? –and after all I’ve done for you. I cleaned your litter box, read you James Harriet stories at bedtime, and brushed your fur every day and this is how you repay me. As much as I love you, I’m afraid that I’m going to have to punish you. You may not watch TV for a whole week.” Anya did her best to look repentant as Ari scooped spoonfuls of halibut into Anya’s mouth. “Some times we-mothers have to be tough on you-children. It’s for your own good,” Ari explained.

Periodically we share goodies received by Email. This is one of those:

Louisiana Red Tape ( This is an actual case)

A New Orleans lawyer sought an FHA loan for a client. He was told the loan would be granted if he could prove satisfactory title to a parcel of property being offered as collateral. The title to the property dated back to 1803, which took the lawyer three months to track down. After

sending the information to the FHA, he received the following reply (actual letter):

“Upon review of your letter adjoining your client’s loan application, we note that the request is supported by an Abstract of Title. While we compliment the able manner in which you have prepared and presented an application, we must point out that you have only cleared title to the proposed collateral property back to 1803. Before final approval can be accorded, it will be necessary to clear title back to its origin.”

Annoyed, the lawyer responded as follows (actual letter): “Your letter regarding title in Case 189156 has been received. I note that you wish to have title extended further than in the years

covered by the present application. I was unaware that any educated person in this country, particularly those working in the property area, would not know that Louisiana was purchased

by the U. S. from France in 1803, the year of origin identified in our application. For the edification of uninformed FHA bureaucrats, the title to the land prior to U. S. ownership was

obtained from France, which had acquired it by Right of Conquest from Spain. The land came into possession of Spain by Right of Discovery made in the year 1492 by a sea Captain

named Christopher Columbus, who had been granted the privilege of seeking a new route to India by the reigning monarch, Isabella. The good Queen, being a pious woman and careful about titles, almost as much as the FHA, took the precaution of securing the blessing of the Pope before she sold her jewels to fund Columbus’ expedition. Now the Pope, as I’m sure

you know, is the emissary of Jesus Christ, the Son of God. And God, it is commonly accepted, created this world.

Therefore, I believe it is safe to presume that He also made that part of the world called Louisiana. He, therefore, would be the owner of origin. I hope to heavens you find His original claim to be satisfactory. Now, may we have our %#&* loan?”

They got it.

This Email was titled Generational Change:

“Hey, Dad,” one of my kids called out to me the other day. “What was your favorite fast food when you were growing up?”

“We didn’t have fast food when I was growing up,” I informed him. “All the food was slow.”

“C’mon, seriously. Where did you eat?”

“It was a place called ‘at home,'” I explained. “Grandma Stewart cooked every day and when Grandpa Stewart got home from work, we sat down together at the dining room table, and if I didn’t like what she put on my plate, I was allowed to sit there until I did like it.”

By this time, the kid was laughing so hard I was afraid he was going to suffer serious internal damage, so I didn’t tell him the part about how I had to have permission to leave the table.

My parents never drove me to soccer practice. That was mostly because we never had heard of soccer. But also because we didn’t have a car.

We didn’t have a television in our house until I was 11, but my grandparents had one before that. It was, of course, black and white, but they bought a piece of colored plastic to cover the screen. The top third was blue like the sky, and the bottom third was green like grass. The middle third was red. It was perfect for programs that had scenes of fire-trucks riding across someone’s lawn on a sunny day.

I never had a telephone in my room. The only phone in the house was in the living room and it was on a party line. Before you could dial, you had to listen and make sure some people you didn’t know weren’t already using the line.

Pizzas weren’t delivered to our home. But milk was.

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine