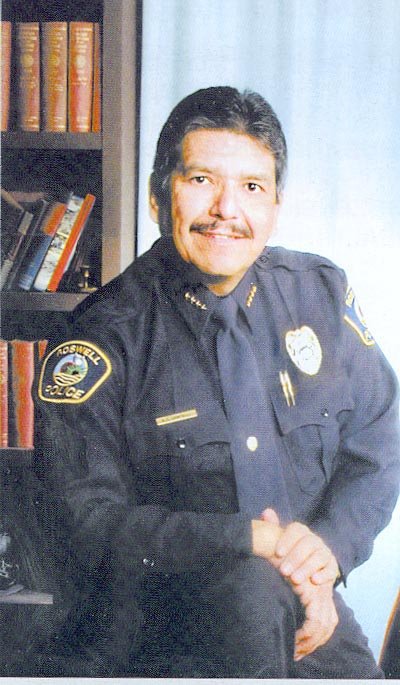

When Chief Richard Campbell came to Roswell as its new city police chief in 1996, he said, he found the department had a lot of room for development and growth. He feels he has brought about many needed changes in the ensuing 5 1/2 years that he has headed the department.

When he arrived, he said, he found serious problems within the community of violent crime and gang activities. “People were afraid to leave their homes after dark.” Now, 5 1/2 years later, overall crime is down 36%. The first year he was chief, the community had 11 homicides; last year, there were two. In 2001, all violent property crimes were down.

He said Roswell has become a healthier and safer place to live. Regardless, it frustrates him that people still complain and criticize. He said he wished those people would “look at the whole picture” and see the progress that has been made.

“Never never compromise your ethics,” he tells his officers.

He sets high standards for his department. “The men and women in this department are professional,” he said. “The officers are compassionate. The community needs to appreciate them. Crime is down in Roswell because of those law enforcement officers, because they care.”

“We have been fortunate,” he said. Thanks to “federal funds, this department is well equipped and has received good training — mental, physical, the techniques and the tools — necessary to successfully solve crimes.” He also credits the prosecutors with the district attorney’s office with that success.

Since he has been chief, he said the number of police shootings have been reduced. He credits that to the tools, training, law enforcement classes and the departments using alternatives to deadly force. Subsequently, lawsuits against the department are down. Campbell’s untiring efforts have brought to the Roswell Police Department varied innovative alternatives to deadly force. Those have been so successful that Campbell has offered to share their techniques with other law enforcement agencies and city police departments.

Until perhaps 10 years ago, the only defensive weapons an officer had were verbal, fists and handguns.

In-service training for officers includes options of using less-than-lethal weapons. The bean-bag shotgun and 10% OC pepper spray are some examples of less-than-lethal weapons.

Pepper-ball rifles, implemented last summer, are one of the newest types of weapons in the RPD’s arsenal. They can be fired from close range or as far away as 35 feet. The subject is temporarily immobilized; the balls are painful when they hit the victim, but cause no injury or illness requiring medical attention.

The air-rifles shoot hard marble-like balls filled with 5% OC pepper spray. The first reaction when shot is pain at the site of impact because of the ball’s velocity; as the victim recoils, he sucks in a deep breath of pepper spray released into the air upon the ball’s impact with his body. Where it hits is a bruise that goes away in a day or two; the pepper spray causes only temporary burning of the eyes, nose and skin. As an alternative if small children, elderly people or those with respiratory problems are in the immediate vicinity, the guns can also shoot inert or water-filled balls that release nothing into the air.

Crisis Intervention Training teaches street officers appropriate responses when dealing with violent people, including those with mental or emotional problems or under the effects of drugs or alcohol. The training includes knowledge of the law and a study of various types of psychological disorders and effects of psychotherapeutic drugs.

The Jail Diversion Program addresses a complex issue that involves many people and organizations. It involves the legal community, including District Judge Alvin Jones and, initially, Judge Chip Johnson. It requires a considerable amount of local support and a secure detox facility. The program provides for a number of treatment options for those with emotional and psychological disorders. It involves many community groups including legal professionals, care givers and mental health facilities. Like Crisis Intervention, it is usually the street officer who must first face and deal with the problem.

When situations makes it feasible, use of alternatives to deadly force are the trend of the future.

The high standards Campbell sets for his officers, which in turn gives them pride in their chief and department, and the innovative training, techniques and tools he has introduced have created a more professional law enforcement agency.

The police department constantly seeks recruits. The majority of the “applicants are rejected because the department’s standards — academic, physical and psychological — are tough. The average person can’t pass them,” Campbell said. He believes the citizens most critical of the police could not meet the standards RPD requires of its law enforcement officers.

Chief Campbell spent 21 years with the Albuquerque Police Department — beginning with uniform patrol, then as under-cover narcotics, as a homicide detective, with internal affairs, as area commander, and finally as deputy chief of patrol responsible for 700 employees. He retired from APD in 1993. He brought to the Roswell Police Department many years of law enforcement experience.

Both of his children, a son and a daughter, as well as a son-in-law are uniform police officers in Albuquerque. Perhaps the highest compliment a man could receive is having his children choose him as role-model when selecting their own professions.

(The following was written by Fleming as a talk he will give when he attends the annual conference of the Historical society of New Mexico in Las Cruces in April. He is a panelist who will speak about German prisoner-of-war-detainees during World War II, with emphasis on the farm work they did in the Roswell area. Rwm)

One of the largest detention centers in the U.S. for war prisoners during World War II was located between Roswell and Dexter. The name of the camp was “Roswell Prisoner of War Internment Camp” and its address was a rural route out of the Dexter Post Office. Local people usually called it “Orchard Park POW Camp” because it was situated in a community by that name. The location met the government’s requirements regarding maximum security, being isolated from sensitive military bases and industrial sites and separated from population centers.

Private construction companies that subcontracted the electrical, pluming and sewage systems built Camp Roswell, as officials and prisoners generally called it, in 1942. The Corps of Engineers was responsible for building the security fences and guarding the construction site.

The late Arthur Brosius, a Provost Sergeant with the 340th Military Police Escort Corps, was involved in getting the base operational, starting September 5, 1942. I interviewed Mr. Brosius about 25 years ago. Probably the definitive source on the history of the New Mexico camps is an article by Jake Spidle in the New Mexico Historical Review of April 1974. I have also interviewed Hans Rudolph Poethig of Roswell several times; he was one of the prisoners at Orchard Park. Other Roswell historians, such as Georgia B. Redfield and Ernestine Chesser Williams, have written on this subject.

Some 19 companies of guards were brought in to escort the prisoners in and out of camp. Brosius was at the camp the entire time it was in operation; he later was a well-known security chief at New Mexico Military Institute for many years.

The first 250 prisoners arrived on November 26, 1942; they were some of Rommel’s 8th Army Afrikakorps. The men got off the train about a mile-and-a-half from the camp and marched down the middle of the road to the camp under the watchful eyes of 35 guards with shotguns. These elite soldiers may have been Nazis; at least they were patriotic Germans who never lost their pride or bearing — a quality that was much admired by the American soldiers who guarded them. The number of prisoners at Camp Roswell reached 350 by the end of 1942.

Between July 15 and August 15, 1943, another 4,000 Germans arrived. Although there were many transfers and changes, the camp was pretty much filled to capacity after that until after the war ended. In the late summer of 1944, new prisoners arriving were old men and boys who had been captured in the campaign that started in Normandy on D-Day.

The 120-acre camp consisted of frame barracks buildings to house 4,800 prisoners in three compounds of 1,600 each. Four American physicians, two dentists, seven nurses and an optician staffed the modern, 250-bed hospital. Many prisoners assisted them. A large recreation area next to the compounds was used for exercise, tennis and especially soccer.

Two high fences enclosed the camp with barbed wire at the top. The fences were 15 feet apart, and there were about a dozen guard towers around the perimeter.

The buildings at Camp Roswell are said to have been solidly built and comfortable. The prisoners used native plants and rocks found on the scene to landscape and beautify the place. The camp strictly observed all of the terms of the Geneva Convention and received compliments from several international inspection agencies.

The prisoners made the best of their situation. Besides sports and games, many were active in various dramatic and musical shows. Camp Roswell always had an orchestra — sometimes two or three. They played everything from Mozart to “Pistol-Packin’ Mama.” Protestant church services — mainly Lutheran – and Catholic services were offered.

A large percentage of the prisoners enrolled in college-level courses taught by their own teachers or by correspondence from several universities. According to Art Brosius, the Germans, especially Rommel’s men, were always studying something. They had a library, and they published their own newspapers. Many of the prisoners were quite active in various arts and crafts projects and exhibits. One of the crafts they engaged in, according to Rudy Poethig, was making schnapps from oranges, orange juice and sugar they squirreled away. They had it hidden under the barracks floor in one-gallon pickle jars.

Few tried to escape, and none were very successful. At one point, guards discovered a tunnel; they filled it in with rocks and caved it in. A rancher near Artesia killed one escapee. The others were recaptured.

The original policy was simply to keep the prisoners in the camps. This policy was changed in 1943 because of severe labor shortage, especially in agriculture. Some prisoners were used by the military for roadwork and maintenance work.

One notable project in Roswell was placing rocks along the banks (“rip-rapping”) of North Spring River in Cahoon Park and elsewhere near downtown Roswell for erosion control. The prisoners used different colors of rocks to build a German Iron Cross emblem into the bank of the river. Local residents were upset about this, so that night they dumped a truckload of concrete on top of it. It remained hidden and was lost from memory for about 40 years. It is now recognized as an historical site in Roswell as part of the POW-MIA Park at Pennsylvania and West Ninth Street.

Farming out the prisoners to government entities seemed to work well, so a new policy was passed providing that prisoners could work as contract labor for private employers. On June 26, 1943, the Army announced that New Mexico POWs would be available for work on farms or elsewhere. Over 500 German prisoners were at work on farms in the Pecos Valley by the end of July.

Other areas wanted to use prisoners, too, so side-camps were established virtually all over the state. Camp Roswell had branches on the Hal Bogle farm in nearby Dexter, at Tweedy Farms, also close by, and in Artesia, Mayhill, Carlsbad, Portales, Clovis and elsewhere. The camps were usually small, such as the Bogle Farms camp with a capacity of 30 to 60 men. Other side-camps could handle up to 400.

Local farmers who lived close to the camp came early every morning with their trucks to pick up the Germans for farm work. Most of the agricultural work done by Camp Roswell prisoners was in the cotton patches. They did not particularly like this kind of work and were not as productive as local experienced children or women. Carl Clardy and Russell Smith, who uses as many as 250 prisoners around Roswell, stated that the Germans’ work was not satisfactory, but was “a whole lot better than nothing.” Spidle concludes that the Germans allowed they should not appear too eager to help the enemy, lest they incur the wrath of their own people and government after the war. Originally, farmers had to pay the prisoners the going wage for farm work, but they prevailed upon the government to allow a lower rate because of their limited productivity. According to Brosius, the pay amounted to about 80 cents a day.

Rudy Poethig, who worked as a linguist and dental assistant, decided he wanted to get out of camp so he asked for the job of cotton weigher. He soon discovered his mistake; he had to weigh the sacks of cotton picked by up to 60 men and empty the sacks into the trailer as many as two and three times a day.

Birdie Dee Eccles had to run her family farm at East Grand Plains, southeast of Roswell, while her husband worked as a highway engineer. Floyd Wagner, her farm tenant, had prisoners to do field work, and Mrs. Eccles had them to repair fences and buildings, do household work and perform other chores.

At the time of her experience with the prisoners, they brought raw ham and a chunk of bread for lunch. Presumably this was in the summer and fall of 1945 after V-E Day during the so-called “revenge” program of Eleanor Roosevelt, who maintained that the prisoners in America were treated too well. They were placed on a diet of 800 calories a day. Farmers realized that the Germans could not do farm labor on that diet, so they began to supplement their food supply while protesting to the Army about the short rations.

Each day, Mrs. Eccles collected the ham from the Germans on her farm and cooked it in a pressure cooker, then added onions, carrots and cabbage. One of the men was sent to the truck farm for fresh tomatoes and cucumbers. Mrs. Eccles put the food in a big bowl and gave each man a tin cup and spoon. They liked to pick out the chunks of food with their fingers, and then dip their bread in the broth. sometimes a watermelon would be cut up for the men, which was also enjoyed by the guard, Sgt. Brosius.

Like many others who employed prisoners, Mrs. Eccles got to know many of them quite well. They asked her a lot of questions about the USA and the Constitution. She gave them little books with the Constitution and the Gettysburg Address. They were curious about the right to keep and bear arms, separation of church and state, Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War over slavery.

Herbert Kohler, a German from Leipzig, worked in Mrs. Eccles’ house. Brosium told her it was all right as long as she did not get caught. When inspectors were coming in, Brosius would alert her, giving Kohler time to grab a hoe and run out into the garden and start chopping weeds.

According to Mrs. Eccles, a neighbor woman turned her in for coddling the prisoners. The FBI came to investigate. They told her she shouldn’t cook the ham for the prisoners, but they commended her for teaching them about America. They told the neighbor to get three other neighbors to sign the complaint and then contact them. That was the end of that.

Besides the truck garden and cotton patch, the prisoners on the Eccles farm worked in the fields of corn and alfalfa.

On one occasion, armed farmers began to congregate — which scared the wits out of the Germans. But it was only the start of a deer hunt in the mountains. Fred Nelson, who was another prominent farmer in the area, brought back a bear from the hunt. He cooked it over an open fire for the Germans at Thanksgiving. Mrs. Eccles said the prisoners liked the greasy bear meat, and she had an opportunity to teach them about Thanksgiving.

At one point, Italian prisoners were sent to replace the Germans. Mrs. Eccles aid, “They didn’t seem to know what to do about anything, and we had to give them up.” Farmers asked the Army not to bring any more Italians.

No more prisoners were brought to the U.S. after V-E Day. Art Brosius claimed that during the final months of Camp Roswell, some details of prisoners were allowed to go out to work on farms without guards. The prisoners knew the war was over and they would soon be going home, so they had no desire to escape or otherwise make trouble.

All of the side-camps were closed by the end of February 1946, and the main camp soon after. The Germans were taken to France and turned over to the French soldiers. Rudy Poethig says the French soldiers stole everything the Germans had.

Mrs. Eccles, Fred Nelson and several others kept up with some of the German prisoners after the war. There were visits both in New Mexico and Europe between the former POWs and their American employers. A few of the men of Camp Roswell came back to live in the area, most notably Rudy Poethig.

Most of the buildings were moved to Roswell Army Air Field and Eastern New Mexico University in Portales. Some were used for other purposes; at least two of the former POW barracks are still in use as residences in Roswell. The foundations of the camp buildings were destroyed about 1975, but the sewage treatment plant still stands.

In recent years, several pilgrimages of former prisoners and/or their descendants have come from Germany to visit the site. They are usually visibly moved by the experience but even more by the friendliness of the Roswell people who welcome them with open arms and show them a good time.

In 1935 when I was 13, I was boarding with a family friend, Beulah Tabor (“Aunt Beulah”) in El Paso. I was there to go through the final year of grade school and try to get up to speed for the Texas school system. I would be starting high school there next fall.

My folks were paying for my board, of course, but I had some little expenses for which I needed extra money. I got myself an afternoon paper route and that made it necessary for me to have a bike. Dad “loaned” me the money to buy a nice used one I had located.

Everything went well through the first semester. I was “acing” my classes, which proved that our little one-room school in New Mexico was not so far behind the Texas schools as we had been told — by Texans. In fact, it was not behind at all; it was ahead!

I had an ideal set-up there with Aunt Beulah, who was an excellent cook and fed me very well. She also sometimes let me drive her brand-new Plymouth.

But along in the spring, I was getting pretty homesick. Our ranch was only 25 miles away and that sounded closer and closer as the weeks wore on and my spring fever got worse and worse. One afternoon I couldn’t stand it any longer. I quit my paper route with no notice — which guaranteed I couldn’t get it back — and started out on Highway 54 toward Newman and home.

There was a medium-to-fierce sandstorm blowing from the southwest and the road ran straight north. This gave me a slight tailwind but a very strong side-wind. I had to lean as far to the left as I could to keep from being blown off the right edge of the road. I thought, “Oh boy, I’m glad I won’t have to ride back on this road, facing the wind.”

Even five miles under those conditions, with sand in my eyes, nose and mouth and down my collar, would have been pretty tough. But 25 miles was almost more than I could make. Many times I thought I would not make it. But the thought of Mom’s welcoming arms and a cold glass of milk and some cookies spurred me on.

At long last, with the (imagined) last ounce of my strength, I turned off the highway to ride the half-mile to the ranch. Now I was facing the wind at about 11 o’clock. I had to get off the bike and push it. The delicious thoughts of what lay ahead kept me going.

When I got to Mom’s kitchen door, I didn’t just barge in as I normally would have done. I even knocked. And knocked. She was sure slow getting there! When she finally did open the door, I could see right away that she was surprised, but not pleased, to see me. No smile. No open arms.

She looked me over and said, “Well, aren’t you a sorry looking thing!” and stood aside so I could enter. I got myself a glass of water. Mom said, “Well, now young man, what’s this all about?”

I was not going to cry. I WAS NOT. But I blubbered a little. “I just got homesick, Mom. I couldn’t stand it anymore. Aren’t you even glad to see me?”

“Yes, of course I’m glad to see you, but I don’t understand how you can be here at this time of day. What about your paper route? And what did you tell Aunt Beulah? I don’t think I’m going to like what you tell me, but try telling me anyway.”

So I did. I said I had quit my paper route. No, I hadn’t given any notice. Yes, the district manager was mad. He said, “Don’t come around here wanting your route back, because you don’t have a route here.” Gosh, I hadn’t even thought about Aunt Beulah.

“You didn’t think about her. No, it seems you didn’t think about anybody but yourself. What do you suppose she’s thinking right now? Isn’t this about the time she gets home from work and you get home from your route?”

“Yes’m.” My head was hanging and I was crying.

“I didn’t understand what you said,” she told me. I could hear her!

“She’s going to be frantic, Son. She won’t have any idea what could have happened to you. You know we don’t have telephones out here. We can’t call her to let her know that you’re at least all right. She can’t call us to see if we know anything about you. Somebody has to go and tell somebody. Now, go wash your face, go find your goggles and a cap, and I’ll fix you a glass of milk and a cookie or two. As soon as you finish, you’re going to get on that bike and head back to El Paso.”

“FACING THE WIND?”

“Facing the wind. You should have thought of that before you started out.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing, but the stern look on Mother’s face told me it was real. I made my cookies and milk last as long as I could, but I was hungry so that was not very long.

I reluctantly put on my skin-tight goggles (which would at least keep the sand out of my eyes), my aviator cap and jacket, and headed out the door.

Mom gave me a little pat but no hug, and said, “We’ll talk about this again. I’m sure your father will have something to say to you. We’ll probably see you this weekend. Now, you’d better get going.”

And she shut the door!

I had new strength from the cookies and milk and I was mad, hurt and scared. So the first mile or so went pretty well. I was throwing all my weight on each pedal as I pushed it down. Now I had to lean hard to the right.

I was going to have to keep right after it if I was going to get back to El Paso and Aunt Beulah’s before dark. And what was I going to say to her? Would she be mad like Mom? Or would she be just so relieved that she’d forget to scold me? I knew I had really messed up my whole world. I had definitely hurt some of the people I cared about most. Wow.

About five miles down the road, a familiar sound came up beside me. It was Dad’s pickup. He and Mom had come to give me more heck, I figured. But that wasn’t it. They stopped. Dad got out, came back and said, “Hi. Want a lift?” Whooboy, did I.

We put the bike in the back and I got in between my mom and my dad and I realized the world had not ended after all. Nothing was said all the way back to Aunt Beulah’s house. My parents went in with me and we found an almost hysterical woman. She was so glad to see me that she didn’t even seem mad. (I was the Prodigal Son, I guess.)

I had learned a valuable lesson about responsibility and maturity. I didn’t need a lecture.

(The setting of Vic’s memoir essay was the infamous Dust Bowl Days when large parts of Texas, Oklahoma and New Mexico were devastated by storms of blowing dirt and sand. Such conditions would “make or break” men’s spirits. Those who lived through times such as those were resilient. Their strengths of character are the foundations on which today’s communities were built. Rwm)

Roswell Web Magazine

Roswell Web Magazine